Hundreds of nail holes pepper the dark-brown wood paneled walls of the repurposed 1920s brownstone. Each indentation serves as a kind of signature for every Black artist whose work has been exhibited during the eighty-five-year history of the South Side Community Art Center (SSCAC).

The windows of the cozy house’s Margaret T. Burroughs Gallery have been temporarily covered to protect the art lining the walls from light. It feels as though decades of history, celebration, and community are concentrated in the living-room gallery. It was here that Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks and famed Black novelist Richard Wright worked on their writing and photographer Gordon Parks envisioned how to arrange his newly developed photographs.

“ Seeing these holes in the wall, people often talk about microcosms—these possibilities of the past,” said Lamar Gayles, SSCAC’s archives and collections manager. “These holes show a lot of history in some ways but also the immense amount of artists that have haunted this space over the decades.”

As the country’s oldest, independently run, and continuously operating Black arts institution, the SSCAC is an anomaly.

In response to the Great Depression, the New Deal’s Federal Art Project (FAP) funded 110 community art centers nationwide. Only a fraction were located in majority-Black communities. The SSCAC is the only one of those that is still in operation.

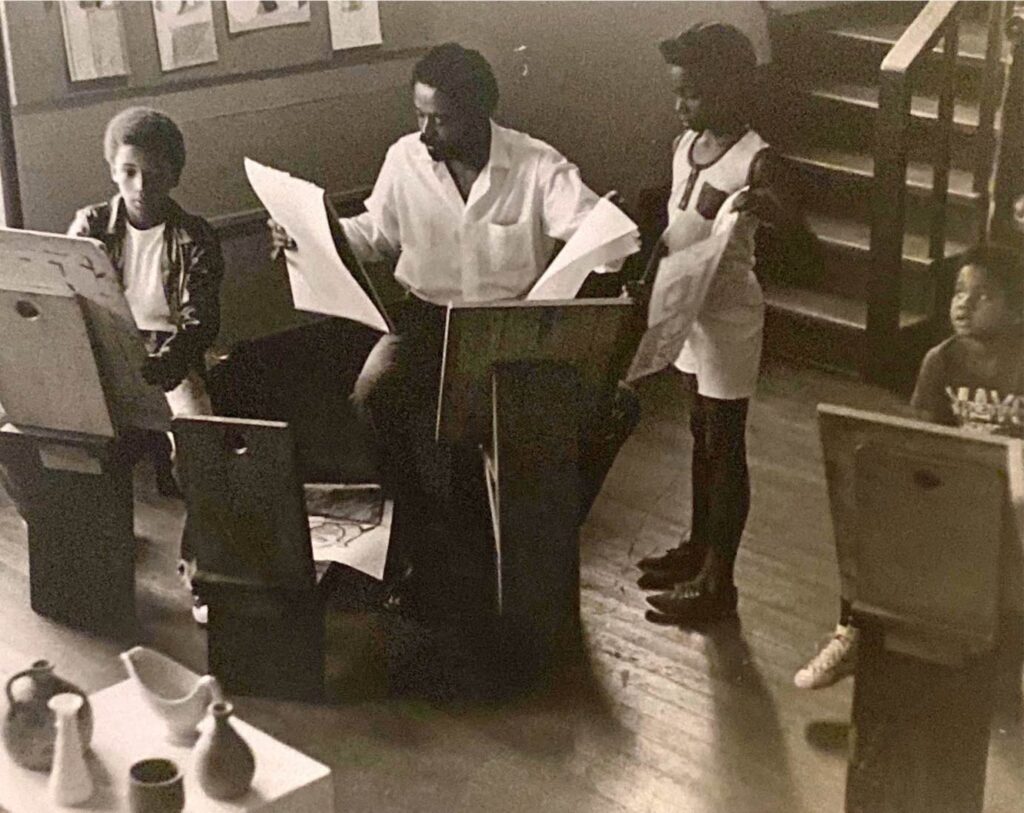

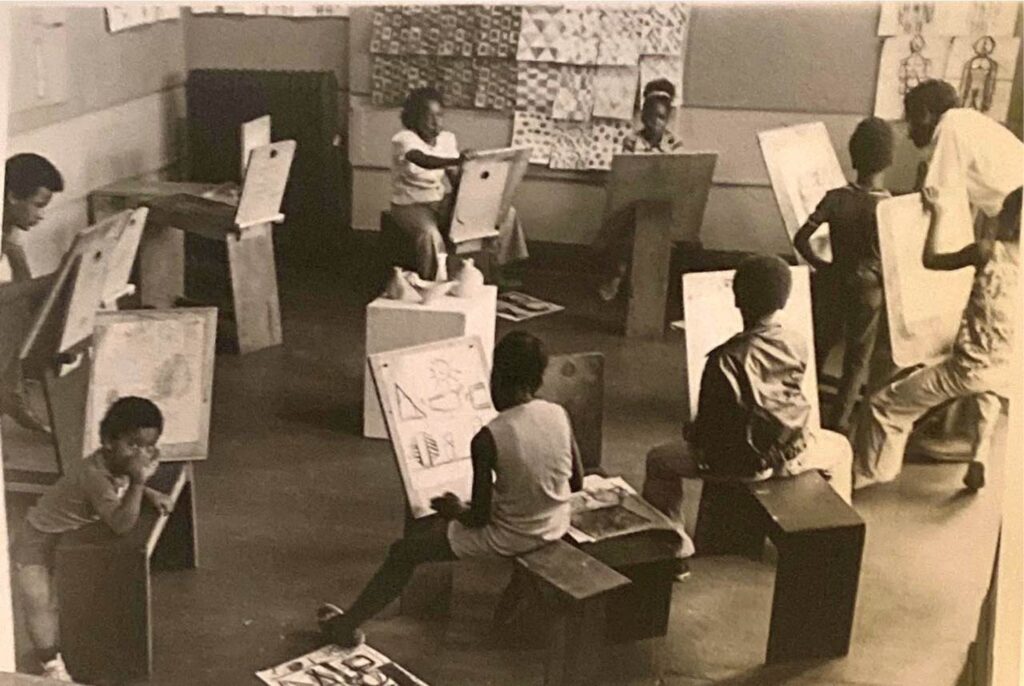

“The core to the mission of the Southside Community Arts Center is being of service to the community,” said Executive Director Monique Brinkman-Hill. “[It] has a history of filling that void and helping to make art more accessible to young people so that we do build our next generation of culture keepers.”

