Across the state, parents are sending their kids to public schools, visiting state parks, and living life as usual. But Illinois is facing a severe budget crisis that is anything but usual. Governor Bruce Rauner and the Illinois General Assembly allowed the state’s temporary income tax to expire at the beginning of the year, creating an enormous gap in the budget that has yet to be resolved. The governor refuses to negotiate on a budget until state Democrats agree to several of his proposed reforms, including restrictions to collective bargaining rights. The governor also wants a freeze to property taxes. “Property tax relief is one of our most pressing challenges,” he said in a February press conference. “Our property tax burden is one of the biggest impediments to growth, and it hurts both businesses and middle-class families.”

Although Rauner says he’s looking out for the middle class, House Speaker Michael Madigan and Democrats see his proposals as injurious to middle-class workers and families, and they have been uncooperative with the governor. Illinois has entered a fourth month of operating without a budget, and the effects of the crisis are felt acutely in many communities, the South and West Sides of Chicago key among them.

Kwame Raoul, Democratic State Senator from the 13th District, says that budget woes have disproportionally impacted the less fortunate. “We are actually funding a significant portion of the budget,” he says. “However, there are some areas that aren’t necessarily included in that, and that tends to be some of the social services that the everyday person doesn’t necessarily rely upon, but those with greater need rely upon.” This is reflected in an August report by Illinois Senate Democrats. According to the report, almost ninety percent of the state’s general funding is unaffected by the impasse due to court orders and other arrangements. But social services including youth programs, health initiatives, and care for children, seniors, and the disabled, are among the now underfunded portions of the budget.

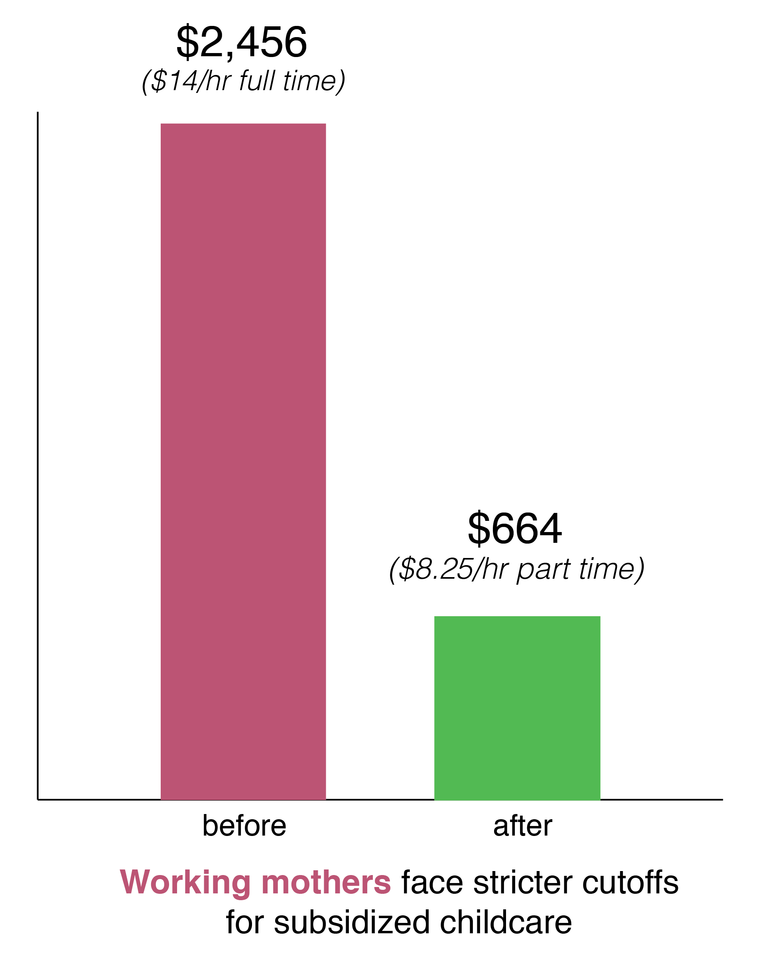

Democratic State Representative Christian Mitchell of the 26th District agrees with Raoul. “All the cuts are affecting the South Side a different way, just because you’ve got more low- and moderate-income people.” As an example, he mentioned that working mothers often rely on free childcare. With new eligibility rules in place, a working mother making over $664 a month no longer qualifies for childcare. In the past, single parents with one child could make over $2,400 and still qualify. As a result, Mitchell argues, “You’ve got entire ships of folks who can no longer go to work because they’ve got to take care of their kids.” Early in September, the Emanuel administration announced that it would set aside $9 million for Chicago children affected by the state’s cuts.

