Evan Beverly doesn’t identify as a serious baseball fan. But as a lifelong South Sider and longtime bartender in Woodlawn bars where the game is always on, the thirty-six-year-old has an affinity for the White Sox. They’re part of his identity and that of his community, as a resident of the South Shore neighborhood. Positive memories of the team’s 2005 World Series victory, during which Beverly lived just a short walk to the ballpark away in nearby Bronzeville, reverberate to this day. That positivity, however, is lately becoming a distant memory.

“It’s disheartening to hear,” Beverly said about rumblings that the team could be on the move after the 2028 season. Emotionally, keeping the White Sox where they are should be a no-brainer. But with the team now asking for over a billion dollars in exchange for staying in Chicago, things aren’t quite so simple, especially with Beverly being well-attuned to the city’s perpetually dicey financial state. “If there are 300 people with the White Sox who utilize that stadium and 30,000 people on the streets right outside that stadium, who should you give that money to?”

Like many Sox fans, Beverly is disappointed in the state of the team beyond the recent news. Not even three years after winning their first division title since 2008, oddsmakers currently have them projected as the third-worst out of thirty MLB teams this season. In 2023, longtime chief executives Ken Williams and Rick Hahn were fired amid a 61-win, 101-loss season, the team’s third-worst in its 123 years of existence. Hope and good vibes, right now, are at a premium.

Wins and losses aside, that century-long history explains the deep connection between the team and the South Side. Founded in 1901, the franchise played their first ten seasons at South Side Park, located at the corner of 39th and Princeton and demolished in 1940. They moved to Comiskey Park in 1910—six years before the Cubs first occupied Wrigley Field—and have since played nearly 9,000 MLB games at 35th and Shields in the Armour Square neighborhood.

Now, in addition to the White Sox’ lackluster on-field showing, the future of that relationship is also in doubt. The team’s lease on the publicly owned Guaranteed Rate Field expires after the 2028 season, and the team has made it clear they have no intention of renewing. Last month, the team revealed a proposal to the city and state for a multi-billion dollar stadium complex at the heart of The 78, the controversial near-South Side site long seen as perhaps the city’s most economically potent piece of undeveloped land.

The scope of the proposal, created in conjunction with real estate developer Related Midwest, is impressive. White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf pitched a redevelopment plan for The 78 that includes a new stadium as the development’s “anchor,” with apartments, hotels and other projects. The project’s price tag is also noteworthy. In an interview with Crain’s Chicago Business shortly after its release, Jerry Reinsdorf revealed that the plan includes more than a billion dollars in various forms of public funding.

Included in these demands was the all-too-familiar threat of relocation, should the money not be found. According to Crain’s, “The team almost certainly will be sold after [Reinsdorf’s] death, and ‘the big money’ is in the hands of outsiders who want to move the team to Nashville or another location.” A spokesperson for the White Sox declined to comment for this story.

Continuing to occupy the current stadium is a non-starter for Reinsdorf, who told Crain’s “a new space in a livelier downtown area with shops, bars and other entertainment venues within walking distance” would be required to generate the revenue necessary for a good team. It’s not a new complaint. Noted architecture critic Blair Kamin observed in 1991 that “the park swims alone in a sea of parking lots, like the shopping malls of suburbia,” echoing the generally negative sentiment surrounding the feel of the new park. Homes and businesses between 35th and 39th street were demolished to make way for New Comiskey and the sea of parking lots, lending a bitter irony to Reinsdorf’s complaint.

Given the owner’s critical role in those failed design choices, many Sox fans have taken his latest comments with a healthy dose of cynicism. This is not the first time the team has flirted with taking its clubhouse elsewhere, or even the second. In the 1970s, they were nearly sold to a group planning on relocating the team to Seattle, a scenario that also would have had the Oakland Athletics taking their place in Chicago. Under Reinsdorf’s ownership a decade later, the Sox’s move to St. Petersburg, Florida was all but done before the Illinois legislature stopped the clocks to wave a funding deal for the current ballpark home in 1988.

That deal was panned by many from the get-go, with the state paying for more or less the entire stadium. That flow of money didn’t stop after construction was completed, either. Lost in the shuffle of Reinsdorf’s request for ten figures in new money is the fact that Chicago and Illinois taxpayers are still on the hook for money owed on the current ballpark, to the tune of tens of millions of dollars—with hundreds of millions of additional dollars having already been spent.

Funding terms weren’t the only thing about the new Comiskey Park observers took issue with. It was considered a flat-out ugly stadium, with Kamin describing the structure itself as “big and brawny, like many of the highly paid players who play in it. Will this building ever be beloved?” he asked. “Don’t bet on it.”

