This year has seen three high-end grocery stores open their doors for residents on the South Side, with much fanfare and with varying discussions of food accessibility. These stores—Mariano’s in Bronzeville and two Whole Foods, one in Englewood, the other in Hyde Park—are undoubtedly welcome additions to neighborhoods that have in the past been categorized as food deserts, in the case of the first two, but the issue still remains that thousands of Chicago residents live without access to healthy foods, especially fresh produce. Currently, Chicago has what the Illinois Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights deems “low food access zones” in Washington Park, Greater Grand Crossing, Pullman, West Pullman, Roseland, South Deering, and South Chicago.

More than just an inconvenience, this skewed produce distribution has an impact on the health of residents in low-access neighborhoods. In 2011, a National Minority Quality Forum survey found that in a Chicago food desert, between forty-five and fifty-five percent of residents suffered from stage two chronic kidney disease due in part to lack of access to healthy foods, as well as lack of access to health care and low wages. A high-end grocery store may help, but will not resolve these issues of access and health.

Then again, supermarkets are not the only resources communities have. There are alternative sources of fresh produce—farmers markets, urban farms, and community gardens. Today, over one hundred community gardens thrive in Chicago, a long tradition that began in earnest in the 1940s with the Victory Garden movement, and has grown in recent years. And as Reverend John Ellis from the Greater Englewood Garden Association told me, “A community garden is designed for everyone.”

Despite this, the issue of produce distribution and access still seems to stick stubbornly on the South Side. The effects of initiatives to combat food deserts in these communities manifest in subtle ways that don’t show up in statistics, which gives the impression that little progress has been made. But even unnoticed, community members have been working hard to combat produce inaccessibility, recognizing that two categories of produce distribution are particularly well poised to address issues of accessibility. Community gardens have a strong foothold on the South Side, products of both passion and localized frustration. And food distribution companies, known for catering to the wealthy, are expanding their reach—using their resources to change the food landscape. Both produce sources face similar challenges of profitability and responsibility.

