Every year, nonprofit advocacy group Preservation Chicago releases its list of the city’s most endangered buildings. The 2016 version featured three buildings on the South Side: the Lakeside Center, the Washington Park National Bank, and St. Adalbert’s Church in Pilsen. The Weekly photographed each building, and wrote a short history of the former two buildings. Stay tuned in the coming weeks for a longer feature on St. Adalbert’s.

Lakeside Center

Jutting out onto the Lakefront Trail, the Lakeside Center has been an integral part of the McCormick Place Convention Center since 1971. Designed by Gene Summers and Helmut Jahn, it replaced the previous convention building that was lost to a fire in 1967. Summers and Jahn were both students of the architect Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe, whose concepts of open design and transparency are present in the Center’s architectural design: large glass windows surrounding the entirety of the building, large steel support structures that give the building a sense of openness and a sleek, all-black aesthetic. Currently the oldest section in McCormick Place, the building is a mid-size exhibition space featuring the Arie Crown Theater, a 4,249-seat theater space.

The building was an important architectural contribution to the city of Chicago in the sixties and seventies, next to other famous structures like the Willis Tower and the John Hancock Building. But nowadays the Center doesn’t see the same amount of traffic it once did, due to the westward expansion of McCormick Place. Furthermore, the once expansive inside space has been partitioned into smaller venue space by the insertion of a permanent physical divider. The changes have left some city officials and investors questioning the importance of keeping the Center around. For instance, an alternative city plan for the now-relocated Lucas Museum of Narrative Art involved the removal of the Lakeside Center, but the museum gave up its plans for the city before the alternative site could be negotiated. A source close to Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s administration claimed the museum would “expand green space on the lakefront, remove a larger building and allow a valuable addition to the museum campus.”

Other opponents of the Lakeside Center, like Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin, see it as a symbol dividing the northern and southern parts of the city. Inaccessibility by public transportation is also a problem; in attempting to visit and photograph the Center, the easiest way was via the Lakefront Trail.

Preservation Chicago’s solution to these problems is to adapt the space for new purposes, particularly since it’s used less now than before. Of its expansive exhibition halls, the group writes: “These could be repurposed for a variety of functions including Chicago’s most expansive and comprehensive field house, recreational center and cultural center—with the large glass rooms housing indoor tennis courts and basketball courts in natural daylight, along with a running track and other amenities.”

Another potential solution to the problem of inaccessibility—though probably not one that would be endorsed by Preservation Chicago—is the proposed Burnham Sanctuary, suggested by urban design group Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill, which would involve the demolishing the building and replacing it with a nineteen-acre parkland full of meadows, wetlands, and running paths. This design would also benefit the migratory bird population that has suffered from the construction of the building. The glass design confuses the birds, who then fly into the windows at full speed, leading to injury and death. A bird sanctuary was created directly south of the center in the hopes of reducing the number of injuries and deaths. (Eric L. Kirkes)

