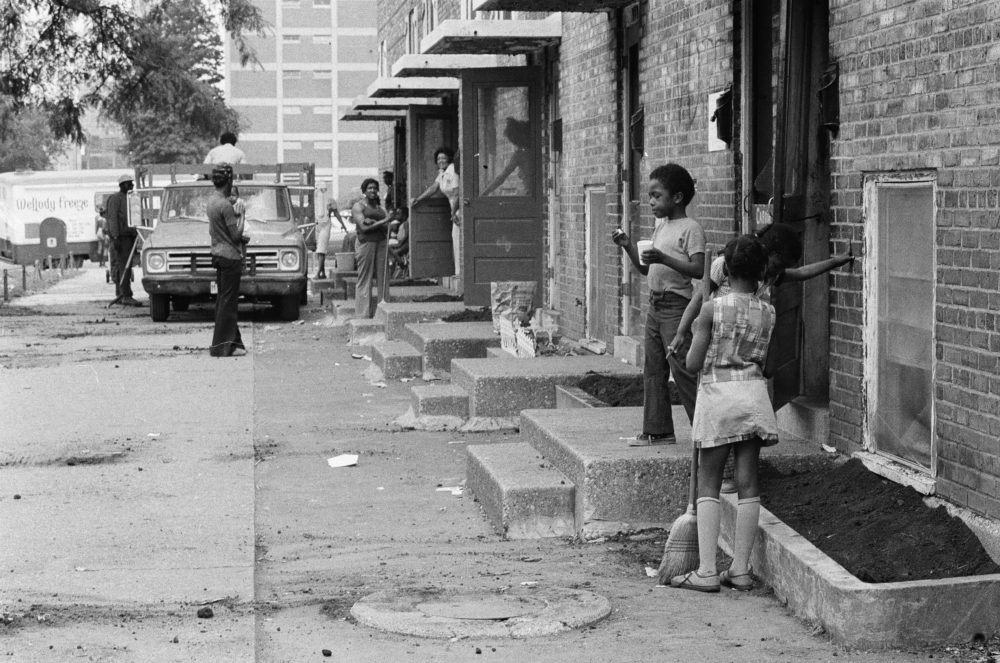

Originally intended to replace overcrowded, deeply impoverished neighborhoods, Chicago’s midcentury public housing developments initially offered significantly better living conditions to residents, and for a time were, as author Dawn Turner told the South Side Weekly, “bastions” of stability that “conferred dignity on the residents.”

But subsequent decades of disinvestment and neglect by federal and municipal authorities, combined with entrenched racism from the political machine and a police department with a long history of brutality, led many public housing developments in Chicago to become places where generations of Black families were trapped in poverty amid violence and extreme segregation.

Federal and municipal agencies both had a hand in the decline of public housing in Chicago, as well as in the more recent attempts to reverse it. And at both the federal and local level, agency oversight of public housing—or the lack thereof—has consistently reinforced the city’s segregation.

Terms to know:

Area Median Income: The middle point of an area’s household income distribution. AMI’s are determined differently by the income distribution of a given city and region.

Low-Income Housing: According to HUD, in order to be considered low-income and therefore qualify for public housing, households must make a gross income of eighty percent or less of the AMI for their local Housing Authority

Mixed-Income Housing: Housing developments which include varying levels of affordability in the same property, including market-rate and affordable housing.

Scattered Site Properties: Individual or small groups of public housing properties, rather than full developments. There are scattered site properties in all seventy-seven community areas of Chicago.

The New Deal: A series of economic development programs started by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Great Depression. The New Deal was meant to stabilize the economy and offer relief to those most impacted by the Great Depression.

Public Works Administration: An agency set up by President Roosevelt to oversee and carry out the New Deal. The PWA spent about $4 billion on education buildings, public health facilities, court houses, and sewage disposal, as well as roads, bridges, and subways.

Housing Choice Voucher (or Section 8): Federal funding from HUD that helps families pay for rental housing on the private market. Participating families contribute thirty to forty percent of their income towards housing and HUD pays the remainder directly to the property owner.

What is the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) and what is its role?

Created in 1937, the Chicago Housing Authority is a municipal not-for-profit agency whose primary objective is to provide housing options for low-income families. It was founded under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Public Works Administration, which came about as part of the New Deal.