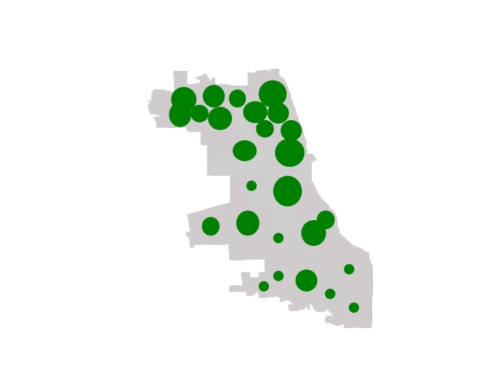

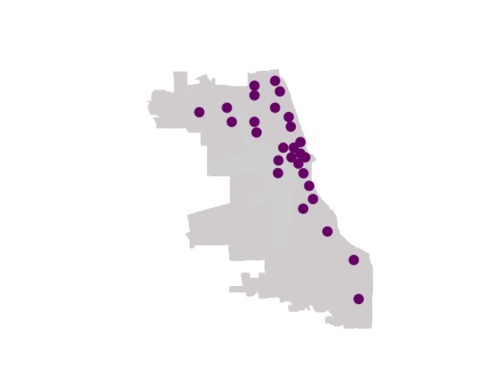

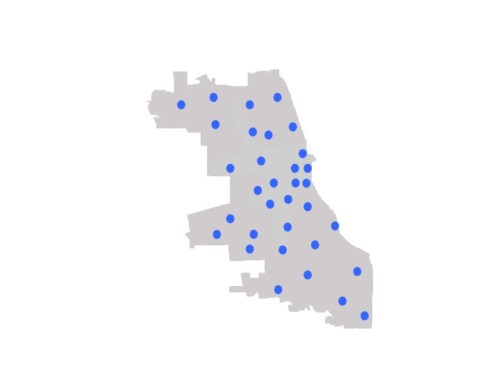

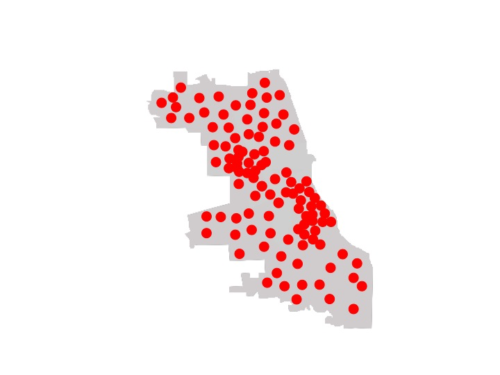

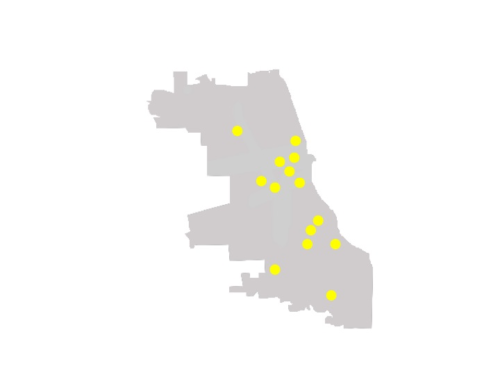

These maps show the distribution of five food services across Chicago. Green dots represent Peapod, purple dots Instacart stations, blue dots Door to Door Organics, red dots community gardens, and yellow dots urban farms. Larger dots indicate greater accessibility (e.g, how many days a week the service is open or delivers). (Data visualization by Zoe Makoul)

Some of these solutions are coming from expected places. Among established gardening organizations, such as the Greater Englewood Garden Association, and established farms like Growing Power, Growing Home, Windy City Farmers, The Plant, and the Gary Comer Youth Center rooftop farm, newer, smaller gardens have been sprouting up in greater numbers in recent years. One such newer initiative is Cooperation Operation, a small urban renewal project and community garden in Pullman founded by seventeen artists, community organizers, business people, and retired Occupy movement activists. In 2013, they moved into a house together and decided to build a garden for the neighborhood in an abandoned lot.

The lot had been a paint processing facility and had stayed unoccupied for several years. In the 1990s, the Environmental Protection Agency partially remediated the land, but the toxicity of the soil remained a concern until the Cooperation Operation planted mushrooms to increase nutrient levels, according to Liz Nerat, Cooperation Operation co-founder. Nerat, an artist and musician from West Rogers Park, describes the EPA remediation as “not really a solution, just a temporary thing to make it not terrible.”

Back in 2013, when the Cooperation Operation began, the lone Walmart that now sits in the neighborhood didn’t yet exist. Nerat continued her account as she picked earthworms out of the mulch and set them down in the soil. “There are very few places to get healthy food, to get healthy and cheap food. Accessibility was one of our main reasons for starting this. You shouldn’t have to live next to a Whole Foods to eat healthy.”

During my interview with Nerat, she gave me a brief tour of the garden, which, in April, was mostly growing onions and chamomile, before handing me a shovel and a wheelbarrow. As we got to work laying mulch out for a wheelchair accessible path through the herb gardens, Nerat shouted her philosophies over the wind. “We wanted to create a more tangible solution that would help people be more self-reliant,” she explained. “The idea is that you come and you contribute, and this is yours. You have this as much as we have this. We don’t charge for anything. People are able to come and we teach them how to take care of the garden, and then they are able to take what they want home with them.”

The Cooperation Operation is an oasis of sorts. Hidden on 114th Street and Langley Avenue, it looks a bit like an art project. Most of the fruits and vegetables are grown in repurposed boats and cinderblock troughs. There are so many hand-painted signs and magnificent trellises in the space that it’s hard to imagine that in 2013, all that existed under its name was a Kickstarter campaign and a petition to the alderman.

Nerat’s favorite thing about the Coop Op, she told me, is “getting a bunch of teenagers who don’t care where food comes from and think gardening is stupid, and they’re like, ‘This is boring, it’s hot, and I want to go to McDonald’s,’ since there’s a McDonald’s right across the street. But we get them into it and show them everything, and let them taste some food, and they see why this is important for the South Side of Chicago. Sometimes they come back and they bring their families. And that’s the goal. This is fun, it’s good for you, and it’s not difficult.”