Washington Park National Bank

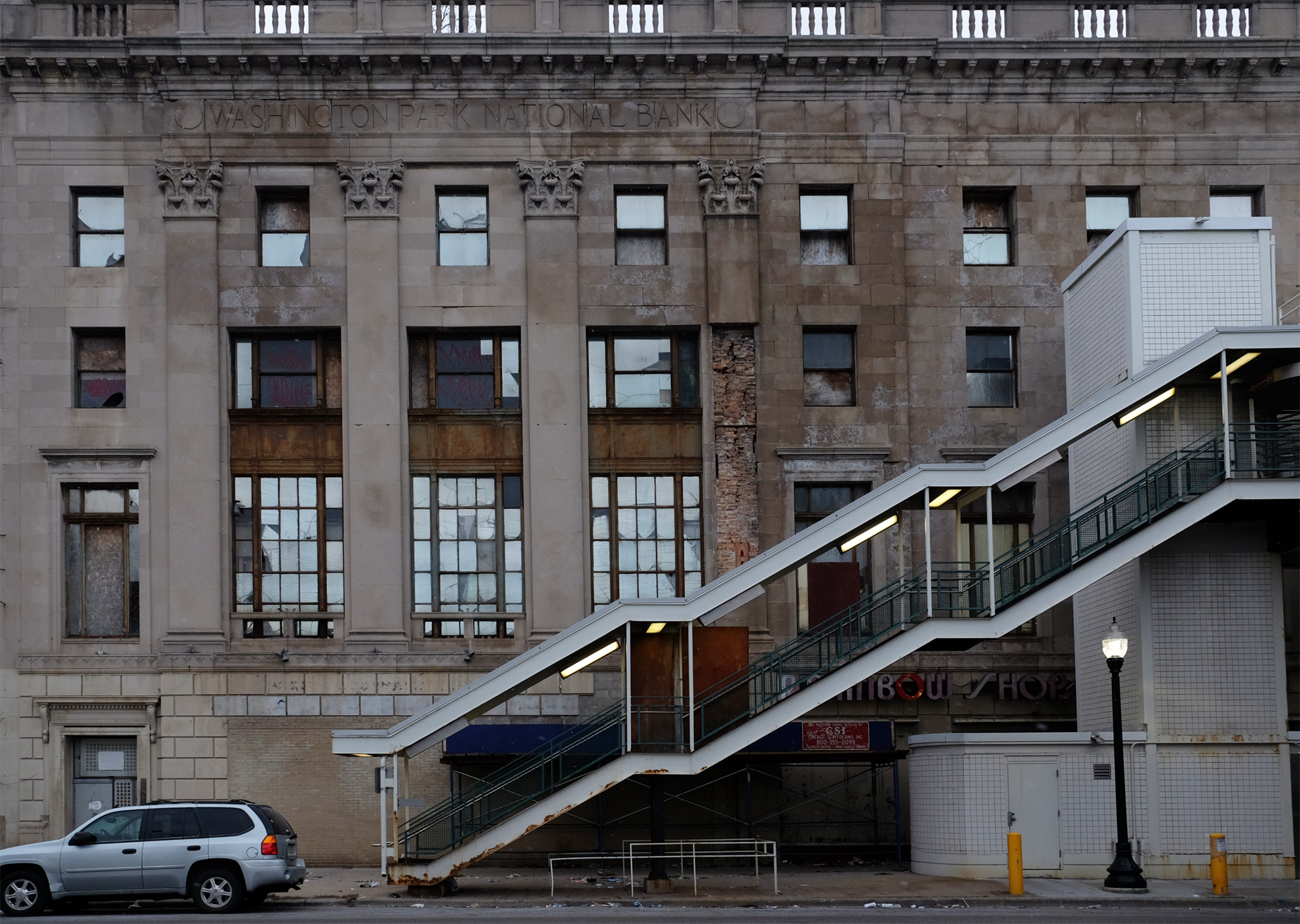

Located right at the intersection of 63rd Street and Cottage Grove Avenue, hidden behind the shadows of a stairwell up to the Green Line CTA Station, sits what remains of a once-magnificent bank.

In 1922, plans were drawn for a new Washington Park National Bank building to replace an older and smaller bank located a few blocks west at 63rd Street and South Evans Avenue. The original plans featured a classically designed building finished with white stone, fluted columns on the Cottage Grove side, and an elegant Bedford limestone elevation. There would be a forty-foot-tall banking floor and five floors of office space above, with the interior of the banking quarters ventilated by a flushed air system to keep bank patrons cool during Chicago’s hot summer days.

However, by 1923, plans for the bank’s design had completely changed. Instead of occupying the entirety of the first floor, the bank would share it with a large corner store and a row of four small shops, and the office space above would be limited to two stories instead of five. The building was finally completed in 1924 under the purview of architect Albert A. Schwartz with a budget of roughly one million dollars. Five other buildings at the intersection were also built within a few years of the bank.

The bank encountered financial difficulties in the summer of 1931, but W. H. Vanderploeg, the bank president at the time who went on to become the president of the W.K. Kellogg company, quickly formed a reorganization committee and reopened the bank as Park National Bank and Trust Company a few months later.

The bank changed ownership several times in the course of fifty years, but as the composition of the neighborhood changed, the bank was abandoned and gradually fell into disrepair. Alongside neighborhood changes, broader shifts within consumer banking habits have left large, intricately designed corner banks like Washington Park National Bank behind. “Banks have transitioned from these grand celebratory halls to a box building in a strip mall with a drive-in teller,” says Ward Miller, executive director of Preservation Chicago. “It’s really not a celebrated experience to walk into a bank and be impressed by the architecture or the space anymore.”

“It’s a remarkable building that has fallen off of everyone’s radar in an area that’s seen a lot of disinvestment over time,” Miller reflects. Along with the recently redeveloped Strand Hotel (also at 63rd and Cottage Grove), Washington Park Bank was not listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the federal government’s official list of sites that are deemed worthy of preservation and could potentially qualify for reinvestment tax credits. Lisa DiChiera at Landmarks Illinois says that there are also no local protections, as it has not been coded with an orange or red building designation by the Chicago Historic Resources Survey, a city-wide inventory of buildings constructed before 1940.

Despite these roadblocks, the bank has been a part of community development dialogues among organizations like 1Woodlawn, Blacks In Green, and the Bronzeville Community Development Partnership, among others.

“Right now, 63rd and Cottage Grove is a major stop because this is as far east as you can go on the Green Line,” says Paula Robinson, president of the Bronzeville Community Development Partnership. The bank’s location near the CTA station would give developers access to traffic counts at the intersection, which could make the case for stores like Walgreens or PNC Bank to move their business into the corridor and could give community organizations access to Transit Oriented Development funds.

“This is the only original corner building that remains at the intersection of 63rd and Cottage,” remarks DiChiera. “The other three corners, well, one is vacant, one is a liquor store that looks like it was built in the seventies, and the other is part of a strip mall. I’d hate to see the bank building go.” (Amy Qin)

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.

Glad to hear about these plans to redevelop this building where I met my wife.