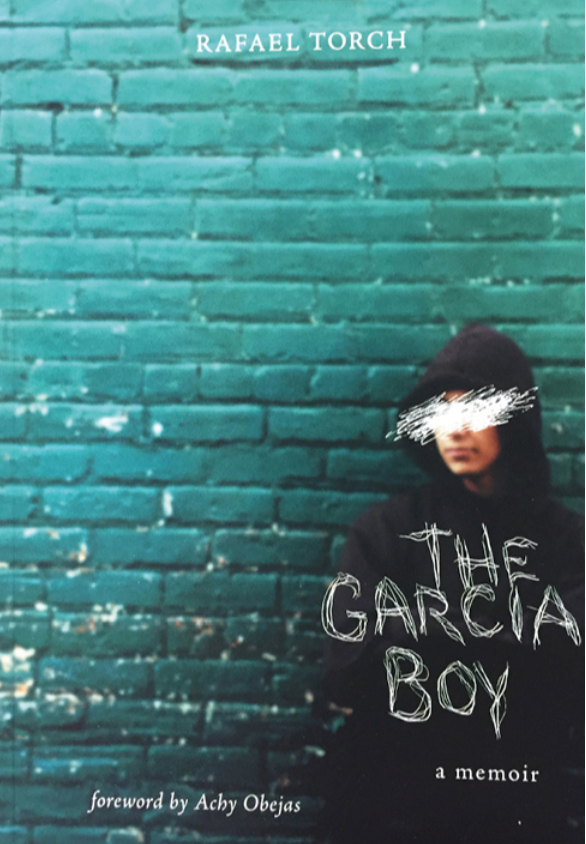

Despite dying nearly a decade earlier, Rafael Torch made a dramatic splash at this year’s Printer’s Row Lit Fest, shining with his lapidary prose in a book he wrote fifteen years ago. Released earlier this year, The Garcia Boy was put together with the help of Torch’s widow, Emily Olson-Torch, and students in DePaul University’s creative writing program and published by Big Shoulder Books, DePaul’s press that “disseminate[s], free of charge, quality works of writing by and about Chicagoans whose voices might not otherwise be shared.”

Big Shoulders’s founding editor is Miles Harvey, an associate professor of English at DePaul, who discovered Torch when a literary journal editor insisted he read the essay “La Villita,” which ended up becoming the first chapter of the book. Harvey reached out to Olson-Torch, who eventually furnished the unpublished manuscript and a host of supplementary materials that Harvey’s class shaped and edited into a finished book over the course of the class, molding the clay of 400-page, 350-page and 200-page drafts into a final, finished product last year.

At the Lit Fest, which took place June 8 and 9 in the Printer’s Row neighborhood in the South Loop, and which is the largest literary festival in the Midwest, the university press handed out free copies of Torch’s book to anyone who stopped by its tent, and has distributed them across the country. On June 8, Olson-Torch and the book’s editors had a panel discussion at the Grace Place Church in Printer’s Row about “the best Chicago writer whose name you don’t know,” attaining long-overdue recognition on WGN Radio and other media outlets.

Torch’s autobiography deserves as wide an audience as possible. It is candid and unflinching, brave and poignant in its descriptions of alcohol and drug abuse, of street gangs and violence, and of the descendants of immigrants searching for a sense of identity and belonging, seeking to reconcile the time-honored heritage of their past with the boundless possibility of their future.

The Garcia Boy is a powerful memoir, but it’s not Torch’s story alone. The late writer, who died in 2011 of sarcoma, a rare form of cancer, at the age of thirty-six, largely tells the story of three people: himself, an alcoholic who overcomes his addiction to become a husband, acclaimed essayist, high school teacher at the Latin School and dean at the largely Latinx Cristo Rey Jesuit High School in Pilsen; his father, an undocumented immigrant from Mexico and combative drunk he spars with; and a student at his Catholic high school named Sergio Garcia whose life was tragically cut short because of gang violence.

Sergio Garcia’s death haunted Torch because it just as easily could have been him: “a dead Mexican in the beaten-up back seat of a cheap car bought with someone else’s savings.” The grisly murder in a dark street of a teen who was fraternizing with gang members forced Torch to see his environment in a new light. His death is written with a stark, knowing realism—the Garcia boy wet his pants after dying, and was shot in both the chest and head as “a billboard, a plain message to someone in some other hood or gang.”

