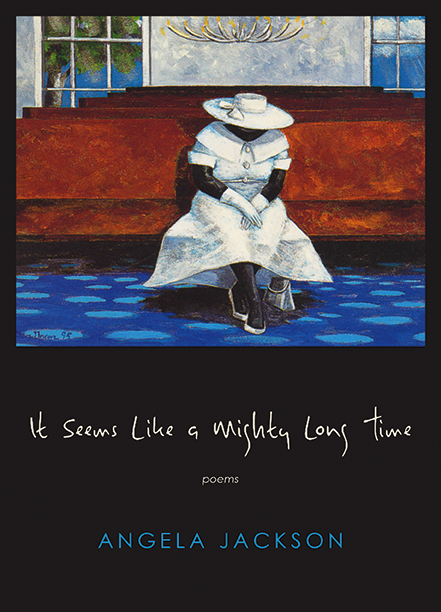

An organ opens sweetly—texturing the space of the song, accompanied by backup singers and other instrumentals—before the voice of Barbara Lewis, nineteen at the time of the initial recording in Chicago’s famous Chess Records studio, begins. It is from this song, “It Seems Like a Mighty Long Time” —warm, full, and nostalgic—that poet Angela Jackson fittingly takes the title of her newest poetry collection, which explores the intersection of emotion, memory, and politics.

On Saturday, February 21, the Logan Center for the Arts, the University of Chicago’s Arts + Public Life, and the UofC’s Center for Study of Race, Politics & Culture co-sponsored a party and reading celebrating the book’s release. In some ways, the event became a retrospective of Angela Jackson’s work and life more broadly, as a series of speakers emphasized the poet and playwright’s importance as a mentor for successive generations of black Chicagoans.

Speaking immediately preceding Jackson’s reading was Haki R. Madhubuti, a Black Arts Movement contributor and author. Madhubuti is the founder of Third World Press, the largest independent black-owned press in the United States, located in Chatham. He spoke to Jackson’s lifelong interest in creating and promoting black art; they met over forty years ago, when eighteen-year-old Jackson joined the Organization of Black American Culture as a freshman at Northwestern University. It is Madhubuti’s press that published Jackson’s first book, Voodoo Love Magic. When Jackson followed him onstage, she spoke fondly of the quintessentially Chicago arts scene that she has lived in: her forbears and her descendants together form what Madhubuti called a “cultural family.”

This interest in history and literary inheritance runs deep in It Seems Like a Mighty Long Time. The only titled section of the work, “Suite: Ida,” is named for Ida B. Wells-Barnett, whose journalistic efforts in documenting lynching in the Jim Crow South are refracted throughout the section’s poems, depicting a cultural landscape preoccupied with violence against black bodies. The poems also include repeated reference to Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruits”, the blues singer Bessie Smith, Gwendolyn Brooks, Aretha Franklin, and, eventually, W.E.B. Du Bois.

One way that Jackson engages with her predecessors is through their writings, most strikingly displayed in “The Smoke Queen,” a sharp response to Du Bois’s famous “Song of the Smoke” regarding gendered experience of race. She engages with the legacy of prior black creators, giving Gwendolyn Brooks a stirring eulogy (“Who can remember a time when your language / Did not dignify what or who was diminished?”). Neither does Jackson shy away from the private corners of cultural figures’ lives—one poem, “Did Ida B. Wells Ever Pass Bessie Smith on the Boulevard?” plays with the physical proximity of both women as an access point to the indignity Jackson finds in their deaths, each reflecting a “final violence.”

Jackson’s own family—her parents, cousins, nieces, and eight siblings—receive heavy attention in the first sections of It Seems Like a Mighty Long Time, and this composed the majority of the material she read at the collection’s release. Her voice curved over and across words, reminiscent of the blues, the trill something like Bessie Smith in her most famous recording, “Nobody Knows When You’re Down.” Jackson has a poet’s cadence, careful and sharp, that highlighted the lyricism of these visual and evocative reflections, particularly of “Perfect Pears” and “The Fabric of Our Lives,” each deriving power from the specificity of its scene.

That specificity speaks to one of the greatest strengths of It Seems Like a Mighty Long Time. The political—especially inequality rooted in gender and racial difference—is more than polemical. A strong indictment of “American Justice” (a poem in which Jackson harkens back to Maya Angelou by declaring as chorus-line “I sing because I am not free”) is so effective because it is rooted in the personal and concrete. The epidemic of young black men dying becomes the story of a student of Jackson’s, presumably from Kennedy-King College, where she taught until retirement. Flawed societal conceptions of rape are also illuminated in the image Jackson paints of uncomprehending observers on an “L” platform, giggling “at the sight of public sex” despite the woman’s “mouth stretched wide as the river she was drowning in.”

Perhaps most compellingly, Jackson cannot distance herself from the tragedies she notes—the scene of the rape causes her to ask, finally, “Did she look like me?” Another poem describes the aftermath of Emmett Till’s death with a particular interest in his mother, whom the speaker empathizes with: “How articulate was this wrecked flesh! / The remains of her boy, once beautiful. / Then ruined. / She left the casket opened.” The line between the mother’s sorrow and her own sadness blurs, pulling the reader into the grief, horror, and defiance. This is emotional honesty backed up in full by righteous anger.

Personal and collective memory intermingle freely in Jackson’s verse. In “Her Memory Coming Home,” the poet recalls a relationship as a “knot of time.” Jackson runs with this stance on the histories richly outlined in the collection, treating poems as individual threads entangled with other experiences, formative historical events, and literary predecessors. It is this knotted heart of the collection that grants it strength.

Though often lovely as individual threads, It Seems Like a Mighty Long Time gains power through its obsessive tangles—the constant revisiting of Mississippi, of Chicago, of Gwendolyn Brooks and Ida B. Wells, and our own “lopsided land:” fruitful territory for a collection of startling political and emotional poignancy.