Senior care programs are also being threatened. According to a report from Voices for Illinois Children’s Fiscal Policy Center, there are serious threats to services including senior centers, transportation, and housing. Funding for the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), which serves 60,000 low-income families across the state by keeping their houses cool in the summer and warm in the winter, has been stopped, and families on the program endured the heat of the summer’s last days without assistance. The services provided by LIHEAP are provided only for those living at or below 150 percent of the federal poverty line, and since much of the South and West Sides have poverty rates between forty and sixty percent, the fluctuation in temperature poses serious health and safety risks to locals.

Mitchell questions the ability for people in his district to live “vibrant lives” when facing such severe restrictions on their time and health. “For folks on the South Side, the cuts to childcare, the cuts to senior care—these are all programs that working families rely on as basic economic supports to keep their jobs and to make sure that their kids and their parents are being well taken care of while they work to build a better future,” says Mitchell, his voice tinged with frustration.

Some critics have even attributed the eighteen percent increase in homicides this year as of June to the budget impasse. “It’s not like someone will grab a gun if they can’t get a summer job,” Raoul says, “but if the community is better economically stabilized, it will have less crime. There was no fruitful job program from the state, and the social services that would normally open their doors are on a shoestring budget.

“So you don’t have various groups competing for the attention of young people,” he continues. “You don’t have the positive groups, and the negative ones tend to win out.”

Without state-funded summer programs, youth were left without activities for months. Higher education programs have also been threatened. “If you’re a kid who’s done everything right in high school and is academically qualified to go to college,” Mitchell explains, “the state helps pay for it because better education is really good for the state. That program [the Monetary Award Program (MAP) Grant program] has been cut.”

Healthcare, care for children and the elderly, and student support services are not the only areas that have felt the brunt of the budget crisis. Like many social services in the state, Mujeres Latinas en Acción, a Pilsen-based agency providing critical services including aid to those affected by domestic violence in Chicago’s Latina community, is struggling desperately to continue as many of their programs as possible. Despite being forced to suffer the loss of twenty percent of their workforce, Mujeres is currently running their services without their expected allocation of $65,000.

As the state continues to operate without a budget, it is organizations like Mujeres—offering services such as childcare, youth programs, domestic violence support, and Latina empowerment programs—that are hurting. According to Adriana Viteri, Associate Director of Development and Public Affairs at Mujeres, the agency has been hit hard. Until funding resumes, their Latina Leadership program, a twenty-week program facilitating leadership and community involvement for women, will not be offered. There are no longer designated staff to provide public benefit case management and emergency economic assistance funds for survivors of gender violence. The agency has shut down their domestic violence police training, again due to a staff shortage, along with all of their community education efforts.