I asked Nerat if she thought the people who used the garden the most were, in fact, people who don’t live near a Whole Foods. On the Saturday I spent there, a few volunteers were from Pullman, but many had traveled from the North Side. She paused, then told me that they have a little bit of a different group this year, because they’re expanding their classes and their workshop series. Many of her friends come down from the North Side for the open mic nights or the outdoor yoga classes.

I left the Coop Op that day with a sunburn, an onion, and some secondhand clothes, having gardened, watched a yoga class, participated in a workshop on food policy in America, and held someone’s baby for a few hours. I felt the thrill of having done manual labor outside on a nice day. I wondered, though, if an onion and a dress would sustain me if I relied solely upon the garden for produce. As communities continue to organize around gardens and sustainability projects, they must reckon with obstacles from weather to advertising. Even community gardens are not always accessible.

When I asked Reverend Ellis why this could be, he explained, “The top priority for us [the Greater Englewood Garden Association] is to create green spaces and ensure the health of the plants and the soil.” A garden is many different things, he told me, with produce distribution only one among dozens of goals.

Not everyone may have the time, inclination, or ability to trek over to a garden and tend to their own produce. Those working on the other side of produce distribution in Chicago understand this. They are the delivery services, brandishing convenience and carefully calibrated user interfaces. I talked to Thomas Parkinson, co-founder, Senior Vice President, and Chief Technology Officer of Peapod, in a location that certainly contrasted that of the Cooperation Operation.

In a sleek office in the Lyric Opera building in downtown Chicago, Parkinson and I nabbed a room with windows overlooking the city. I was expecting what he said first: “We mostly serve middle- to upper middle-class neighborhoods. We don’t really penetrate into the rougher neighborhoods.”

I asked Parkinson if Peapod targeted a certain demographic. He tapped his thumb against the table, then replied, “When you make deliveries, it’s across-the-board demographics. Single moms working two jobs, disabled people, old people, we deliver to all that. Our biggest market, probably, is working professionals, but if you ride on a truck I think you’d be amazed at who we’re delivering to.”

What surprised me were the quiet efforts Peapod has made in recent years to engage locally with food distribution. “We’ve made several attempts to break into the food desert. We did one thing where we created bundles of fruits and we delivered them to a community center in the Lawndale neighborhood,” Parkinson said. “People could then come and buy it from the community center, it was even subsidized. We tried—there just wasn’t much demand.”

When that effort failed, Peapod made another attempt, working with local activists Chris and Sheila Kennedy and their new community-based nonprofit, Top Box Foods, again delivering produce to churches, community centers, and the Alderwoman’s office, so that community members could access fresh food even if they didn’t shop for food online. Peapod originally did most of the fulfillment for the organization, but it now runs on its own.

Recently, Top Box Foods, Evanston-based tech company FarmLogix, and an Indiana farming hub collaborated to win the Food to Market Challenge. The challenge, part of a partnership between Kinship Foundation and Chicago Community Trust, awarded $500,000 to the partners to support their plan to sell boxes of produce from Chicago Public Schools for an affordable price—between eight and twenty-eight dollars. In an article from the Tribune, Sheila Kennedy said she “expected Top Box to deliver the equivalent of 160,000 meals per month, up from about 40,000 a month currently. The boxes…can be purchased with LINK cards, the modern-day version of food stamps.” Their solution relies more heavily on networks and far-reaching distribution than on local community efforts, like gardens or farms. As the project takes off, their approach will be tested.

Peapod is supportive of both the networking and the local approaches. In 2015, Peapod announced a partnership with Gotham Greens in the Midwest. Earlier that year, Gotham Greens’s newest greenhouse, one of the world’s largest and highest-efficiency rooftop farms, opened in Pullman. Hyperlocal produce from urban farms across Chicago will now be available to Peapod shoppers from Chicagoland, Milwaukee, and Indianapolis. And for the past two years, Peapod has partnered with Harvest Moon Farms in Wisconsin to put together a summer Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA) Boxes, delivered weekly to shoppers for thirty-five dollars a box.

