“In this neighborhood, there are gangs, there are kids who don’t get attention who can get to the point of bringing drugs to sell inside school, or bully,” Esmeralda Gutierrez, a parent representative on the Local School Council (LSC) of George Washington High School, said in Spanish. “Now that there’s no officials taking care [of students], I’m scared that things are going to return to how they were before. I’m scared that shootings will start up again.”

To date, seventeen Chicago Public Schools (CPS) schools’ LSCs have voted to remove their school resource officers, or SROs, while fifty-five have voted to maintain them. The decision of whether to keep or remove SROs was left to individual schools, decided by each school’s elected Local Schools Council (LSC), which is made up of parents, teachers, community representatives, and a student representative.

The initial vote by the Board of Education—a seven-member board appointed by Mayor Lori Lightfoot—on June 24 resulted in a narrow 4-3 vote to keep the $33 million contract between CPS and CPD. This initial motion to terminate the CPD contract was presented by board member Elizabeth Todd-Breland. They voted again on August 26, 4-2 with one abstention, to renew its contract with the Chicago Police Department. For one year, the board has cut the contract from $33 million to $12.1 million.

For those that have chosen to keep their SROs, justifications often sound like Gutierrez’s—anecdotal fears of gangs, fights, or school shootings. But for many students attending CPS high schools, the reality of SROs’ roles within their schools is very different.

“[George] Washington High School is ninety percent Latinx and five percent Black or African-American, and our SRO, his name is Alex, is actually very friendly with all of our students because most of our students look and speak the same as him. But it was always very obvious that that connection wasn’t there with Black students in particular,” Trinity Colon, a junior at Washington and the student representative on the school’s LSC, said in an interview. “I’ve never really seen them positively interact with Black students in the way that they positively interact with Latinx [students] and that’s just leaving that implicit bias there,” she said.

In addition to these concerns, Colon noted the amount of misconduct complaints against both of the SROs in her school. One SRO, Alexander Calatayud, has had fifty-seven misconduct complaints against him, a number that has not been updated in his files since 2016 and that is greater than the number of ninety-five percent of CPD officers. He also has twelve use of force reports, which are self-reported and may not be comprehensive. Six of these were for using a taser on Black teenagers, four of which took place in a public school. Washington’s other SRO, Salvador Passamentt, has twenty-two complaints against him and four use of force reports, each of which is also for using a taser in public on a Black male or female.

“We’ve been posting a lot on Facebook about the movement and trying to get the word out and trying to mobilize our students and our parents,” Colon said, and noted that using social media to voice her opinions has resulted in some backlash. “There has definitely been some harassment from our SRO towards me and other students on social media.”

In screenshots Colon provided to the Weekly, Officer Catalayud is seen to be making antagonistic comments in response to posts by students and alumni. In one comment, he responded directly to Colon, calling her out by name. In another comment, he wrote, “For those that aren’t as ‘PRIVILEGED’ as some & may not understand stuff written in ENGLISH…” presumably referring to Latinx students, “All I have to say is that if you remove CPD from our schools and someone’s child gets beaten or is a victim of bullying, do you really think teachers will protect your child? GOOD LUCK WITH THAT!!!!”

Though Colon and other students and teachers reached out by email to the administration about their SRO engaging in bullying over social media, they received no response. Their demands included additional support for the students who were involved in the campaign to remove SROs from Washington, and that the SROs be held accountable to the same policies to which CPS staff are held, including Anti-Bullying and Staff Acceptable Use Policy IX. Social Media/Online Communication.

[Get the Weekly in your mailbox. Subscribe to the print edition today.]

“If we would’ve kept those SRO officers, honestly, it would’ve been a really uncomfortable situation seeing them in the building if we were in person,” Colon said. But, she said, many other members on the LSC did not seem to understand— or even attempt to understand— the perspective of the students advocating to remove SROs. The strongest arguments for keeping SROs in the school in response to the data and testimonials were “a lot of ‘what ifs,’” she said.

The final vote was 6-5 in favor of removing SROs—a narrow vote which would have likely been 6-6 had LSC member Peter Chico, a police officer, not excused himself from the vote. “I was in closed session with LSC members and I they genuinely felt bad [for Catalayud],” and they felt he didn’t deserve to have his public records put out there,” Colon said. “This just kind of shows how they protect cops more than they protect students…They’re just trying to protect the system.”

“I definitely felt like [our LSC members] weren’t listening to youth voices,” said Colon. “I felt like whatever we said to them was coming out of the other ear.”