Despite growing disinvestment in arts and DEI initiatives, the historic art center is doubling down on its commitment to support Black artists and Black culture by pursuing a $15 million rehabilitation and expansion project. The environmentally responsive improvements will allow the SSCAC to reach new audiences, provide educational programming, and remain accessible to the community for decades to come. In the meantime, the center’s artists will have to contend with the space’s closure for over a year while the organization strives to leverage community fundraising to supplement foundation funding. Still, these challenges aren’t new to the center, which has relied on grassroots fundraising throughout its history.

On a quiet Saturday afternoon in February, a mix of Bronzeville residents, artists in colorful sweaters and expressive hairstyles, and folks in business-casual attire were scattered among the pews of Apostolic Faith Church. Unlike the religious Sunday services that usually fill the space, a lineup of architects, arts administrators, and real estate developers took turns at the lectern.

At the official community design unveiling, project leaders shared intricate details of the work, which will begin construction of the addition and rehabilitation of the historic house in the latter half of 2025.

With SSCAC’s status as a Chicago Landmark and a designated National Treasure by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the best option was a rehabilitation and expansion approach to increase functionality while keeping the original building intact. Due to the building’s age, the design team chose what the National Park Service defines as “Rehabilitation” to ensure the building’s structure is preserved while allowing for more adaptability in repairing and implementing new structures in the interior of the building.