In subsequent years, the opening of well-received new stadiums in Baltimore, Cleveland, and Denver made New Comiskey look like a whiff in comparison, and it lasted fewer than fifteen years before an extensive, multi-year facelift turned it into the generally pleasant venue it is today. It might be on its third name and approaching forty years in its foundations, but functionally, the venue we see today is two decades old.

That facelift, which included a total reconstruction of much of the upper deck and outfield concourse, were entirely paid for by the Illinois Sports Facilities Authority (ISFA), the State agency responsible for administration and financial management of Guaranteed Rate Field. The ISFA is nearly entirely publicly funded, filling its coffers with proceeds from the hotel occupancy tax instituted to pay for the park’s construction, as well as millions in subsidies from the City and State. Virtually all money spent by the ISFA is taxpayer money.

Undertaken in several phases beginning in 2003, the cost of the renovations was reported to the public as $41 million, but further additions and hidden costs have driven the final bill considerably higher. High interest payments and a heavily backloaded payment schedule on the bonds taken out by the ISFA to finance the projects have left the total amount spent on the overhaul at more than $80 million, more than double the cost presented at the outset.

Thanks to the ISFA’s repeated refinancing of those bond payments, necessitated by their management of the disastrous 2001 Soldier Field renovations, it still hasn’t been fully paid off. Between the structural renovations and the Bar & Restaurant and multi-story gift shop built for the team shortly thereafter, nearly $50 million in debt relating to Guaranteed Rate Field is still scheduled to be paid off between now and 2032.

The ISFA has asserted that all debt for Sox Park will be repaid by the conclusion of the team’s lease, though it’s not clear how that will be the case, as the stadium’s debt has been merged with Soldier Field bond debt not scheduled to be fulfilled for several years after the White Sox’ intended departure. The ISFA did not comment for this story.

What may also be of concern to South Siders amid these new stadium requests is that tens of millions in tax revenue have been pouring into the current ballpark each year as far back as information is available. Since 2010, the ISFA’s Capital Improvements Fund for the park has reported more than $115 million in projects and maintenance spending on behalf of the White Sox. This included millions in baseball-related items for the team, with the agency picking up the tab for clubhouse renovations, batting cages and batting practice equipment, dugout furniture, training and physical therapy equipment, field netting, and video surveillance equipment.

Virtually none of the millions coming out of Chicagoans’ pockets makes its way back to the public side. The team’s annual rent to the ISFA averaged $1.9 million annually since 2010, and just barely eclipsed $2 million in 2022 and 2023. Despite receiving considerably more than they contribute, the Sox organization keeps almost all of the revenue generated by the ballpark, including money received from parking, merchandise, concessions, and all other sales within the park. Ticket sales are only taxed if the team’s annual attendance eclipses two million, a rarity in recent years.

Team revenue sheets are tightly guarded secrets, but total proceeds for the White Sox likely push well into the hundreds of millions of dollars annually. The Atlanta Braves, who are owned by a publicly traded company and required to release financial reports, reported $272 million in revenue in the third quarter of 2023 alone. Atlanta has been one of MLB’s best teams in recent years with a larger market share, and one would expect their margins to be higher that the South Siders’.

