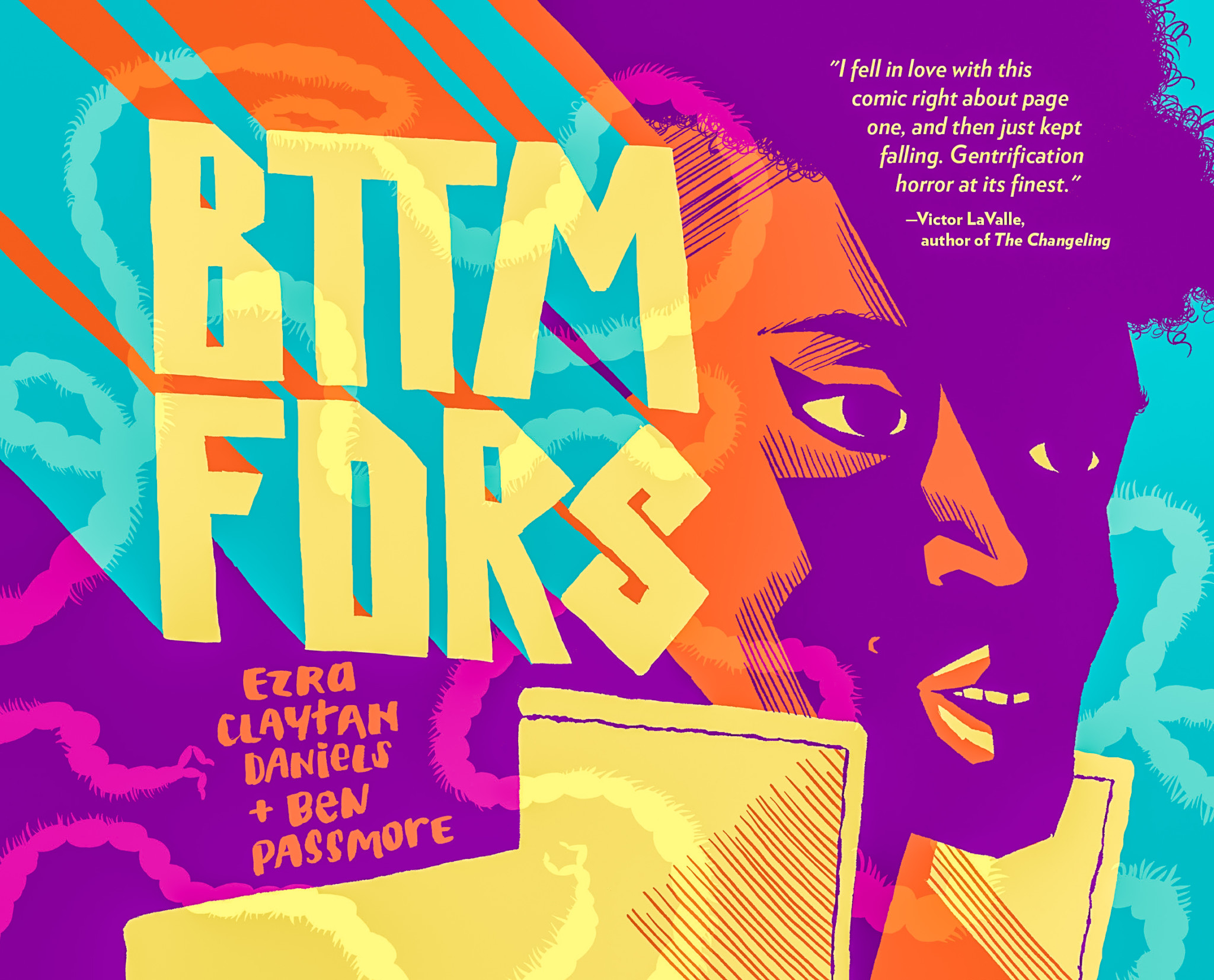

BTTM FDRS, written by Ezra Claytan Daniels and illustrated by Ben Passmore, an Eisner Award-nominated graphic novel published by Fantagraphics in 2019, was named one of the best books of 2019 by the Chicago Public Library. It unfolds in the fictional South Side neighborhood of Bottomyards, where gentrification and cultural appropriation encroach and mingle with more supernatural threats. Daniels’ storytelling and Passmore’s illustrations make for a cinematic, politically urgent take on classic horror tropes. The Weekly sat down with Passmore and Daniels for a Zoom interview in late May to talk about their collaboration, future work, and what BTTM FDRS has to say about our current political moment.