With the guidance and support of Chicago-based development advisor URBAN ReSOLVE, SSCAC leaders sought out a team of diverse and local experts to complete the massive project.

The firms working on the project are Future Firm, an architecture and design research office focused on arts and culture organizations, non-profit facilities, and mission-driven businesses in Chicago, and wrkSHäp | kiloWatt, a Black-owned, woman-owned historic preservation and design studio. Both organizations are committed to balancing the preservation of SSCAC’s rich history with creating a modern, environmentally sustainable and accessible space. Their plans will add 10,000 square feet of space to the center, expanding visitor capacity by 398 percent and making the venue wheelchair accessible. The expansion will allow for more exhibitions, art practice space, archive storage, and gathering space for the community.

k. kennedy Whiters, the principal architect at wrkSHäp |kiloWatt, brings her expertise in architectural preservation and her own deep connection to the South Side to the project.

“I’m acutely aware of the importance of the archives [and] the legacy of Black people: We are the living archive,” Whiters said.

Growing up on the South Side and in the south suburbs, Whiters recalls her mother and maternal grandmother telling her stories about the impact and importance of Dr. Margaret Burroughs and other leaders during Chicago’s Black Renaissance in the 1930s and ’40s.

In the 1930s, a group of Chicago-based Black American artists, including Burroughs, crafted a vision and fundraising strategy for the art center. Burroughs was one of the center’s youngest members and brought her youthful passion to her fundraising efforts that included membership drives, benefit parties and lectures, and her “Mile of Dimes” street-corner collections that took place on what is now Martin Luther King Drive.

In 1941, Burroughs, Eldzier Cortor, Charles White, and Archibald Motley Jr founded SSCAC and purchased a vacant brownstone on South Michigan Ave. for about $8,000—or a little over $170,000 today. The deteriorating building was renovated the same year. Federal funding for arts projects, including for the SSCAC, was cut in 1943. Still, the center’s tenacious fundraising and devoted community enabled it to remain an active art center and community space.

The art center has acquired over $10 million in funding from city and state institutions, arts foundations and other private donors for the rehab project. SSCAC plans to close the $5 million gap through community fundraising, invoking the spirit of Burroughs’ “Mile of Dimes” efforts.

“With my heart and passion, I’m clear that this is going to happen,” Brinkman-Hill said. “Our community is going to make this happen.”

Whiters said she feels proud to have a chance to preserve the space that helped facilitate her culturally rich upbringing and to support the legacy of the critical Black community arts space.

“ I’m looking forward to neighbors and folks from the South Side walking through the space and the smiles and the awe,” she said. “[There will also be] an ancestors space to honor the legacy of our ancestors who pave the way for the South Side center to continue to be there in the future.”

Even the contract team—a joint venture between Brown & Momen, Inc. and Berglund Construction—is committed to prioritizing the surrounding community for employment and career development opportunities.

Toni Graham, the director of community initiatives at Berglund Construction, said her plan is to prioritize demographically diverse and neighborhood-focused recruitment for subcontractors so that “the people in the community can look like the people that are on the project.”

On the uppermost level of the 130-year-old brownstone, Lamar Gayles has spent many years working to preserve SSCAC’s precious artworks and archives. The storage rooms and closets on the top floor house the works of famed artists such as Elizabeth Catlett, Charles White, and Ralph Arnold, which are stowed away alongside film photographs and pamphlets from art center celebrations from the early mid-twentieth century.

Gayles has installed air conditioning units and utilized dehumidifiers to protect the precious, aging items from the rising heat of summertime and muggy days. Each art object is like a delicate elder he’s been tasked with keeping alive and well.