Torch felt a strong sense of identification with the boy from a similar background: “He is me and I am him.” His heartbreak is raw, such as when he’s forced to repeatedly skip over Garcia’s name while grading papers for the rest of the school year: “His name and a history of missing assignments, tardies and absences. Then there is nothing.” It’s a story shared by many across the city and a powerful depiction of the human toll of the violence that claimed several hundred lives a year across Chicago in the early 2010s.

An account of growing up as an American of Italian and Mexican descent in suburban Cleveland and Chicago during the late 1990s and early 2000s, and teaching in the city in the early 2000s, the book covers a lot of ground despite clocking in at just 156 pages. Torch explores addiction, street gangs, and how the children of immigrants integrate into America, asking what it really means to be American. He probes the conundrum faced by some second-generation hyphenated Americans who feel perpetually betwixt and between.

Torch viewed his identity as complicated, describing feeling like a foreigner while on a trip to Mexico and like a stranger in the immigrant neighborhood where he grew up. The alienation is thick as he drives through Pilsen: “The wasted, neon lights of 18th Street flash by the windshield. Slick, wasted boys at the street corner, angels in their regalia. Their eyes meet mine, and after a brief second there’s something like recognition and then again I’m just passing through, a tourist, a güero. A white boy. I creep through the full simulacra of my immigrant Chicago. It sits heavy and ready to pop as a warm summer breeze comes out of nowhere and makes me want to roll down the window for a moment and take it all in again for the first time, innocent and less cynical about the future.” He’s keenly aware of the duality of identity, riffing on flipping between Spanish- and English-language radio stations or a playground he views as “the green light Fitzgerald mused about” and a symbol of America that he notes is across the street from a bar with a neon sign that says “Cerveza Fria.”

Torch’s writing has a lilt and a precision of language that brings it to life. His literary talent is on full display with firecracker prose like “my father fled the bullets and mayhem in a country lost in the wild winds of a dust storm, the ghosts of Pancho Villa nobody cares about anymore, the Emiliano Zapata who failed his people, the Mexico City earthquake and the nightmare hangovers from drinking bathtub tequila of mezcal.” A specter of unrealized potential hangs over the work, a hazy penumbra of what could have been.

Before his abrupt death, Torch earned a master’s degree in Humanities at the University of Chicago and became a dean at the private high school where he taught English. He published in journals like Indiana Review, Antioch Review, and Crab Orchard Review. His published literary output during his lifetime was limited to a smattering of essays, but his memoir shows a major talent. (After his death, a literary award was established in his honor.)

His prose reaches great heights of lyricism: “The Garcia boy is an urban myth now, one of those sad stories to add to the repertoire of sad American communities at the edge of the twenty-first century. I see long cold cinematic shots of the dangerous remnants of buildings and broken glass and hungry murderers and hunted prey that resemble people. The Garcia boy and the music give me images of empty, half-torn-down buildings like the ones that line Roosevelt Road near Blue Island Avenue and those on North Halsted near Division, near busted, rotted-out, rusted steel bridges creaking in the ferocious summer wind sweeping up all the dust and skimming it across the top of the Chicago River. Reality sets in, and the wrecking ball waits for no one.”

The Garcia Boy paints vivid pictures of the city, such as slack-jawed gaping at the city’s sheer rust-kissed majesty and the “dark blue abyss of Lake Michigan” while driving over the Chicago Skyway for the first time or drinking at a downtown bar while a secretary moonlighting as a bartender keeps the beers coming. Committed to capturing the spirit of the place, he memorably describes Pilsen as a “densely populated area, awash with newcomers and old-timers, well-oiled Americans still clinging, like it or not, to their Mexican identity” as a neighborhood that “has changed the Mexicans–who believe so much in the Past–into people of the future.”

Despite student editors’ efforts to reassemble it, the book does suffer some structural issues. It can read like a hodgepodge of shorter essays that were glommed together haphazardly. There are time jumps, discordant themes and the abrupt, awkward introduction of his first struggle with cancer in the epilogue. The chronology bounces all around. But despite minor flaws in organization, it stands as a powerful voice of witness and testimony to widely shared experiences. Through his memoir, Torch also transformed parts of the past into something we can take with us into the future.

Rafael Torch, The Garcia Boy: A Memoir. Free upon request. Big Shoulders Press. 156 pages.

A regular Weekly contributor, Joseph S. Pete is a Lisagor Award-winning writer whose work has appeared in more than 200 literary journals and a few zines. His one-act play Thank You For Your Service will be staged at the Veterans 10-Minute Play Festival at Salem State University in Massachusetts this September, and his book Lost Hammond, Indiana is coming out later this year.