Dozens of community members, educators, parents, and students gathered at Mt. Pisgah Church at the corner of 46th Street and King Drive on April 14 to discuss the state of Bronzeville’s beloved Walter H. Dyett High School. Jitu Brown, education organizer for the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization, led the conversation and reiterated the struggle between community and city interests regarding public education.

In August 2015, Brown and other members of the Coalition to Revitalize Dyett staged a hunger strike that lasted thirty-four days in protest against Chicago Public Schools’ delays of discussions about the reopening of Dyett High School. Dyett was closed at the end of the 2014-15 school year. Today, old tensions with CPS have reemerged in the community as CPS readies the school for its grand reopening this fall.

CPS released a request for proposals for a new Dyett in December 2014, effectively reversing the decision to close the school indefinitely. The Coalition submitted a fifty-three page proposal for the Walter Dyett Global Leadership and Green Technology High School; the proposal called for an open-enrollment neighborhood school with a green technology focus and “community-based internships.” This proposal, as well as two others, were rejected. CPS announced on September 3, 2015, that the new Dyett would be a neighborhood, arts-focused school instead.

The Coalition continues to oppose the CPS plan, citing anxiety about the practicality of an arts-focused education in terms of job and higher-education prospects, as well as a more fundamental distrust in the district and its role in the larger project of neighborhood development. In an interview with the Weekly, Brown said that the disruptions of community institutions in Bronzeville—the closure of neighborhood schools like Overton Elementary, the takeover of schools like Phillips High School by outside organizations, the closure of police stations (like the 2011 shutdown of the Prairie District Station)—all read as a city-mandated “disinvestment in us.”

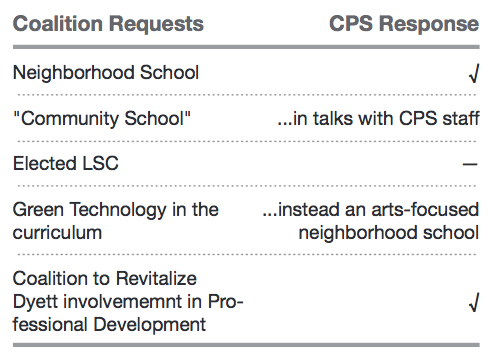

At last month’s Coalition town hall meeting, Brown described the five requests the Coalition has made for the new Dyett, what the school will offer, and how it will serve the community. The Coalition wants to include green technology programming in the existing science and math curriculum, as well as enable teachers from the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) School of Education and the citywide organization Teachers for Social Justice to lead professional development for the school’s new hires.

The Coalition also demands that the school be a “community school,” where the building itself would remain open past school hours for community use. The fight for Dyett, including the protests against the school’s closing and last year’s hunger strike, would be commemorated prominently in the building. The Coalition is also interested in developing an internship colloquium where students will work with local, national, and international businesses and organizations for two and a half hours a week during the school day. Lastly, the Coalition is dedicated to securing an elected local school council (LSC) within the first year of instruction.

Most of these demands have been either discussed or agreed upon in conversations between the Coalition and CPS. Those regarding green technology programming, commemoration and the colloquium (reimagined as a seminar with the opportunity for speaker series as well as off-site internships) have been more or less confirmed. According to McLoyd, both the UIC School of Education and Chicago Arts Partnership in Education will be providing professional development for the school’s new hires. The community school plan is still in talks. The only demand that remains untouched is the elected LSC; without that, full support of the school by the Coalition is doubtful.

“We’re pleased with the fact that we are having conversations [with CPS], but we are not satisfied until the things that we’ve asked for—which we believe is an enormous compromise—are honored,” Brown said.

Brown also told the Weekly that the Coalition has been in talks with several organizations and foundations to support the school both financially and academically. The American Federation of Teachers has pledged to provide funding for the school through its Innovation Fund. Furthermore, Amnesty International, the Annenberg Institute, the Advancement Project in D.C., and Equal Education in South Africa are all interested in providing internships for students as part of the aforementioned seminar programming; this support is not guaranteed, however.

“It’s contingent on what the community asks for being honored,” Brown said. “And we wouldn’t ask [the organizations] to support a school that we had no say-so in. That did not honor the wishes of the community.”

Enter Beulah McLoyd: Bronzeville resident, CPS parent, and former educator and administrator with the district. As the new principal of Dyett, McLoyd would “oversee planning and preparation at the school to ensure it is ready to provide a high-quality education to its students on day one,” according to the September 24 CPS press release announcing the hiring decision.

Since then, McLoyd has overseen staff hiring, middle school recruitment, infrastructure, programming, and curriculum in preparation for Dyett Arts’s opening this fall. She is also working with the CPS design team for the school, as well as two Technical Advisory Councils (TAC)—one for arts and one for technology. The former includes members of Chicago’s arts scene, such as ballet’s Homer Bryant, jazz singer Joan Collaso, and Theaster Gates of the University of Chicago, among others. TAC members act as consultants for McCloyd, answering questions regarding the specifics of arts- (or technology-) focused programming and curricula; in the end, teachers make final decisions regarding curriculum.