What, then, tipped the narrow vote in favor of removing SROs at George Washington High School? For LSC members who chose to listen, it was the extensive student activism. The pre-existing infrastructure formed by clubs like the Student Voice Committee, the Patriot Peace Warriors, and the Black Student Alliance primed the student-led operation by giving students a space to host anti-racist discussions. A network of students across these organizations created a unity conference to further their goals. “We were already having that conversation…that definitely just ignited when I got that first email about the LSC agenda speaking on CPD in schools,” Colon said.

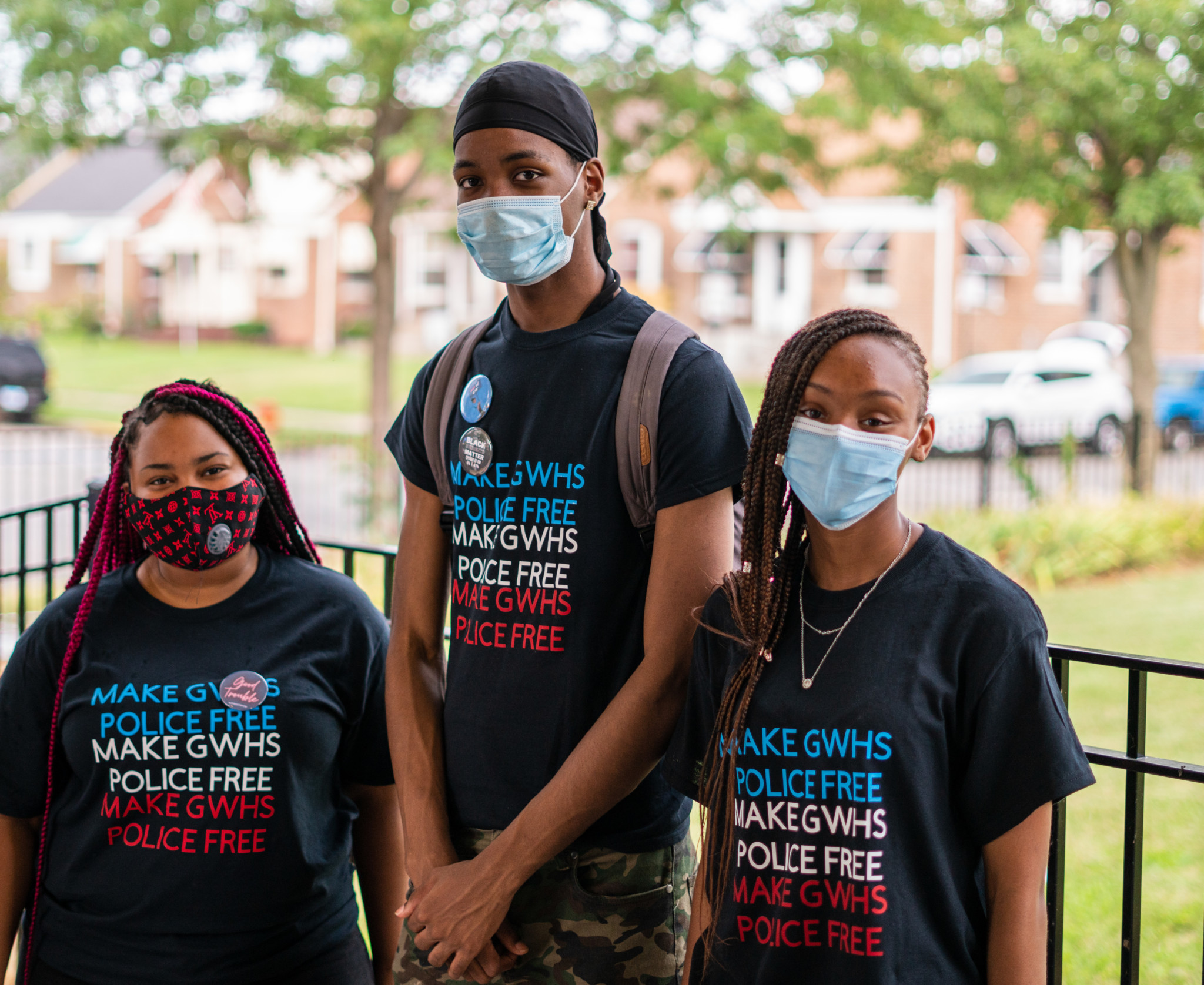

She created a petition called “Make GWHS a Police Free School” which garnered 797 signatures. Students held two consecutive weekend protests and created an Instagram account that posted testimonials of Washington students regarding their experiences with SROs. “With elaborate email planning, email campaigns, and showing up at every single LSC meeting speaking in that public comment…I think that we did honestly convince a few LSC members to get our on side and eventually ended up winning the vote,” Colon said.