As one of eighty public housing authorities to take part in the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Moving to Work Program, CHA currently provides homes for more than 63,000 households in Chicago through four different types of public housing: family, senior, scattered site, and mixed-income.

Currently, there are just under 7,000 family-specific units on fourteen different public housing properties. As for seniors, there are 9,000 units of housing on forty-three different properties throughout the city. CHA has 2,800 units of scattered site housing, which can be found in all seventy-seven community areas. Currently, forty-four properties qualify as mixed-income.

An abridged history on the Chicago Housing Authority

The CHA was created in 1937. Of the first three CHA developments whose construction began in the 1930s—Jane Addams, Julia C. Lathrop, and Trumbull Park Homes—Lathrop, on the Near North Side, and Trumbull, on the far South Side, still stand, having undergone recent renovations. By the late 1950s CHA owned over 40,000 units of housing, making it the city’s largest landlord.

But even the early days of public housing were rocky. In 1937, the agency adopted the “neighborhood composition rule,” which required residents of public housing developments to be of the same race as residents in the neighborhood surrounding the development. The policy, which ostensibly was put in place so “that public housing should not disturb the pre-existing racial composition of neighborhoods where it was placed,” further encouraged and enforced segregation.

It also concentrated residents into densely populated areas. An example of this were the Robert Taylor Homes, completed in 1962, which spanned two miles along State Street, from 39th to 54th, in close proximity to other developments including Harold L. Ickes and Stateway Gardens. The three housing developments combined had nearly 7,000 units of housing.

In 1966, a group of tenants led by Altgeld Gardens resident Dorothy Gautreaux sued the CHA, claiming that “by concentrating more than 10,000 public housing units in isolated African American neighborhoods,” both CHA and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) were violating desegregation laws. In 1976, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of Gautreaux. From 1976 to 1998, the CHA’s Gautreaux Assisted Housing Program moved 7,100 Black households to integrated housing throughout the Chicagoland area.

In 1995, the federal office of Housing and Urban Development reclaimed control of CHA, arguing that the city had mismanaged and neglected public housing. Soon after, HUD advocated that the high-rise developments, which had become areas of high crime and concentrated generational poverty, should be demolished. In 1999, former Mayor Richard M. Daley did just that, taking the agency back under city control and launching the Plan for Transformation in 2000.

What is the Plan for Transformation?

The Plan for Transformation sought to demolish 25,000 units of existing public housing and renovate and replace the developments with upgraded facilities and housing. The plan also sought to further integrate public housing residents with non-public housing residents through mixed-income housing developments. The plan was set to be completed by the end of 2017. Today, according to CHA, eighty-eight percent of the plan is complete.

Its execution caused severe displacement for residents across the city. At the Cabrini-Green high rises on the city’s Near North Side, CHA demolished 1,324 units of public housing, promising to replace the towers with mixed-income developments. The neighborhood demographics have changed significantly since the towers’ demolition, becoming whiter and more affluent.

The goal of mixed-income housing is to place poor residents in housing developments with more affluent residents, following the belief that placing residents of various economic backgrounds in similar housing will help provide poor residents with a higher quality of life and increased agency. However successful this theory may be, the opportunity was offered to very few public housing residents.

To start, only 1,300 of the nearly 17,000 remodeled units under the Plan for Transformation were in mixed-income developments. Many residents were unable to meet the set of requirements in order to qualify for the sought-after mixed-income housing. These requirements included proof of income, good credit scores, and background checks—a challenge for many. At the start of the plan, for example, over half of Cabrini-Green residents were unemployed.

In response, some residents sought to stop the plan altogether and even pursued legal action, claiming that CHA’s displacement of residents was unlawful. In two cases against CHA, the courts sided with residents on the grounds that CHA’s “abrupt and unilateral” plan to relocate residents was in violation of the Fair Housing Act.

When public housing developments were torn down, where did the former residents go?

The Plan for Transformation promised not only new developments but new opportunities for public housing residents. A major component of the plan was integration and an increased quality of life carried out through mixed-income housing, but that promise was never fully fulfilled.

According to data published by WBEZ in 2017, less than eight percent of the nearly 17,000 households under the plan live in mixed-income communities.

