On a typical cloudy weekday morning, lines of cars roar up and down Ashland Avenue, bunching up at intersections with bikes and CTA buses as their users wait to continue their halting journeys through the city. But this major artery in Chicago could have looked a lot different, had a project proposed ten years ago last month been implemented then. That project called for a radical overhaul on Ashland to make way for a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system with designated bus lanes. The overhaul never happened, but the idea still has the potential to shape the future of Chicago’s transportation network.

Billed as a low-cost but highly efficient transportation service, Bus Rapid Transit infrastructure is going up all around the country in major cities like New York, Oakland, and Pittsburgh. Public transit advocates, both the Johnson and Vallas campaigns, as well as Chicago’s Regional Transportation Authority (RTA), which is the regulatory agency that oversees PACE, METRA, and CTA, believe that increased bus rapid transit lines promote more equitable transit and connect long underserved communities with the city at large.

According to Peter Kersten, a principal planner with the RTA, “BRT is focused on minimizing a lot of the elements of riding a bus that contribute to how long it takes to get somewhere.” Kersten defines industry standard BRT as having five independent ingredients: a dedicated bus right-of-way, off-board fare collection, streamlined boarding, transit signal priority, and a roadway alignment that allows buses to move independently of car traffic.

Despite minimal BRT infrastructure and lines today, the political momentum required to adopt BRT appears to be growing. The idea has been taken up in limited capacity across the city and suburbs, and other lines are in development.

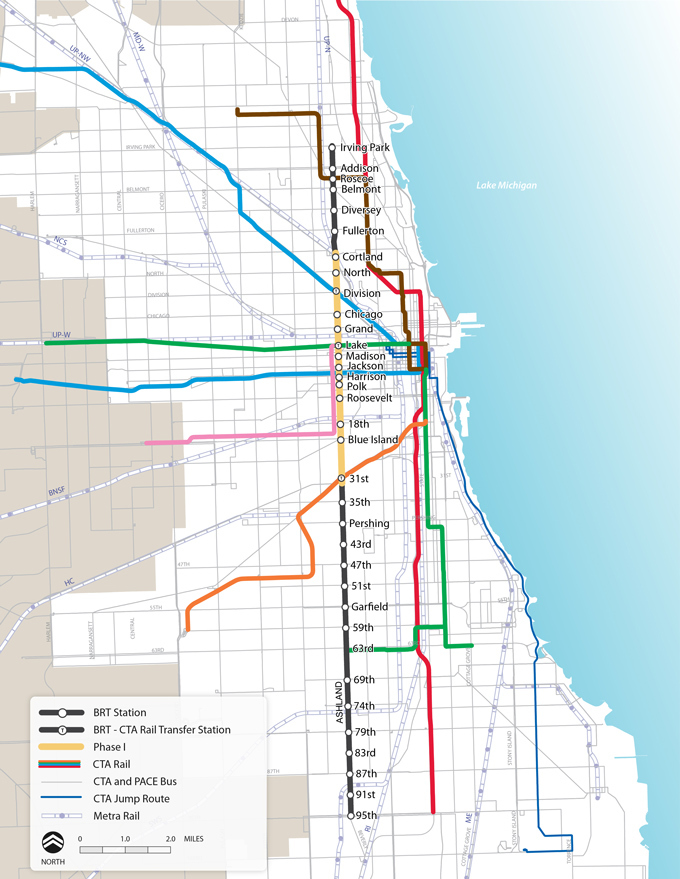

On the South Side, PACE is building out its PULSE services, which include some dedicated lanes and streamlined boarding along Halsted and 95th Street. CTA’s Jeffery Jump, which runs from Stony Island and 103rd to the Loop, also has limited rapid service and utilizes a bus-only lane for portions of its route. Downtown in the Loop, a dedicated lane exists for Loop Link.

These projects are “half measures,” said John Greenfield, a transit advocate and editor at Streetsblog Chicago, a blog that was founded in part to cover the Ashland BRT program.

To Greenfield, the reason BRT is necessary for Chicago is that its current transit system is inadequate and inefficient. “Chicago is a hub-and-spoke transit system,” he explained, meaning that the various train lines in Chicago are oriented around bringing the edges of the city downtown, like the spokes on a bike wheel that lead to the hub at the center.

“There is no reliable and fast transit that goes North–South except for the Red Line, which runs along the far east of the city,” Greenfield added.