Student Activism Across CPS

Washington is not alone when it comes to strong student activism. Student-led groups across many CPS schools have been pushing to remove SROs as LSCs continue to vote on the issue. The #PoliceFreeSchools Coalition includes organizations such as Students Strike Back, a group of students who attend neighborhood high schools on the Southwest side of Chicago, and the Brighton Park Neighborhood Council, a community-based nonprofit organization serving Chicago’s Southwest side.

Together, these organizations have been working to collect data about CPD in CPS and have been using this data to power the organized group of students advocating to remove SROs in CPS. Their #CopsOutCPS Report found that the 180 SROs and twenty-one School Liaison Supervisors assigned to CPS (before the LSCs began voting) had a total of at least 2,354 misconduct complaint records against them.

The report also noted that police in schools disproportionately target Black students. More than ninety-five percent of police incidents in CPS involve students of color, and Black students are subjected to police notifications at four times the rate of white students in Chicago. According to data from Chicago Public Schools, police notifications have led to arrests of Black students at a rate of nine and a half times higher than white students—out of the 11,527 student arrests in Chicago over the past nine school years, 9,001 have been Black students. This is more than seventy-six percent, even though Black students accounted for 36.6 percent of CPS enrollment during that time.

CPS students have also been working to collect first-hand testimonials regarding other students’ experiences with SROs. CPS Alumni for Abolition, a group of Chicago Public Schools alumni working towards police-free schools, collected over 250 testimonials from fellow alumni and students. “The ones that I can lump into a big category were the twenty-plus testimonials that we had where students talked about sexual harassment, either directly at the hand of police officers, or at the hands of the other students and the officers were there and just watched and did nothing,” Kysani London, an alum of Northside College Prep, which was the first school to vote out SROs. “Who do you report the officers to if they do this to you, if you’re sexually harassed by them?…There’s no one.”

“Police at Jones harassed girls as soon as they turned eighteen and made jokes about them being ‘legal.’ They also only enforced the dress code when girls didn’t play along with their advances,” Cristal Alvarez, who graduated from CPS in 2018, wrote in her testimonial. “They constantly sexually harassed young women at Whitney Young under the guise of being those, ‘hey, girl…where’s my hug?’ type of pervs,” an anonymous testimonial from someone who graduated from CPS in 2005 wrote. “By far the most traumatic of those experiences happened when a boy sexually harassed me, picked me up and slammed me against a locker, and then felt me up against my will while the officers did NOTHING but stand there and laugh,” wrote Nora Lubin who graduated from CPS in 2013.

Student testimonials also testified to the disproportionate punishment of Black students. Mitsuru Nelson, who graduated from CPS in 2009, said, “Liaison officers would corner Black and Latinx students specifically on baseball fields in Oz Park, in hallways, and throw them against buildings or onto the floor for no reason and harass them till they ‘found something.’” . An anonymous source who graduated in 2016 said, “Police officers would more often than not target Black students and other students of color as opposed to other wealthy white students, whether through seemingly random searches or simply by observing their every move.”

In their CPS Alumni Open Letter, which has garnered around 3,000 signatures, they demand the termination of CPS’s district-wide contract with CPD. However, these efforts were not enough to sway the Board of Education’s vote on June 24 to renew the contract. Vivekae Kim, a Northside College Prep alum and one of the main organizers for CPS Alumni for Abolition, said that the board was still getting caught up in dominant narratives about police in schools instead of listening to the consistent demands of students. “The city right now is just rallying around unproven and anecdotal senses of what constitutes public safety without regard for student voices,” Kim said. “The fact that we’re still justifying the presence of police in schools when it’s clear from the data that the system is inherently racist, yet the response that’s given to students is, ‘Just keep waiting. Just keep waiting for those numbers to get lower and lower. We know that there’s a disparity, but we are not willing to engage with your reimagining of safety and resources that should be in school,’” she said.

Kim provided public comment on the presence of SROs at the first meeting at Northside College Prep on June 16th with other community members. “They really brought it to the table. After that, our two teacher representatives were really on the side of that alumni group and they were doing a lot of pushing while that group was doing their speaking in our meeting,” Luna Johnston, a senior at Northside College Prep and the student representative on its LSC, said.