Gayles, who is the archives and collections manager at SSCAC, has been actively engaged with the center since he was a teenager. While working for the Museum of Contemporary Art in high school, he was a part of a small team that collaborated closely with SSCAC for an exhibition that exposed him to “a Black art historical canon” and the work of Black women artists like Geraldine McCullough. Upon graduating from college, Gayles continued to volunteer his time with SSCAC and eventually worked with the executive director to design a full-time role working with the center’s archives and art collection.

“Diversity, equity, and inclusion being targeted should [alarm] people to make sure that certain forms of information aren’t lost,” Gayles said. “In the same way like book bannings and book burnings really made certain information lost, I think we don’t want that to happen to Black culture.”

The challenges of this political moment aren’t new to the center, which struggled through the anti-communist moral panic of the Red Scare in the 1940s and ’50s. Black artists like Romare Bearden, Aaron Douglas, and Charles Alston, who used their art to express their political views around racial and social inequity, were flagged during the Red Scare as un-American. The social and political pressures of that moment led to internal tension and anxiety at SSCAC.

By the mid-1950s, even Burroughs felt the need to take a leave of absence from her work as a teaching artist at the center due to the paranoia present within the organization’s board. Upon her return, she was denied membership to the art center and only later re-emerged as a guiding figure in SSCAC revival in the 1960s. SSCAC experienced a major decline in the classes, exhibitions and social gatherings they offered during the Red Scare, leading the organization to drift away from its mission.

Gayles said he and his colleagues are intent on not allowing social and political repression dictate the art center’s work in the future.

zakkiyyah najeebah dumas-o’neal, the SSCAC’s previous public programs manager, worked closely with Gayles to co-curate exhibitions and support programming that also highlighted queer artists in the community’s archives.

For dumas-o’neal, it was important to expand what was already a “Black, affirmative cultural space” to be inclusive of all facets of Black identity. She said she believes the new accessibility improvements to the space will enable another level of inclusivity.

As we walk through the rooms where Gayles has spent many of his days communing with objects, the functional need for restoration feels just as clear as the aesthetic motivations—and more urgent. At the rear of the property, what was once a coach house and then a residency space now remains unused; the roof is caving in on itself. Inside, swatches of faded paint are peeling from the ceiling. Beloved objects are nestled close to each other, unable to be displayed in all their glory due to the limited square footage.

While the rehabilitation and expansion project will eventually provide ample room to display the art center’s extensive collection, for the year-or-so that construction takes place, the center will be significantly limited in its ability to accommodate visitors.

The SSCAC archive will transition to an offsite storage facility with office space for staff to work from. Because the space will likely be too small for visitors, Gayles plans to use this interim period to focus on increasing the archives digital accessibility to reach more interested individuals. His hope is to make the archive as resilient and accessible as possible.

“ I think doing all this, [building] an archive for the future, allows people to see possibilities,” said Gayles. “It allows an expansive realm of nuance in the past and it allows people to build a new kind of future for themselves.”

Gayles’s team has floated starting an oral history project during the renovation that centers the reflections of community members about SSCAC’s impact in their lives—making their voices additions to the museum’s archive.

It’s easy to imagine this active dialogue between the past and future coming to life in the new and improved space equipped with a solar-ready roof, an outdoor events space, and new gallery spaces.

Regardless of which part of the building this next generation flocks to, the legacy of past artists will reach them. Designed by the project’s architects, including Ann Lui of Future Firm, the historic pattern of nail holes found in the center’s wood panels will be represented through a perforated exterior wall plaque. Symbolically linking the past and present, sunlight will pass though the panel’s intentionally placed holes and create a unique pattern in the new exhibition space.

“We were thinking about the work of Margaret Burroughs and the way that in etching and printmaking, it is actually an act of subtraction that creates an image,” said Lui. “We’re really excited to share that the work, the legacy of the artists that came in the generations before will let in light for the artists in the generations to come.”

Jasmine is a writer, facilitator and community builder living in Woodlawn. You can learn more about her work at www.jasbarnes.com.