This January, the Smart Museum of Art welcomed two new exhibitions which pose important questions about identity and inclusion. The museum’s front gallery houses “Solidary & Solitary” from the Joyner/Giuffrida Collection. It consists of mostly abstract works created by artists of the African diaspora, and serves as a meditation on what it means to be a Black artist moving in solidarity with the race while maintaining a solitary identity. The rear gallery space features “Smart to the Core: Embodying the Self,” which presents provocative ways to contemplate the self-portrait.

Some of the artists in “Solidary & Solitary” relinquish the expectation placed upon them to create works solely depicting Black life, or those that engage some type of cause. Instead, artists like Norman Lewis and Sam Gilliam—who together have eighteen abstract paintings opening the show at the front of the gallery—are free from those constrictions. Nothing about their works speaks to their being Black or non-Black, and everything about them speaks resoundingly to their skill and mastery as artists.

Other pairings and solo artists included continue the show’s non-conformist theme, but the exhibition also includes works that can be considered a detour from this artistic stance, depending on how a viewer chooses to interpret the signs. Take “Stranger #68,” where Glenn Ligon spells out the opening words of the James Baldwin essay “Stranger in the Village” on a canvas of oil-stick, coal dust, and gesso. The essay chronicles Baldwin’s time spent living in a tiny Swiss village where none of the locals had ever seen a Black man. There’s also Ligon’s unlit neon, “One Black Day,” or the two specially commissioned installations by artists Amanda Williams and Bethany Collins, both of which nod astutely to the representation of Black suffering by speaking to the nation’s historical practices of redlining and lynching.

“Solidary & Solitary” inspires honest conversation about the realities of race relations past and present, in ways where even third grade classrooms can join the conversation. (Which they do regularly, as part of the Smart Museum’s work introducing elementary school students to the museum experience.) But a few steps further into the rear gallery space, inside the “Smart to the Core: Embodying the Self” exhibition, the door is opened for a more mature conversation spanning race and ethnicity; gender and sexuality; and the places where those identities intersect or collide.

“Smart to the Core: Embodying the Self” is the museum’s first exhibition curated by the Feitler Center for Academic Inquiry. The goal is to develop exhibits alongside the University of ChicagoUofC’s undergraduate Core curriculum, which aims to examine the human condition. A brief history of the curriculum is detailed in the booklet The (Un)Common Core, published in conjunction with the exhibition.

Through this exhibition, UofC undergraduates get to experience art along with theory and texts. A few of the undergrad texts are staged inside the exhibition at a seating area, with the invitation to peruse the pages or to personalize them by adding a piece of one’s self using pencils stationed nearby. Among the core curriculum titles available are Black Skin, White Masks by Black psychiatrist and philosopher Frantz Fanon, The Second Sex by feminist existentialist author Simone de Beauvoir, and The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx.

Each piece in “Embodying the Self” functions as an unsuspecting self-portrait, a large number of which dismantle the notion of binaries by sharply bending historical gender roles and examining notions of race and class. The exhibition eloquently invites patrons to get comfortable being uncomfortable.

Some works juxtapose Western notions of femininity with historical ideas of feminism, then allow room to consider whether femininity and the feminist can, or cannot, be the same thing. There’s “Self-Portrait/Nursing,” a print from the 2004 series “Self-Portraits & Dyke” by photographer Catherine Opie, which depicts a nursing mother. The piece is positioned adjacent to the naked figure and seemingly exposed breasts of Marilyn Monroe in Japanese appropriation artist Yasumasa Morimura’s folding fan, titled “Ambiguous Beauty/Aimai-no-bi.” In reality, Morimura himself dressed up, complete with wig and prosthetic implants, as Monroe.

