Pam is standing in front of a rusted metal wall, unafraid and expressionless. She faces the camera of Todd Diederich, who tells me they’ve lost touch as of late, but that he still worries about her whereabouts.

“She matches the wall, she’s wearing her bleached shirts, the rust, it’s just like, that’s her environment. This is her world,” Diederich says. This is how she appears in Luminous Flux, a book of photographs he released last year. “I wish that’s the only picture I ever took of her, ‘cause that’s really how I see her,” he says.

Diederich depicts scenes of life, most frequently black life: funerals and homes, fights and tattoos, and—most famously—African-American queer balls. These are private moments and spaces laid bare for public viewing. How were these images made, and how does Diederich imagine they’ll be seen?

The portrait of Pam in Luminous Flux isn’t his only image of her. In an August 2011 installment of his now-defunct Vice series, “Todd’s People,” she’s “Pam With the Knife,” a hardened curiosity whose life has been irreparably marred by violence, drugs, and misfortune. Accompanying the series of Diederich’s portraits is an interview between the two.

What’s your name?

Pam.

I’m Todd.

What’s up man?

Nothing. Hey, you wanna put that knife down?

Why, you scared? And no.

She’s farther away from the camera there, confrontational, holding up a knife between her body and Diederich’s camera. And yet she’s behind a fence, encaging her in a way that feels safer for the viewer.

These Vice photos recall the work of Diane Arbus, a photographer famous for images of social outcasts in the mid-twentieth-century U.S. Decades of viewers have questioned Arbus’s relation to her subjects—whether she shared any connection with those she photographed, or whether she saw them as freaks to exhibit to the world. The people and the fashion in Diederich’s photos are also not unlike an American Apparel ad: exposed skin, neon short-shorts, faces bare or vividly made-up, and a distinctly pesky whipper-snapper cool that draws on the aesthetics of decades past. Many of Diederich’s photographs have captioned locations or include visible street signs, setting them in Chicago’s South and West Sides or in Los Angeles’s Compton.

Last year Diederich published Luminous Flux with the help of Matt Austin, head of Pilsen-based organization The Perch, which acts as a nonprofit, limited-edition publisher alongside other supportive roles for local artists. After a successful Kickstarter fundraising campaign, Luminous Flux sold its full edition of eighty-one copies in presale. The Perch is dedicated to publishing in the service of artists, and takes no money from sales. Austin is a personal fan of Diederich’s work, and invited him to collaborate on the book project in late 2012.

I ask Austin how he thinks Diederich manages to gain access to the communities and scenes he photographs. He chalks it up, enigmatically, to Diederich’s personality and openness about himself. “He’s asking us to look at things the way he looks at them,” he tells me.

This begins to make sense to me when I arrive at Diederich’s second-floor Pilsen apartment. Bounding up the unsalted, icy steps to meet me at the gate, Diederich explains that he’s been “partying, cleaning,” despite having gotten home at four that morning from photographing a queer ball in South Shore. He clears pairs and pairs of basketball shoes, including one with “DIEDERICH” stitched on the side, out of the way so I can sit down. The house is toasty thanks to an old-fashioned boiler in the front room, but, as Diederich points out, his apartment lacks both a stove and fridge. The Pink Line rumbles by every few minutes behind the building as we sit in front of his computer, Diederich frequently pulling up photographs as we speak.

He’s bubbly and engaging, informal in a way that feels welcoming. He ushers me into his world of photographs, not hiding works in progress or shots that aren’t his favorites. As Diederich sees it, his ability to connect with people results from the open structure of his life. “Life interacts with me a lot,” he says. “People just stop me in the street.”

His photographic output from a recent trip to Los Angeles includes a series of a male model friend, flaunting and posing at 2am in a wooded area, and photographs of boxers Diederich approached during their workout in a storefront gym. These are scenarios he walked into or created. He tells me it’s just a matter of pinballing through the world in the right way.