How are you doing? It’s a strange time, everyone’s inside, we’re in a pandemic—what are you thinking about and working on during quarantine?

Ezra Claytan Daniels: It’s a surreal time, and it’s only gotten more surreal in the past week, with the police murders and ensuing protests. I can’t even wrap my mind around how things are changing, how things are being affected, and what to do. When everyone’s in quarantine, you feel so disconnected from world events. I’m staving off going numb as a defense mechanism and working to find ways to use art intentionally to stay engaged with the world.

One thing you two have talked about in other interviews is using art as a processing mechanism. How did that figure into the creation of BTTM FDRS and into your creative process more generally?

ECD: My work has always had a political agenda, but as I get older and more experienced, I’m starting to be more intentional about how I incorporate politics into my work. I think BTTM FDRS was the beginning of that, in that writing it was a very therapeutic process. To me, it was about reconciling my role as a gentrifier, as a person of color who’s living in gentrifying spaces, a person of color who benefits from the privilege of passing as white in many situations. It was cathartic, it was therapeutic, and it was a process that led me to be even more intentional in how I incorporate politics in my work and into the stuff I’m working on now.

Ben Passmore: Yeah, absolutely. BTTM FDRS was cathartic. Something I love about BTTM FDRS is that it talks about everyone’s complicitly, including my own—It’s a clear-eyes investigation of how many of us take part in the colonization and co-option of our communities. The time for catharsis is over and has been over, in a lot of ways. It’s time to very methodically figure out we’re going to be different. That’s another reason I was really excited about the book before I drew it. It’s not a “woe is me” book. Ezra and I talk about this all the time—we’re two mixed Black men who lived in our communities. We have white adjacency and experience acceptance from white art people, and I was really excited to be a part of a conversation about our role in this.

Your main character, Darla, is an interesting character in that regard. She has the privilege of family money but simultaneously puts up with racism and violence at the hands of white privilege throughout the book. Do you like Darla? How did you decide to build her up as a protagonist?

ECD: Darla’s a conundrum in that she suffers at the hands of oppression but also benefits from certain privileges that her family has gained within that system of oppression. She was raised within an affluent suburb and has the privilege of that proximity to whiteness, but now she’s trying to get closer to her Blackness and explore her roots. That’s something I really identify with. I’m half-Black and half-white, and I think a lot of what I’m trying to do is flailing to reclaim the Blackness that I’ve been distanced from by being raised in Iowa, largely around white people. I really gravitated to Darla’s story, because she embodies a lot of the conflicts that I feel.

And positioning her within a world of body horror and gentrification horror is an interesting choice. Going into the book, did you have that genre and setting decided upon? Did you have an idea about what classic genre tropes you wanted to reject, replicate, or satirize?

ECD: I love body horror and science fiction, and I’m inspired by the history and tradition of hiding political messages in science fiction and horror—using genre as a Trojan Horse. During the process, though, I realized that those genre trappings may not be necessary. I became disenchanted with using a Trojan Horse to disseminate these ideals, because it’s too easy to obfuscate your intent and for people to take the wrong message if it’s hidden in all these layers. I think of something like X-Men. People constantly hold up X-Men as a metaphor for the Civil Rights movement, saying that mutants are Black Americans and that Professor X is MLK and Magneto is Malcolm X—people love to talk about that metaphor and how progressive Marvel is. But when you look at the X-Men, they’re almost all white people, led by white men. It’s too easy to look at that universe and have the message be that it’s white people who are oppressed, or that the impetus for oppression isn’t race, especially when they live in a fictional world in which Black people also exist…Moving forward, I want to make work that plays in these genre sandboxes because I love them, but which doesn’t obscure the political message.