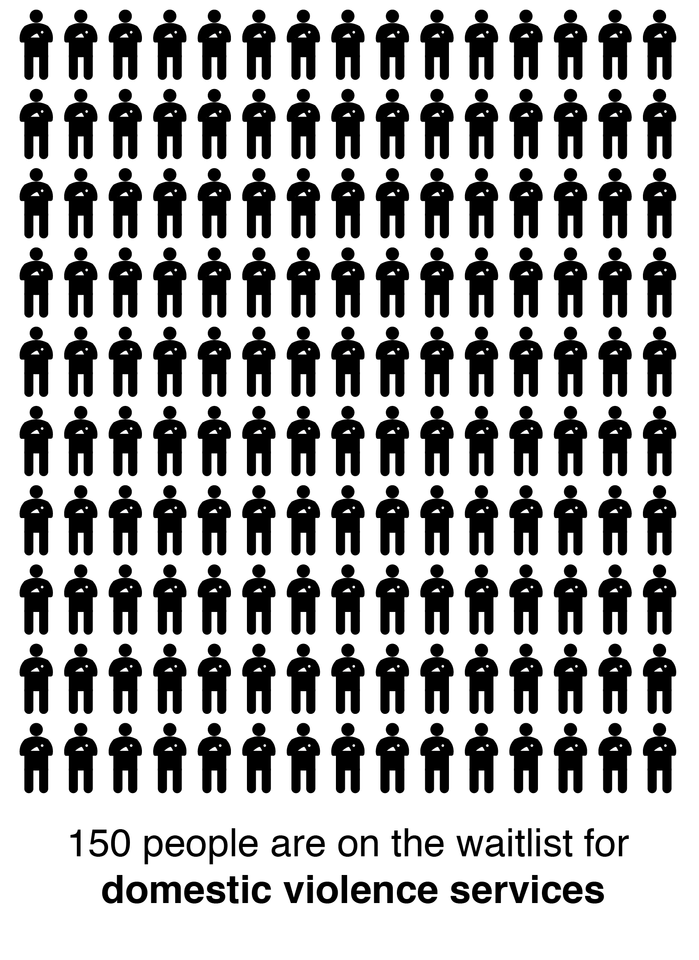

Even the programs within Mujeres that have managed to remain in operation feel the burden of the budget impasse. The lack of staff has increased the waitlist for domestic violence support service to 130 people, and Mujeres is not turning anyone away. Additionally, Viteri has noticed an increase in clients scheduling appointments but not showing up. This could stem from the scheduling delay, but there are other factors as well. “Mujeres used to help families who are very low income with transportation costs so that they could travel to make their appointments,” Viteri says. “We no longer have the funds to do this, and without bus fare, many clients are no longer able to come for services. This, coupled with the lack of childcare, makes transportation to our center an insurmountable hurdle for many of our clients.”

The disruption to childcare funding has affected other aspects of the agency’s services as well—participation in Mujeres’s afterschool youth programs has dropped, Viteri says, as older children are being asked to babysit for their younger siblings.

Another obstacle that has emerged is a rumor that Mujeres has closed their doors. “This is a dangerous rumor, as many individuals facing abuse may not want to leave their situation due to the fact that they believe they have nowhere else to get help,” Viteri says. Though Mujeres is referring all individuals to other organizations, Viteri says that the lack of culturally relevant services provided by other organizations as compared to Mujeres makes some of their clients reluctant to go.

Finding a solution to the state’s budget woes won’t be easy. Raoul and Mitchell are both adamant that the only way to resolve the budget crisis is for Governor Rauner and the rest of the legislature to come to a reasonable agreement. “Until that happens, we will not see a solution to this problem,” Mitchell says.

The price of the budget crisis is far greater than a temporary shutdown of social services. Even if the impasse is resolved and funding is resumed, at least in part, many agencies will not fully recover. “The sad part of the story,” Raoul explains, “is the extent of the social service agencies who will have to close their doors or lay off people. It’s not easy for a lot of those agencies to flip the switch and change directions. In most cases there is no reopening. If you lose your top people, you’ve really been decimated.”

“These aren’t rich people who are just volunteering their time, they’re working people who are devoting their lives to helping other families like them,” Mitchell says. “They can’t just wait it out and go back to their job.”

Mujeres Latinas en Acción has plans to overcome the loss of funding in the short term, but if the state crisis continues, it expects to terminate five to ten additional staff members and keep all remaining staff furloughed three days a week—a best-case scenario. In the worst case, Mujeres will have to shut down until payments for services rendered in the past three months are received. If the state cannot provide these funds, Mujeres may not reopen.

Like many legislators in districts that are suffering the most, Mitchell is eager for the crisis to be resolved. “I am ready and willing to work with the governor,” he says, “but until that moment happens, this will continue to have a deep and abiding and disproportionate impact on the South Side.”

Social service programs operating on shoestring budgets, state legislators fighting to protect their districts, and state advocacy groups are all clamoring for a resolution that remains a long way away. For the people of Chicago’s South Side, the situation will remain dire until that resolution comes. For them, the budget impasse isn’t just a political stalemate. Their health, their money, and their lives are on the line.

The actions ofthe Governorks office are reprehensible. Proud of the leadership that refuses to capitulate. Illinois cannot become a right to work state. To continue to tie his personal agenda to approving a budget is insensitive to the plight of babies, seniors, & community services……