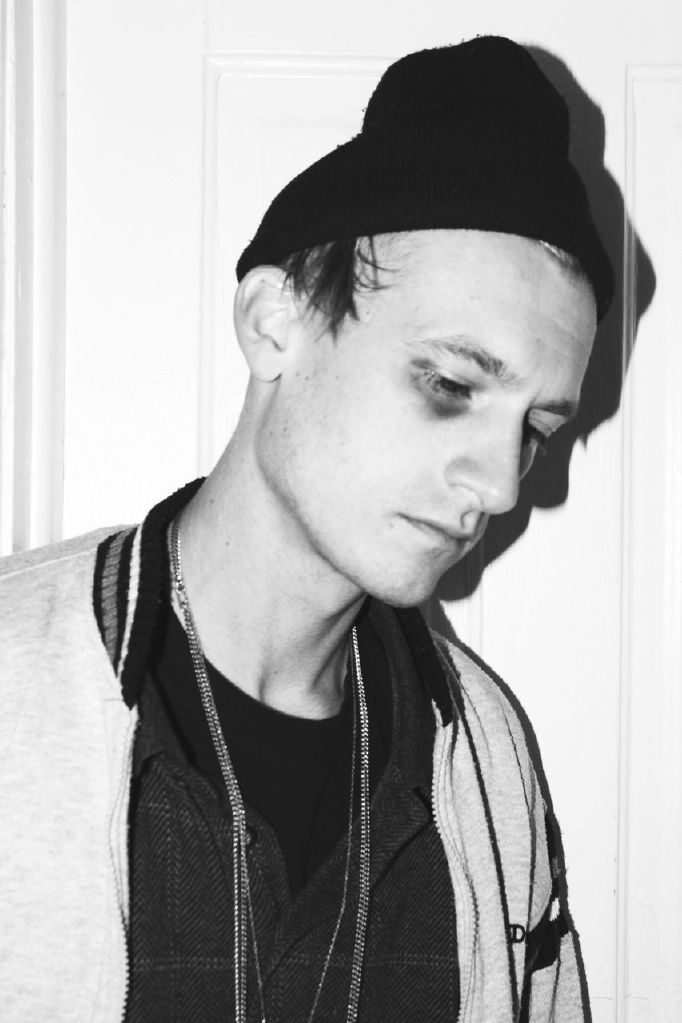

Diederich has a simultaneous visibility—his sense of style catches eyes and prompts questions—and a lack of widespread fame, a combination that often works to his advantage. His head is shaved, apart from a tuft of brightly dyed hair. He is tall and thin. When we meet he is dressed sleekly in black, set off, naturally, by a pair of basketball shoes.

“I don’t usually explain to them what I do,” he says of his subjects. “I just tell them the light looks really nice on them. Like, ‘Let me take a picture of you, homie, the light looks really good right now.’ As long as you compliment them, you’re in—usually.”

In part, Diederich sees his success in finding subjects as the reward of a calculated effort. “I literally will just lay down and try to visualize the kind of images I want,” he says. He considers himself unique in his way of moving through the world and capturing it. Diederich finds most art lacking in the quality that comes when an artist is “willing to die for it.” When pressed, he cites Larry Clark’s 1971 “Tulsa” series as an example of what can happen when artists do fully immerse themselves: “He probably couldn’t have got those pictures if he didn’t do drugs with them.”

Internal inconsistencies start to appear when our conversation moves beyond the theoretical to talk about his photography on the South and West Sides of Chicago. One recurring focus of Diederich’s work is the queer balls in these parts of the city. It’s a subculture he became aware of by searching the Web, a scene closely guarded due to both its unlicensed use of spaces and the marginalized identities of its participants.

Diederich, who has also attended balls in New York and LA, considers Chicago’s balls the least self-conscious, free from excessive concern about image and status. In Chicago, ball culture is linked back to the turn-of-the-century First Ward Balls, which notorious aldermen “Bathhouse” John Coughlin and Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna hosted for residents of the city’s vice district. Contemporary balls also draw from the traditions of drag balls, which were kept under wraps in an era when both black and queer cultures lacked spaces in which to gather openly. In Chicago today, queer balls are typically held late at night in warehouses or other out-of-the-way spaces.

After several years photographing balls and getting to know the scene’s mainstays, Diederich tells me, he’s gained a sort of ambassadorial status. He’s often the only white person present, and usually the only trusted photographer. The night before we spoke, he was welcomed further into the fold with an offer to join Infiniti House, one of the tightknit subgroups of Chicago’s ball scene. “They were like, ‘This is your welcoming ball.’ I’m Todd Infiniti,” he says.

Despite this, it’s still with something of an anthropologist’s distance that Diederich looks at balls and their participants. He remembers his first time seeing a ball, in a YouTube video. “Still to this day, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a group of people as authentic, as pure,” he says.

A complete look at Diederich as a producer has to be based in the difference between the way he sees his artistic practice and the ways it might appear to the rest of the world. In his photographs, mainly of African-American residents in Chicago’s poorest neighborhoods, many portrayed in situations of marginalization or hardship, an ambiguity arises that’s hard to shake. Is the viewer—perhaps a reader of Vice or the Chicago Reader, far removed from the situations and places shown—being shown power and confidence, or weakness and vulnerability?

“Photographing on the South Side, I feel like people would want to see more grit from me, and more grime, but I feel like I’m just trying to find power,” Diederich says. “And maybe your first time rollin’ around the hood trying to take pictures, maybe all you do see is the grime, you know, but you realize, like, kids live here. Children play here.”

Diederich’s photos might invite the viewer to see power, but in the way they publicize other people’s pain and hardship, they run the risk of perpetuating racist stereotypes and appealing to the same curiosities as a photographic genre like “ruin porn,” which features photographs of urban spaces in decay. It’s that risk, and the very idea of extracting images from “the hood” for display in galleries or online, that is left unexamined in Diederich’s search for the power in his subjects, even as he looks past what some see only as grit and grime.

“To me it’s rude, people thinking that people in front of my lens need help and I’m okay. I’m totally not okay,” he says. “Everyone needs help, everyone’s life could be better.” Diederich feels, or wants to feel, that his intentions are enough, but if you consider a viewing public that might lack access to that information, that defense falls flat. In the end, there are certain dynamics and histories—of identity, and of Chicago’s pervasive racial segregation—that can’t simply be willed away in the processes of making or showing images.

It’s like Pam’s story. I read “Pam With the Knife” on Vice and learned of her as one of “Todd’s People.” In the short interview he talks to her about her illness, her suicide attempt, her cynicism—the distance between her life and Diederich’s seems absolute. I talk with Diederich and I learned of the time they spent together, of her warmth and strength. But not everyone gets to talk with Diederich.

What a great interview and the photos and stories that Todd has made.shows he is a true artist, I am proud. His mother, Susan Diederich.