The Underground Railroad was neither a railroad nor was it underground. It was a secret network led by people that included free Black and anti-slavery white people who helped escaped slaves, or freedom seekers, travel north for the promise of freedom. Along the way, they were offered shelter in secret hiding places, small amounts of money on occasion, clothing, and food.

Many of the trails fanned across Illinois and into what is now the south suburbs of Chicago. According to Larry McClellan, a historian and retired professor who has researched and published on the subject, “ten to fifteen percent of the activity of the Underground Railroad came through Illinois, literally through our backyard.”

Despite the region’s significance in the Underground Railroad, Illinois is rarely included in conversations about that history. McClellan and other members of the Little Calumet River Underground Railroad Project are leading the way to recognize and memorialize the places and people around Chicago who played a role.

Even though The Underground Railroad had nothing to do with an actual railroad system, railroad terminology was often used to confuse slave catchers and maintain secrecy. Terms such as stations referred to safehouses, passengers were freedom seekers, and lines were another way to indicate the roads being followed. Guides were known as conductors while trains and engines were covert references to farm wagons and teams of horses.

The Underground Railroad started at the place of enslavement and followed natural and manmade modes of transportation such as rivers, canals, bays, the Atlantic Coast, ferries, roads, and trails. According to the National Park Service, freedom seekers went in many directions—Canada, Mexico, Spanish Florida, Indian territory, the West, the Caribbean, and Europe.

Freedom seekers made their way into the south suburban regions of Chicago from various locations in an effort to escape bondage. According to McClellan, one known example involved the journey to freedom undertaken by Barney Ford.

Born into slavery in Virginia, Ford escaped captivity in 1848 and found assistance to travel overland to Chicago. While his exact route is unknown, he walked much of the way, passing Champaign and Kankakee on his route. He eventually married and played an active role in assisting other freedom seekers in the Chicago area.

“The stories of Illinois need to be included in the national story of the Underground Railroad and currently, they are not,” McClellan said.

McClellan, who said that he was increasingly drawn to the history of the region and particularly to places reflecting African-American settlement, wrote the book titled The Underground Railroad South of Chicago, which came out in 2019.

He has been researching the subject for over thirty years. “Along the way, I ran into references to the Underground Railroad and began to see that this has been a vital but almost forgotten part of our region’s history.”

McClellan found evidence to suggest that freedom seekers traveled through Crete, Lockport, New Lenox, Mokena, South Holland, Park Forest, and Sauk Trail. Situated twenty to forty miles outside of Chicago, these suburban locations were known as stopping off points or places of refuge for freedom seekers.

“There really is a lot to be proud of that this area was very much a part of the Underground Railroad story. Literally, hundreds of freedom seekers came right along the Sauk Trail,” he said. “Over the years, 3,000 to 4,500 freedom seekers came this way.”

While the nature of the Underground Railroad was a secret, current efforts are not, and there is an attempt to identify former Underground Railroad sites and garner national recognition for them in the south suburbs. Tom Shepherd—who is the lead organizer of the Little Calumet River Underground Railroad Project—McClellan, and other members of the group are spearheading it, but similar efforts date back to 1999.

In order to be recognized as an historic site in the National Park Service’s Network to Freedom registry, a site must be a location that has a demonstrated and verifiable association with the Underground Railroad, and applications are accepted twice a year in January and July.

Making a case for these sites and raising public awareness has been the focal point for the group. “We have three particular missions,” said Shepherd, “and one is to get some type of a memorial at the Ton Farm site or nearby.”

The former Jan and Aagje Ton Farm, which is listed in the national registry, sits on the Little Calumet directly south of the area generally referred to as Altgeld Gardens and the Golden Gate neighborhood. The Golden Gate neighborhood extends from 130th Street south to the Calumet River.

The actual site of the original home and outbuildings of the Ton Farm is now home to Chicago’s Finest Marina, a Black-owned motorboat marina located at 557 E. 134th Place in Chicago.