The Ashland BRT project was supposed to remedy that, connecting parts of the South Side with little access to transit to the North Side.

The unrealized Ashland Avenue BRT project is an instructive way to understand just how the system could work. The proposed project involved the left lanes in either direction on Ashland becoming bus-only lanes, with boarding taking place at specially designed bus stations at the median at every half mile.

Planned as running from Irving Park Road on the North Side to 95th Street on the South Side, the CTA estimated the bus could travel at an average speed of sixteen miles per hour, nearly double that of the average CTA bus on Ashland.

Buses would have been extra long, with an added section on the back and three sets of doors. Users would pay before boarding as they entered the station, just as they do when getting on a CTA train, and thus be able to enter the bus at any of its three entrances instead of queuing at the front. The median stations would have been level with the bus so that the bus wouldn’t need to kneel down for riders who have limited mobility. Finally, the project on Ashland proposed transit signal priority, meaning that signals at intersections would extend a green light if a bus was nearing and give a bus priority if it was waiting at the light.

For Greenfield, Ashland BRT was about equity, “connecting neighborhoods that have historically been left out of Chicago’s spoke-and-hub railways and allowing people to access medical, educational, and professional opportunities across the city without having to own a car.”

As with any plan that has the potential to dramatically change existing norms, BRT has its fair share of critics, who point to drawbacks: losing car lanes, parking, and, in some instances, turn lanes. On Ashland, for instance, many left turns would be eliminated as they would interfere with the dedicated bus lanes.

Greenfield believes the project is all but dead, stalled as soon as it faced opposition from business groups along Ashland. Property owners also worry that car traffic will be rerouted to smaller residential side streets.

Asked for comment on the status of the Ashland BRT project, the CTA in a statement responded that, “BRT along Ashland remains a potential future concept, but additional public outreach on the design would be needed before advancing it further.”

All five of the BRT elements need to be present, in order for them to travel at the “rapid” speed advertised. And according to Greenfield, Chicago needs to commit soon as “peer cities like New York and San Francisco are far ahead in BRT implementation.”

That may be changing. Just last month, the RTA, approved its five year plan, “Transit is the Answer,” which calls on its agencies to build more transit-friendly streets and bus rapid transit (BRT) in the Chicago region.

While the RTA does not have any direct control in implementation, it “sets long term goals” for the agencies it supervises. Facing a $730 million dollar fiscal cliff in 2026, the RTA’s plan emphasizes the need for increased bus transit, which, unlike rail transit, has retained ridership at much higher levels since the advent of the pandemic.

And regardless who becomes the next mayor, both campaigns dedicate part of their transportation plans to expanded BRT. On his campaign website, Brandon Johnson advocates that “bus rapid transit (BRT) be expanded and fully implemented across key corridors in Chicago.”

A potential Vallas administration would “institute BRT lanes and lines to improve and speed bus service and to prioritize them to connect historically disinvested transit isolated communities.” Asked multiple times for comment, neither campaign provided more details about potential corridors for transit in Chicago.

As it stands, the city has streets that largely prioritize car traffic over bus, bike, and walking travel. Attempting to change that dynamic can and has been a challenging political battle for the city. That both campaigns, despite their well-publicized differences, profess a commitment to BRT is for Greenfield a mixed bag. “It’s encouraging to see it as a talking point. But I am not sure either candidate realizes that implementing bus rapid transit takes a lot of political courage,” he said.

Ashland Avenue, with eight CTA and one METRA stations along its route, remains a compelling potential home for BRT. And while BRT is not currently a prominent feature of Chicago’s cityscape, it has the potential to be. If advocates are to be believed, it is a mechanism to bring the city’s South and North Sides closer together and reimagine how transit works in Chicago, creating a safer and more equitable city.

Matthew Murphy is a barback living the dream in Chicago. This is his second story for the Weekly.

Great idea. Would be a sensible policy priority for a new mayoral administration that’s trying to solidify political support.

Way overdue. Chicago ranked as the city with the most traffic in the USA. Businesses don’t have the same data as experts at CTA. All metrics point to increased economic outcomes along BRT corridors. It would also take cars off the road putting more money in peoples pockets. Enough of this chicken little argument that if you change the way things are everything will come crashing down. We know transit works lets do it already! Driving is making people angry and miserable enough!