About twenty-one percent are utilizing Housing Choice Vouchers (also known as Section 8) in the private market, 15.97 percent live in traditional (non mixed-income) public housing, 11.99 percent were evicted, and therefore are not eligible for a Section 8 voucher or relocation to other housing developments, 9.59 percent have died, and 33.82 percent are living without a government subsidy or assistance.

Geographically speaking, many residents stayed in Chicago and migrated to different neighborhoods. Those heading to mixed-income or scattered housing sites primarily moved to the North Side, while those using vouchers in the private market predominately relocated to the South and West Sides. Others left the city altogether, heading to the south suburbs, in a growing exodus of families hoping to to raise their children in a safer environment outside the city.

What are the City and CHA doing about affordable housing now?

In 2017, the year the Plan for Transformation was meant to be completed, WBEZ reporter Natalie Moore published an extensive analysis of the status of public housing developments. While thousands of units were demolished at South Side developments such as Stateway Gardens, Robert Taylor, Ida B. Wells, and Harold L. Ickes, little replacement housing has been built. At Robert Taylor, where 4,321 units of housing once stood, as of 2017, CHA had constructed just 335 units of a promised 2,388. At Ida B. Wells, CHA promised to rebuild 3,000 of the 3,500 units, but as the end of the plan drew near, only 348 new units had been built.

In 2018, Hyde Park native and journalist Ben Austen published High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing. Researched over seven years, the book chronicles the lived experiences of some of those who called Cabrini-Green home.

“The ongoing problem is that we didn’t solve anything,” Austen said. “The Plan for Transformation’s mission was to break up concentrated poverty, and that was going to justify all of the means that were really problematic and punishing and cruel. And the truth is, we didn’t break up concentrated poverty because this is the city we live in twenty years later.”

What’s next?

In December of 2021, Mayor Lori Lightfoot announced the largest investment in affordable housing in Chicago’s history. As a part of the investment, twenty-four developments located on the South and West Sides will create or preserve up to 2,400 affordable rental units. Of the planned units, 684 will be family-oriented while 394 will be devoted to residents making less than thirty percent of the area median income. Five of these projects are taking place at existing CHA developments while others are in neighborhoods surrounding them. The developments are split into four different tract areas, each focusing on a specific kind development: opportunity, redevelopment, transitioning, and preservation.

This investment doesn’t stray far from programs CHA has been relying on in recent years. Considering CHA’s significant decrease in staff for public housing, the agency has repeatedly relied on private-public partnerships to bring affordable housing to Chicagoans. The post-Plan for Transformation public housing landscape has shifted into one where the public is no longer in full ownership of its housing, creating more challenges for low-income residents to access the housing they need.

Grace Del Vecchio is a Philadelphia-born, Chicago-based freelance journalist primarily covering movements and policing. She also fact-checks for the Weekly.

I remember when I was little my mother and I stood in line to get 7 shots in one on my left shoulder and when they were getting ready to move me to a different neighborhood we was the only white family left and even though they put tar all over us and tried to put us out of whatever they were trying to do I was hearing bits and pieces that if you had to go back you would need a machine gun or you would be dead k

I recently received the housing choice voucher after being on the waitlist for 10+ years. It was unexpected to receive the letter as I forgot I signed up, also I didn’t think that I would qualify anymore, but apparently I do. Now, I am grateful for the opportunity, but it can definitely be more trouble then it’s worth. I’ve been waiting for almost 2 months for CHA to complete paperwork, inspections, and rent determination. All this happens after you’ve been approved by the property manager, and trust qualifications depending where you are is not simple! We’re talking 700+ credit, no background, no BR’s and plethora of other things. And it’s such a relief to be approved, and then BOOM! CHA takes forever with their paperwork, and now your unit and application is in Jeopardy of being cancelled, because at the end of the day this is still a business. And even when it’s all said and done, if you waited 2 months and CHA decides they’re NOT going to match the asking rent price ex: rent is $2,000 CHA offers $1900, So now there’s the defeat of having to start all over when CHA only pays 30% ANYWAY! Again I appreciate the help, but it feels as if CHA wants it participants in particular areas and it’s disappointing to say the least. And again why I say, it can be more trouble then it’s worth.