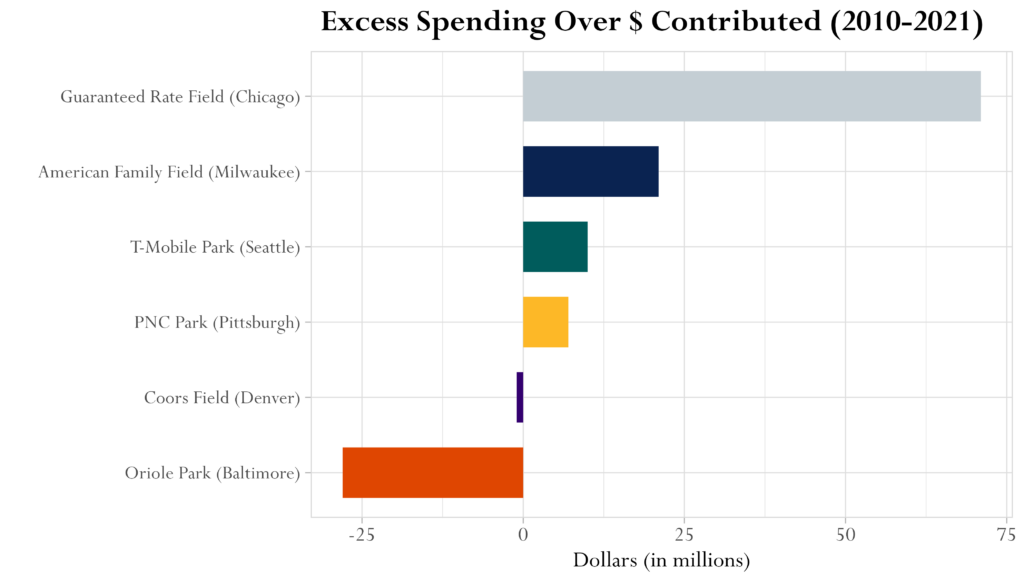

The Sox likely make enough money to raise an eyebrow at the degree to which their stadium is subsidized. With all expenses and debts included, Guaranteed Rate Field’s drain on government checkbooks is staggering: a combined $200 million since 2010, spent as Chicago’s public services fell into disrepair and Reinsdorf’s net worth has more than doubled to a cool $2.1 billion. In that time, ISFA has reported just $26.7 million in payments from the White Sox, barely 10 percent of what’s been spent on their behalf.

With a board of directors appointed in equal proportion by the governor and by Reinsdorf himself, the ISFA has been criticized as being under the thumb of the longtime figurehead, who also owns the NBA’s Chicago Bulls. In a 2013 wrongful-termination lawsuit against the agency, former chief executive Perry Irmer described it to the Reader’s Ben Joravsky as a “cash cow puppet” for the billionaire, alleging that she was sacked for attempting to increase payments made by the team.

Sean Dinces, the author of Bulls Markets: Chicago’s Basketball Business and the New Inequality, is intimately familiar with Reinsdorf’s way of doing business. Dinces was equally pointed in his characterization of the ISFA. “It’s a perfect example of a pseudo-governmental agency overseeing the massive transfer of public resources to a private entity,” he said. Reinsdorf “really started to break the mold in that he figured out ways to say, ‘Okay, I’m still gonna have the public be involved, but I’m also gonna find ways to not have to share anything.’”

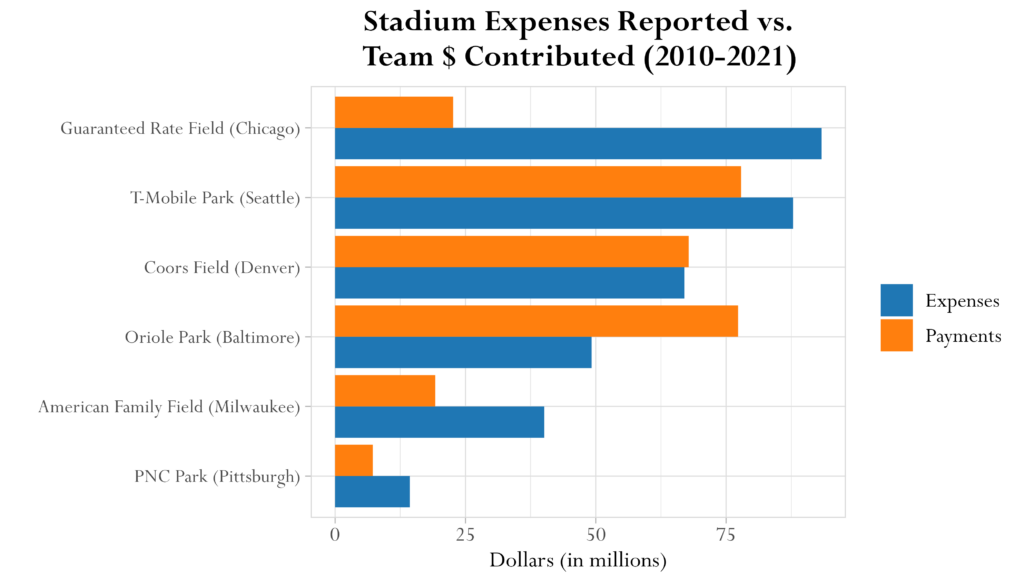

Even by the standards of professional sports owners—and taking debt service out of the equation—the disparity between what the White Sox give and what they take is enormous, in terms of paying for maintenance and upgrades. Many teams play in publicly owned and leased stadiums across the country, with most of them utilizing a government agency like the ISFA as a facilitator. But few have spent as much money on upkeep as the ISFA.