The school will offer five different pathways for the arts-based side of the curriculum: digital media, dance, music, theater, and visual arts. Students apply directly to Dyett Arts, but are not required to apply to a specific discipline. According to McLoyd, there are currently no caps on any of the options: students simply request whichever pathway they’d like during a meeting with their parents and the principal. Students will also take courses in the standard areas of instruction, like math, reading, and history, alongside courses in their chosen pathway beginning in grade nine. Starting students in the arts curriculum as soon as they arrive enables them to receive “a well-rounded, in-depth experience,” rather than the two years of arts instruction they’d see in other schools, according to McLoyd. Advanced Placement (AP) courses will also be offered at the school.

The school will offer five different pathways for the arts-based side of the curriculum: digital media, dance, music, theater, and visual arts. Students apply directly to Dyett Arts, but are not required to apply to a specific discipline. According to McLoyd, there are currently no caps on any of the options: students simply request whichever pathway they’d like during a meeting with their parents and the principal. Students will also take courses in the standard areas of instruction, like math, reading, and history, alongside courses in their chosen pathway beginning in grade nine. Starting students in the arts curriculum as soon as they arrive enables them to receive “a well-rounded, in-depth experience,” rather than the two years of arts instruction they’d see in other schools, according to McLoyd. Advanced Placement (AP) courses will also be offered at the school.

Because the former Dyett was a neighborhood school with no particular focus, several changes to its infrastructure are in the works. A dance studio, a digital media lab, a visual arts studio, and a black box theater will all be added to the existing building in order to accommodate the new programming.

In addition, an Innovation Technology Lab will be established within the Dyett building; the Lab, a collaborative project with both the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) and DePaul University, will be open to Dyett students, but will ultimately function separately from the school. Instead, it will act more as a community hub for digital technology. The technology TAC includes Gerald Doyle of IIT and Dr. Nicole Pinkard of DePaul. According to McLoyd, the Lab will provide coding classes for area middle schools, and will also house professional development workshops for teachers.

Based on outreach and recruitment from elementary schools in the area, McLoyd notes that the students she’s spoken to are “extremely excited” about the programming at Dyett, especially the arts focus of the school. After visiting Burke Elementary to campaign for the new high school, she said, she received twenty grade nine applications from a single class of Burke eighth graders.

McLoyd views the district’s decision to reimagine Dyett as an arts rather than a green technology school as a positive choice for the neighborhood. In an interview with the Weekly, she cited a 2014 study by Adobe that ranks creativity as a skill set that employers actively seek out. According to the study, sixty-seven percent of surveyed hiring managers agreed that creativity was a foundational goal for success in their respective industries, and “creativity and innovation” have gained significant influence in salary increases in the last five years.

“It’s not necessarily about teaching a student how to dance,” McLoyd said. “But it’s also about those other skills that are not necessarily presented at the forefront. If I can teach a student how to think creatively, I can teach them how to create a job, and I can teach them how to get a job.”

Aspirations of college readiness for graduating students also informed many of the curriculum and programming decisions regarding Dyett. The school is offering an “early college pathway,” where students can take their first AP course, Human Geography, during freshman year. Students can also take an additional geometry course the summer after freshman year, enabling them to take five math courses in four years. Students will also be able to take courses at Harold Washington College as part of this rigorous academic pathway. McLoyd notes that this college-preparatory system works particularly well with the school’s arts focus, resulting in well-rounded high school careers for all students who attend.

“It’s a myth that we’re not preparing kids for college, because we’re providing a holistic, well-rounded education that to me, in my mind, prepares kids even more for twenty-first century work.”

It is currently unclear how many applications to Dyett for the 2016-17 school year have been received from within the school’s attendance boundary versus the rest of the city. According to Brown, although students from Bronzeville are applying, “a great deal more” of the applications are from outside the boundary.

On the other hand, McLoyd says that most of the applications are coming from the Bronzeville area, but not necessarily from within the formal attendance boundary or a “preferred attendance zone” created by CPS. Because Dyett will be a neighborhood school, students within the boundary are not required to apply as out-of-boundary students are—this allowance may help to explain the discrepancy. CPS did not respond when contacted for clarification on this question, as well as the definition of a “preferred attendance zone”.

So the question remains for every party invested in Bronzeville’s public education system, and the viability of Dyett as a neighborhood school: if enrollment proves to actually favor citywide applicants rather than those from the Bronzeville community, what will happen to the Coalition’s dream of creating a public school system sustained by the community itself?

“If Dyett does not work, we view it as further disinvestment in the quality of life and the basic quality of life institutions of a particular population of people,” Brown said. Disinvestment in the community comes in the form of school closures and turnarounds, but it has also compounded the closure of other institutions like police stations. For Brown, this is a human rights issue.

“Where do our children go?” Brown asked.

For now, Dyett’s development continues to move forward. The Coalition, despite their misgivings regarding the new school, are open to conversation with CPS and the Dyett leadership “as we’ve always been,” Brown told the Weekly. But without cooperation between CPS and the Coalition, the fight for Dyett—ultimately a fight for community-driven investment in Bronzeville schools—will likely continue.

“What we want to see is a solid K-12 system in our neighborhood,” Brown said, “and CPS cannot do that without the community.”