In the lead-up to the next meeting in which LSC members would vote on whether or not to keep SROs, Johnston organized students in writing a letter and conducting a survey (of the 194 responses to the survey conducted, 183 said they were against SRO presence) that she could share at the next LSC meeting. Students and alumni organized a protest on July 5. “I requested that we have a public comment not only at the end, but in the middle [of the meeting] before we made the vote because I wanted to make sure that everyone… understood how the students felt before we made any binding decision,” said Johnston. Almost all of Northside College Prep’s members of CPS Alumni for Abolition were present at the next meeting—most of whom provided public comment, and the vote to remove SROs from Northside College on July 7 was unanimous, with eight LSC members voting in support of the students and one member abstaining from the vote.

Nancy Bigelow, a teacher representative on the LSC of Benito Juarez Community Academy, relayed the pivotal role that student activism played in her school’s recent decision to remove SROs. Last fall, the school’s LSC voted to keep SROs. “I don’t know that it felt like at the time that it was that huge of a vote, because it seemed at the time like a no brainer. You either get two extra bodies in your school… or you get nothing,” Bigelow said. “It’s not like we were given much to vote on.” But this year, her mind was changed. “Overwhelmingly we had a lot of students and community members who spoke… I received I don’t know how many emails from mostly students [and] some faculty, and all requesting that we vote against continuing the SRO budget.”

A False Choice: What LSCs Lack

Although individual schools’ LSCs are voting to remove their SROs, the question remains as to whether this is a sufficient response to the needs of students across the district.

“The Board of Education has pushed this vote onto our LSCs knowing that most of these school councils have the implicit bias,” Colon explained. “And not only that but we know that the majority of CPS staff is white, so it does end up in that position where you have schools that are predominantly Black but their LSC isn’t properly representing them.” Colon said that she has felt this dynamic play out at Washington as well. “In my case… we have instances where our LSC is predominantly Latino and so is our school demographic, and the anti-Blackness is integrated in that sense.”

Andrea Ortiz, the lead organizer of the Brighton Park Neighborhood Council (BPNC), also expressed concerns about inadequate representation of students in LSC decisions. “A lot of the representatives on these LSCs are not involved in the community,” Ortiz said. “We don’t even know who they are.” Ortiz said that LSC meetings tend to be structured around the principals’ agendas, most of whom do not understand or agree with the call to remove police from schools. “[They] are organizing the meetings around the vote for the police out of schools without any notification so that folks aren’t able to go and testify. And they happen so fast,” she said.

Many of the organizations in the #PoliceFreeSchools coalition have been pushing for the termination of the contract between CPD and CPS, not only as a way to remove a harmful presence from the school, but also as a way to redirect funds towards more formative resources. Ortiz said that BPNC has been pushing for trauma-informed personnel, restorative justice supports, counselors, and nurses that “are really going to help support students and their needs, and address harm and prevent harm from happening, and not just react to harm.”

Many student activists are concerned that if LSCs vote to remove their SROs, the school won’t receive the money that would have gone toward their salaries. “It’s just a false choice,” Kim said. “The whole point is not just to remove police as a negative presence in the hallways of schools, but [also] to take those resources and to give them to the things that students actually need.”

Jesse Sharkey, the president of the Chicago Teachers’ Union (CTU) , explained further why the current process of delegating this decision to LSCs would not result in more money for other resources. “The contract is approved centrally. If they believed that the LSCs should decide, they would cancel the contract, give that money to every single LSC, and let the LSC decide how to spend it, and they could hire police if that’s what they wanted to spend it on,” he said. “But that’s not what they’re doing. They’re approving a central contract, going to LSCs and saying, ‘We’ve approved this already, do you want your share of what was already approved?’”

While these discussions continue to take place, students and activist groups across Chicago remain worried about the irreversible harms caused by the presence of police officers in schools. One major concern is the practice of entering students into Chicago’s gang database, which has a reputation of being both inaccurate and permanent. There is currently no due process or protocol for entering someone’s name into the database and no way to be removed from the database even if the information is incorrect. The Cook County Board voted to dismantle the gang database in February of 2019, but the vote has yet to be implemented.

“We made the connection that [students] are being added into the gang database because of the police officers in the building, and being targeted and being labeled as gang members because they’re wearing certain colors or they’re hanging out with certain people or they live in a certain community,” Ortiz said.“And [they are] inadvertently targeting our Latino students who may be undocumented that then get placed in the gang database and are put at risk of deportation.”

Accusations on the gang database stay on students’ records and can lead to deportation, lost jobs and housing (or an inability to find jobs or housing in the future), and higher bails. But often, youth in Chicago Public Schools do not even know their names or the names of their friends have been put down. “I think the number is around 60,000, of youth that we think are on the gang database. But because they’re minors we’re not able to access that,” Ortiz said.