“We’re also looking at the Beaubien Woods and the forest preserve,” he said. The farm was located near the Beaubien Woods Forest Preserve and is said to have been one of the stops where freedom seekers could find shelter.

“Our number two mission is to establish what we call the ‘freedom trail,’ and the third is to get our curriculum into local schools,” Shepherd said.

The Crete Congregational Church and the I&M Canal Headquarters building in Lockport are listed on the national registry as well.

“A lot of the focus and energy right now is looking at the markers and the history signs that we’re trying to establish,” said McClellan. The group hopes to install the signs by the end of May at which time a celebration and, hopefully, a tour can take place.

The group received a $4,000 grant from the National Park Service and $1,800 from The Illinois State Historical Society to establish these markers. “What we really want to point to is the reality of freedom seekers coming through the region and the reality of Ton Farm and the Dutch settlers that responded,” McClellan stated.

One account of the role that the Ton Farm played in assisting freedom seekers recounts how the Tons worked closely with friend and fellow Dutch settler Cornelius Kuyper to assist three young runaway slaves. Kuyper hid the slaves in his home, then pretended to join the slave catchers in a futile attempt to re-capture them.

When the slave catchers retreated empty-handed, Kuyper called the men from their hiding place and packed them into the bottom of a large wagon, which he drove to the home of Jan Ton, wherein Mr. Ton ensured their safe passage to the next station. This system was repeated until the men reached Canada safely.

Stories such as these serve to underscore the important role played by those willing to assist those formerly enslaved. There were a significant number of African-American people directly involved with and providing leadership for the networks of the Underground Railroad, McClellan wrote in his book, and in the region south of Chicago there were Black residents scattered across the area helping freedom seekers.

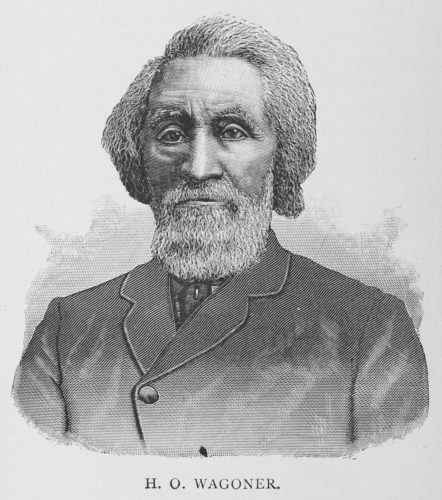

One noteworthy example was Henry O. Wagoner, a Black abolitionist and one of the key leaders of the efforts of the Underground Railroad in Chicago. According to historical accounts, Wagoner was also a typesetter and journalist who played an active role in the anti-slavery movement both through public writings and covert Underground Railroad activities. In 1843, he settled in Chatham, Ontario, which was a popular terminus for the Underground Railroad.

Anyone interested in learning more about the Little Calumet River Underground Railroad Project, the historic markers and/or upcoming events can follow the group through their Facebook page.

Dierdre Robinson is a writer and accounting manager in Chicago. She has a BA in Journalism from Michigan State University. She last wrote for the Weekly about the Annie B. Jones Civic Arts Center.

Love the knowledge

Thankyou for that history. I grew up in Englewood in Chicago. Loved going to the Chicago Historical Society on Clark st.St.. I taught and coached at Fenger and Tilden High Schools

I was raised in Altgeld Gardens 1956-1970 …’70 my Mom moved to London Town Houses…My father’s father John Elder Bigham was a Pulman Porter,there a article about him in the Defender ,I have to ck the date…My unk,Ted Smart was also a Porter…I will c if I can locate that article n send it to the Musem or to whom ?

Great to read the history! As a direct ancestor of Cornelius Kuyper it’s great to hear validation of our family’s legends.

I grew up in Altgel gardens on 134th street we used to sneak down to the little Calumet and fish. The area woods, River etc. was part of our play ground it was magical growing up out there in 50s and 60s I was so glad to find out about the rich history that area played in the survival of some of our ancestors.