How does that connect to what you were saying about working on mainstream shows and trying to get political messaging in there, but have it feel intentional?

ECD: There are a lot of metaphors in BTTM FDRS that sometimes hide its ideology, but there are also more explicit parts. Two conversations happen in BTTM FDRS that are really on the nose—one in which Darla’s arguing with Cynthia about white privilege, and one in which she’s arguing with Julio in the bar. These are really pointed conversations that I have with my friends about racism and gentrification and cultural appropriation, and I included them as the keys to the political message of the whole story.

A major theme of that scene in the bar and of the book more generally is authenticity and irony. How do those ideas interact with your exploration of gentrification in BTTM FDRS?

ECD: I set out to write a book about gentrification, but as I began to work on it the parallels between gentrification and cultural appropriation became more and more apparent. The system of gentrification is really complicated in a way that cultural appropriation isn’t so complicated. For example, I live in an affluent Black neighborhood in Los Angeles that’s gentrifying really fast. It complicates the issue in a way that I didn’t want to delve into with BTTM FDRS specifically, so I found it easier to wrap it in a metaphor of cultural appropriation. Using cultural appropriation as a symbolic framework was the path that seemed cleanest to me, and I did that using hip hop and rap specifically. The character of Julio is, as I said before, one of the keys to the puzzle in that he is really the confluence of all these things—cultural appropriation, gentrification, authenticity, and irony.

[Get the Weekly in your mailbox. Subscribe to the print edition today.]

The story takes place in Chicago, but you’re from L.A. Is it right that the Bottomyards is based on Back of the Yards?

ECD: It’s named after Back of the Yards, but the neighborhood’s probably more like Lawndale or Garfield Park.

So what role does Chicago play in the story? Could BTTM FDRS take place in L.A., or do you see the story as essentially Chicago?

ECD: I conceived of BTTM FDRS and wrote the first few drafts of it while I was living in Chicago, so it contains a lot of thoughts and experiences specific to my time there. Obviously, gentrification is an issue that’s affecting cities everywhere, and I’ve definitely seen things explored in BTTM FDRS play out in L.A. Ben was living in New Orleans at the time we started work on the book, and he lives in Philadelphia now. And Ben was a huge influence on the later drafts of the script, too.

Can you tell me a little bit about your collaborative process? Do you write the story first, or do the drawings come first?

ECD: I wrote the book in screenplay format and sent it to Ben. We’d met at comic shows in Chicago a few years before and hit it off, and were looking to work together…I love [Ben’s] work and have the utmost respect for him as an artist and cartoonist, so I sent him the screenplay without breaking it up into panels and pages. I wanted to give Ben freedom in the world to turn that into images, and he just ran with it.

BP: One of my favorite parts of our collaboration was spending a week at Ezra’s house doing an intense BTTM FDRS bootcamp. I slept on his floor, we ate all our meals together, we talked every day about what the book would look like. We listened to music and watched movies. Over the preceding two years of working on BTTM FDRS, Ezra hadn’t given me a lot of feedback, in part because I had a solid idea of what he wanted me to bring to the book visually and what he envisioned for it.

The colors from BTTM FDRS are so beautiful and page-filling and really create the mood of the book. How did you approach coloring the book?

BP: It’s two-fold. First, there’s the boring practicality of having to color a 300-page book. Ezra understandably told me we should probably not color BTTM FDRS because he wanted to see it before the year 3000. I’d been really inspired by a French cartoonist who did a limited palette. I like how a limited color scheme prioritizes mood and temperature and time, rather than having a more literal approach. I foolishly suggested that five colors would be as quick as, say, four gray tones—it absolutely was not.