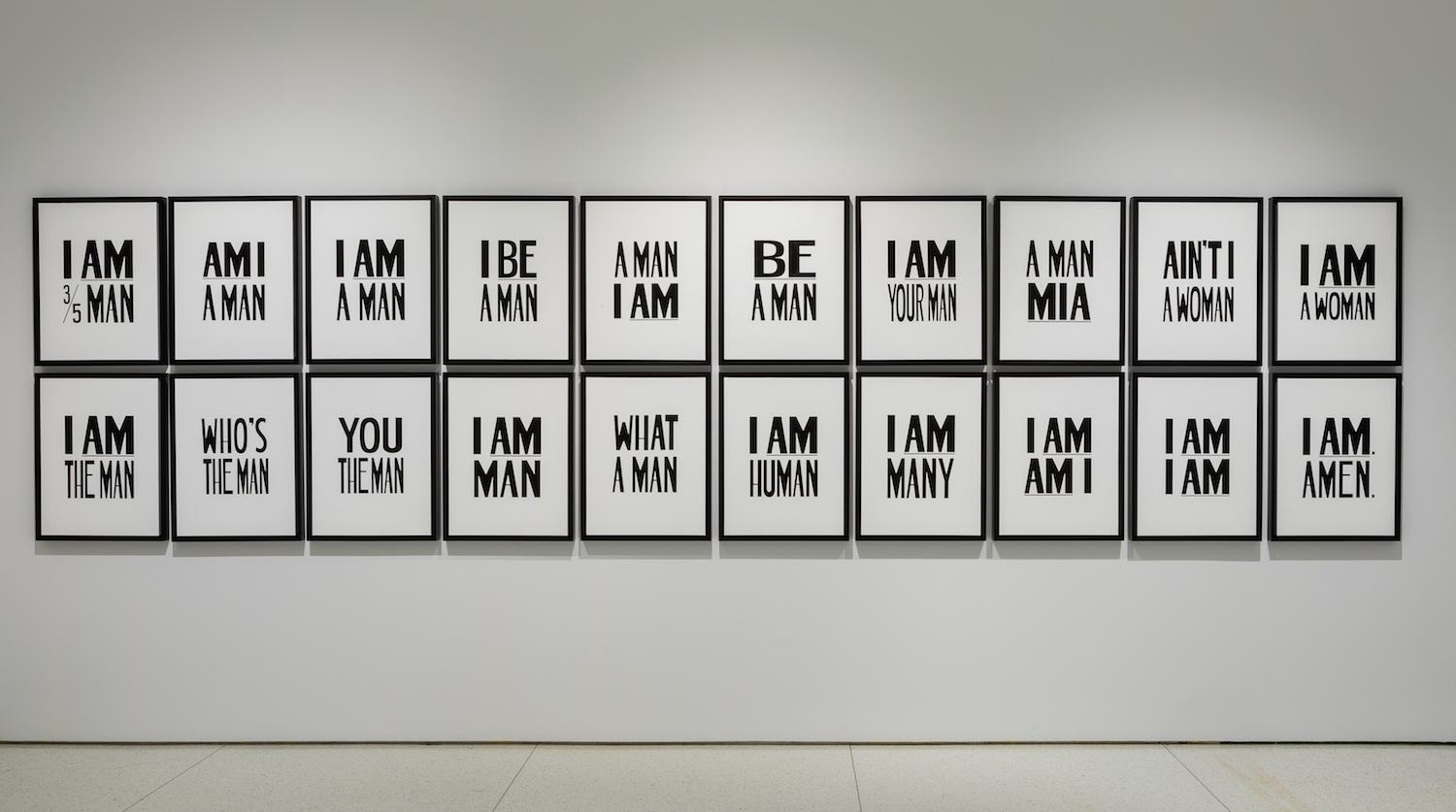

Conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas uses framed canvases in “I Am A Man” to deliver what might be twenty different statements on the identities of men and women collectively. Or it could be translated as one long, punctuated sentence chronicling Black racial identity throughout American history, going as far back as the Three-Fifth’s Compromise and ending with a lofty striving for the equity that is much talked about but still not fully realized.

Influential contemporary artist Carrie Mae Weems draws out questions on the female image, power, slave narratives and cultural misappropriation while leaving space for viewers to factor in their own likenesses. In “Some Said You Were the Spitting Image of Evil,” her chromogenic color print, the glass is so crystal clear each viewer’s own reflection meets their own gaze over the sandblasted text—the piece is a self-portrait for every person who views it. The print is one of thirty-three photos from the series “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried.” The photographs were originally taken by a nineteenth-century anthropologist in an attempt to validate a perceived inferiority of captured African peoples forced into American slavery, and were part of the Harvard University archives. In the 1990s the illustrious university threatened to sue Weems for using them in her series, but reconsidered when Weems agreed that it would be a good idea to have the conversation and all that it would entail inside of a courtroom. (Artnet News reports that a descendant of one of the slaves in the photos is currently suing Harvard for possession of the prints.)

Four digital works placed throughout the exhibition, from artists Frances Stark, Adrian Piper, Ma Quisha, and Howardena Doreen Pindell, add about an hour of video footage to the exhibition, examining gender roles, race, and the pressure to be perfect. Other works call into question ideas surrounding fatherhood, death, and Asian and indigenous narratives. Artist Ayana V. Jackson’s stunning pose in motion, “Labouring under the sign of the future,” makes space for Black femme beauty where it had been omitted in historical photographs, and is the visual image branding the exhibition.

“Smart to the Core: Embodying The Self” asks bold questions in large ways about the countless ingredients that comprise the self, and about how perceptions and expressions of the self change collectively and individually every moment. In “Solidary & Solitary,” the same expressions bypass the questions and go straight to the answers. Both exhibitions run through May 19, 2019, offering visitors a temporary opportunity to see pieces different from the Smart Museum’s permanent collection, equally as rich–if not more.

Smart Museum of Art galleries are located at 5550 South Greenwood Avenue, open Tuesdays through Sundays from 10am to 5pm and until 8pm on Thursdays. Admission is free.

Nicole Bond is the Weekly’s stage and screen editor and is on staff in the education department at Smart Museum of Art. She last wrote for the Weekly in September, reviewing the Court Theater production Radio Golf.