Comparisons with five other local agencies for publicly funded ballparks from whom the Weekly was able to obtain financial data show that Chicago’s public spending utterly dwarfs that of most other localities, with the White Sox paying for less than a quarter of their numerous requested improvements between 2010 and 2021, which were the years for with the Weekly was able to obtain data from all sources. All these ballparks opened within ten years of Guaranteed Rate Field.

The public is in the dark about most of these expenses, but even so, fan reception to the team’s ask has still been almost universally negative. The team’s near-move to Florida wasn’t that long ago, and many of those who remember it aren’t buying what Reinsdorf is selling this time around.

One longtime fan, a forty-year season ticket holder who requested anonymity due to their involvement with one of the team’s major sponsors, isn’t putting much stock in the chatter over The 78. Like many others, they believe the owner’s repeated threats have done a disservice to the community.

“Team owners may get to own a team, but I think they ought to be responsive to the city they’re in, and recognize that even though the people of the city don’t own the team, they do with their hearts. That’s what a loyal fan base is built on. That being the case, I really didn’t like [Reinsdorf’s threats] then, and I don’t believe them now.”

Sam Bartlett isn’t old enough to remember the near-move to St. Petersburg, but that doesn’t make him any less skeptical of the team’s claims. A lifelong South Sider and Hyde Park resident, Bartlett has the Sox logo tattooed on his arm, and feels this is just the latest development in a pattern of disrespect from the team towards its fans. “It makes me feel more lied to than I already am,” he said, citing the “meddling and brazen cost-cutting” that Reinsdorf has already imposed upon fans. “What team deserves a new ballpark but can’t give us a $1 hot dog night?”

The White Sox have pointed to the purported economic benefits of their vision for The 78, should it come to fruition. The proposal places the new stadium at the heart of a neighborhood development touted as a “$9 billion total investment,” and will create 22,000 permanent jobs on top of 10,000 construction jobs.

Geoffrey Propheter, a professor of public policy at the University of Colorado-Denver specializing in sports facility economics, spoke with the Weekly about the White Sox and publicly funded stadium subsidies prior to the release of Related Midwest’s proposal, presciently commenting on the promises often made during subsidy campaigns.

“It’s like clockwork. Every time there’s a subsidy debate, people are going to talk about jobs,” Propheter said. “They [often] express these jobs, particularly permanent jobs, in terms of job years…. Numbers will be thrown around like ‘30,000 jobs,’ but that number isn’t really 30,000 jobs. It might mean 1,000 jobs lasting thirty years [each], or thirty jobs lasting a thousand years.”

When asked for clarification, the White Sox and Related Midwest reiterated that the proposal represents 22,000 permanent jobs. They did not provide any information as to how they arrived at that number.

Beyond the specifics, Propheter thinks the benefits touted by proposals like Reinsdorf’s, which also promises an economic impact of over $4 billion annually, don’t pan out. “You can basically say the tangible benefits are zero,” he said. “And we’ve got decades and decades of economic research saying that it’s zero or super super close to zero.”

In spite of its broadly negative reception, the new stadium concepts were still exciting for many fans starving for something to look forward to. But despite Reinsdorf’s hope that preliminary construction will begin later this year, there’s little evidence that anything concrete is on the horizon.

A key difference between now and 1987, when then-Governor Jim Thompson facilitated the creation of the ISFA alongside Reinsdorf, is that current Governor J.B. Pritzker has not been subtle in his opposition to public stadium subsidies, calling himself “really reluctant” to even discuss signing off on the team’s request. Given how much the White Sox and Related Midwest’s plan relies on ISFA funding, a new deal without state involvement is highly unlikely.

“Some politicians realize that most of this is bluff work,” Dinces said. “More often than not, teams don’t have any actual concrete plans to move when they start this stuff. It’s more like, ‘we’re gonna probably do this anyway, let’s see if we can get them to pay for it.’”

This time, if Reinsdorf moves to make good on his relocation threats, there will be no midnight legislative sessions to stop him. And it’s not just politicians who are more inclined to call the bluff. With the team itself being nigh-unwatchable for more than a decade, the number of fans inclined to give ownership what they want is scant.

The forty-year season ticket holder canceled their plan over the winter, and for the first time since the stadium opened, will be buying tickets on a game-by-game basis this season.

As a less-invested South Sider, Beverly, the bartender, is more blunt. If the Sox leave, “I wouldn’t like it. It would suck,” he deadpanned. “But I would not be personally affected at all.” After a pause, the bar erupted with laughter as he added, “And I would act like somebody was taking my lick! It’s still our team.”

Malachi Hayes is a Bridgeport-based freelance writer and managing editor at South Side Sox.