Speaking with the leaders of these efforts, I had nothing but hope that healthy eating could become widespread and indiscriminate. When interviewing community members, however, I realized equitable produce distribution faces fierce nemeses. Food deserts are linked to entrenched issues of politics and civil rights. In Chicago, food deserts disparately impact African-American communities, especially when considering the racial segregation of the city’s housing. But the biggest challenge to produce distribution is actually a practical paradox: profit and sustainability run counter to many of these efforts.

“The problem,” Parkinson said, “is just that we’re a private company that’s trying to make money.” Delivery services like Peapod may not be able to expand to the neighborhoods in Chicago that need produce the most—it’s simple supply and demand.

Big companies may face issues of profitability, but community gardens are not without their own problems. Nerat is planning to release instructional videos online, in addition to the workshops offered on-site, because damage has been done to Cooperative Operation crops by people who don’t know how to harvest them properly. It’s hard to toe the line between accessibility and responsibility. A similar community garden on 27th Street in Little Village, Semillas de Justicia, is gated and locked with a code. From the outside, it looks foreboding.

Just over on 26th Street, Guadalupe, a first-generation immigrant, sells mangoes to customers who drive up in cars, right outside of a local supermarket. When I asked if he knew about any of the several community gardens in his neighborhood, he responded, “I don’t think there are any. There are in Mexico. But here, no. Here, it seems to me, they don’t. Because we’ve looked into it, and have yet to find any. While there is support from the government for those who were born here [in the US], but for us, we who are undocumented, no.”

I asked if his shopping habits changed since he moved to Little Village. “Yes!” he told me, enthusiastically. “We were from a rancho. On the rancho we cultivated corn, all kinds of vegetables, beans, chilies. All of that, we grew in the countryside. We had large plots where we cultivated everything. Here, we shop in the supermarkets, wherever it is least expensive.” I asked if the same vegetables tasted different depending on where they were grown. “Yes,” he said, “only the things cultivated in Mexico don’t have many chemicals. But the things grown here [in the US] are. It has a lot of chemicals because in two to three months, they make the fruit to grow a lot, but in Mexico they don’t. It’s different.”

Another Little Village resident, Ignacio, worried about the quality of supermarket food as well. “Growing food at home and having it grown elsewhere is not the same,” he said. Even the chilies taste different to him, “maybe because of the fertilizers or because of the chemicals they use, who knows. But I think it’s that.”

The difficulty is not in creating new gardens, it’s in spreading the word that community gardens exist and are available to all community members, even the undocumented or non-English speaking ones. There are four community gardens in Little Village, all of which operate efficiently and offer plots of land and educational classes. They are run almost exclusively by locals. But Reverend Ellis insists, at least for Englewood, “As far as day-to-day gardening goes, it’s not going to be a good garden without accessibility.”

It’s surprisingly frustrating to hear the eager optimism of the various champions of Chicago produce, like Nerat or Parkinson, contrasted with the skepticism of those who don’t see community gardens as realistic solutions for themselves, like Guadalupe or Ignacio. “There are so many urban farms in Chicago, and anyone can do this,” Nerat insists. “We knocked on doors and got over 200 signatures on a petition, we gave a presentation to the alderman, and we got access for five years. People think this seems like a crazy thing, but you just need a vacant lot, a bunch of seeds, some good soil, and friends.”

To Guadalupe and others, those simple ingredients are so difficult to obtain that they are prohibitory. Guadalupe said that during the summer, many people grow food in their yards. But he was insistent that “if there was a larger plot, it would be better.”

Maybe what we need is just a little more hope. The innovations at Peapod, the wide-eyed courage of the Cooperation Operation—efforts are coming up from hyper-local community efforts and down from big corporations, each benefitting a population that doesn’t use the other. Nerat taught me that lasting change can start anywhere.

“If we can just change the way we look at resources, not just food, like bike wheels becoming a dome or old boats being used for planters…” She trails off briefly, perhaps recognizing the magnitude of the challenge. But she blinks and is hopeful again. “We have this one-time use way of looking at the world, but we take that old thing and we give it a new life. People get overwhelmed thinking about these big global issues. But it starts with one person doing something like this in their backyard and just changing the way they see things.”

Sam Baste and Elizabeth Ortiz contributed Spanish translation and additional reporting.