Some of the coloring was to help the viewer recognize where we were in the world—if we’d changed rooms or gone somewhere else in the narrative. I wanted to express the idea that as gentrifiers, the characters were trying to create a home in a place that was not constructed for them to live. A lot of these gentrified places are not places where people are even supposed to live. The units in the book are constructed as weird pieces of poured concrete and you’re supposed to think “this is not a home—this is not an apartment.” In reading other horror comics, I was intimidated because I’d never done that before. I wasn’t sure my style would be spooky enough to sell scares, but I figured I should approach everything in my own way. I also felt like since I was coming [to] it with a goofier style, I should have everything be unexpected. Rather than going for classic horror gray and brown with blue shadows, I thought I’d hit them with something bright and unnatural.

In the past week we’ve seen the televisation, through social media, of brutal police murders. How does this wave of police violence, coronavirus, and other current events interact with BTTM FDRS? Are you returning to the book with new eyes at all, and how will current events guide future work?

BP: Well, I mean, the police kill Black people all the time. I remember growing up and hearing about Amadou Diallo. I’ve been Black my whole life. I leave the house and there’s a lot of potentialities—one is getting shot by the police. To me, there’s the creation of spectacle from these recent deaths—for example, in the case of George Floyd, we have a video that I didn’t watch, but I saw pictures of him being killed—that’s incredibly shocking. But this is America, and I’ve been in America basically my whole life. My work is the work that it is because of the spectacle of Black death and victimization. So in that way, it doesn’t change anything. Honestly, the thing that is significant to me is the amount of resistance being displayed in places like Minneapolis—that’s inspiring.

In my lifetime—I’m twenty—I haven’t seen police precincts being taken over by protesters before. What role do you think social media plays in the spectacle you’re talking about, in inspiring action in the wake of publicized murders?

BP: Most of the Black people in my life erased their Instagram for a little bit. They’re not interested in seeing these depictions of Black death, or the calls for humanity—the performative aspects of this. This is important for white people—not necessarily to see depictions of Black death, but to hear critiques of police at the system level, the history of white supremacy, the history of lynching. I don’t honestly think we need social media for this—for instance, in the Watts Riots, a violent, unjust police stop brought people into the streets. There were enough people talking about it and we had the same result. Communities will organize themselves. People are getting endorphins and virtue signaling on social media and as a Black person, who’s been arrested and experienced police almost strangling him, that’s not helping me.

Is there potential for another BTTM FDRS book? Is Darla’s story going to be continued?

ECD: We had some ideas for a sequel—there’s definitely more to explore, and I think it would be interesting to get more into the nitty gritty effects of gentrification. We were traveling to gather for something recently, and Ben and I had a long talk about what we’d like to do for a sequel. But like Ben was saying, BTTM FDRS was born in a time really similar to what we’re going through now. The rage we were feeling when we first talked about working on this together was in the wake of Alton Sterling and Mike Brown, and the feeling we are feeling now with public outrage at the public murder of Black bodies. I’m really proud of BTTM FDRS, but I think the work I’d want to make from those feelings now is different than the work I wanted to make five years ago.

BP: Also, as a Black artist, I don’t really want to make work about the inherent victimization of Black people. I also want to write stories about how we’re making things happen for ourselves. There’s an important history there—in my own work I like to read and write about Black revolutionaries. If you compare within just the Black Power Period—mid, late 60s and 70s—what happened to white radicals versus what happened to Black radicals, it’s amazing we have any Black radicals. That’s an important part of the story when talking about Black persistence and the hurdles we’ve had to overcome. I personally want to create inspiring stories, and not be part of creating content for the white gaze about Black death.

Ezra Claytan Daniels and Ben Passmore, BTTM FDRS. $24.99. Fantagraphics. 300 pages. (This title is currently out of print, but digital versions are available on Comixology and Google Play.)

Ruby Rorty is an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, where she majors in Economics and Environmental Studies. She is the head editor of the Viewpoints section at The Chicago Maroon. This is her first piece for the Weekly.