“[The students are] targeted in their own community and scared to walk around their community because their SRO may see them out with their friends or associate them with someone,” Ortiz said. “Or their SRO may see them out on the street with someone, and then go to school the next day and go up to them and say, ‘Hey I saw you hanging out with this person who’s a gang member, are you a gang member?’ and then place them on the gang database.” And while students can file a request through the Illinois Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) to see their information, Ortiz gave an example of the organization Blocks Together helping youth file such a request, which resulted in police officers showing up at their house with the letter to intimidate them. “So we’ve been scared to FOIA that information for students because we didn’t want to put them at risk or have them be targeted,” she said.

According to the new contract between CPD and CPS, SROs will no longer be allowed to enter student information into the gang database. Other guidelines put forth by the new contract include enhanced training and more requirements for cops to work in schools, and the board has given CPS seven months to create a plan to develop alternative school safety best practices.

But many students, alumni, and organizers believe the situation is too urgent to wait for individual LSCs to remove the SROs from their schools. “The fact that students are just being asked to wait is just unconscionable because CPS students have been waiting for a long time,” Kim said. “When we’re talking about getting police out of schools, we’re talking about a program that’s anti-Black, that violates the civil rights of the students, and that’s up to the Board [of Education],” Ortiz said.

Sharkey, who taught at both Chicago Vocational and Senn High School before becoming the president of the CTU, emphasized the detrimental effects police presence in schools can have on students’ education and livelihood. “People need to get their head around [the fact] that there are big sectors of the population that don’t see police as ‘Officer Friendly’ who helps them get their cat out of a tree, but see police as a threat,” he said. “So especially for undocumented students, the idea that the police officer in their school is someone that’s going to make them feel safer flies in the face of a lot of people’s lived experiences.”

And many students and activists have continually said that reform doesn’t work. “Reform isn’t an option because…that usually leads to an increase in the police budget,” said Ortiz. “When we showed that police officers were not getting any trainings in the schools, the mayor then used it as an excuse to increase the SRO budget from twenty-two to thirty-three million. Training doesn’t work.”

“There’s been a lot of data that shows that restorative justice and transformative justice practices and trauma informed personnel has really helped a lot of youth by addressing harm,” Ortiz said.

According to all of the activist groups that the Weekly spoke to, what students really need are resources and programs that will address student behavior in supportive, preventative, and restorative ways. “You get to situations where students are in a crisis at home, and rather than giving them any kind of actual attempt to understand the crisis and respond to the things they need, you’re simply punishing them or ultimately trying to expel them,” Sharkey said. “The adult people who run the most important institution in your life, your school, are prosecuting you, building a case against you, trying to get you kicked out.”

For those who have similar concerns as Gutierrez, the response is that in the long run, mental health and other community resources will do far more preventative good than the police which can only respond to isolated incidents. Mary Winfield, a teacher at Benito Juarez High School, said that in the short term, police are not even necessary to respond to incidents that teachers may be unable to handle themselves. “I have never, in twenty-two years, ever encountered an incident at my school that I felt required police,” Winfield said. “There’s been fights, there’s been gang activity. Our first order of activity is de-escalation within the classroom… If it’s a physical altercation, the security staff at our school if they are able to, will come and help.”

The school has four security guards who are unarmed and hired by the school, whose main focus is de-escalation. Winfield said that teachers can also call in school social workers or counselors to assist. “In general, they see the students every day, all the time in the hallways. So they have a lot more of a connection,” she said. Winfield noted that the school’s SROs, in contrast, tend to stay in their offices for most of the day. “I very rarely have ever seen two kids who really want to fight each other. They’re just having a really bad day and it sucks sometimes to be a teenager.”

Dealing with students’ social-emotional behaviors, according to Winfield, is a job much more fitting for counselors and other school staff.

“The teachers shouldn’t need the armed, uniformed authority of the state in order to get respect in the school,” Sharkey said. “What we could really use would be people who are trained, who have clinical experience, youth intervention specialists, social workers, counselors, that kind of stuff is what we really need to address student behavior. Because it is, after all, the behavior of children, right?”

Update 9/16/20: A quote in this article has been edited to reflect that the speaker is speculating on what LSC members felt, rather than reporting their expressed sentiments.

Madeleine Parrish grew up in New Jersey and is currently an undergraduate student at the University of Chicago studying political science. She last wrote about how churches on the South Side uplifted their communities during COVID-19 despite financial hardship.