In the first few seconds of a video that ridesharing company Uber posted to YouTube on October 19, a man walks to the curb outside an apartment building, puts down his suitcase, and looks around at the empty street, without a car in sight to welcome him. The scene shifts to another Chicago street, where an African-American woman waves and waves at a taxi that sweeps right by her.

A solemn voiceover accompanies the video: “You never know. Will a taxi show up in your neighborhood? Will an empty cab pass you by? That’s the reality with taxis. But now you have a choice. With just a touch of a button, Uber will show up anywhere you are. South Side, West Side, anywhere.” The ad goes on to implore viewers to call their aldermen and support Uber’s bid for the right to pick up passengers at Chicago’s airports (Uber ultimately got its will, as the city started allowing ridesharing companies to pick up passengers from the airport in late October).

This thirty-second advertisement exemplifies one of Uber’s current strategies to gain support in Chicago: demonstrate its commitment to the often underserved South and West Sides. As competition between ridesharing services like Uber and Lyft and traditional taxis plays out here and in cities across America, Uber Chicago has used this rhetoric to claim superiority over taxi companies. Taxi drivers, for their part, accuse Uber (especially UberX, the service which allows drivers to use their own cars) of providing the same services without adhering to the same regulations and inspection requirements.

As part of its effort to win over Chicago consumers, Uber has broadcasted statistics about its friendliness to the South Side. Fifty-four percent of Uber’s Chicago rides begin or end in “areas deemed by the city as underserved by taxi and public transportation,” according to Uber Chicago spokesperson Brooke Anderson, who added that it takes an average of five minutes to request an Uber on the South and West sides.

Uber has also heavily recruited new drivers in these areas. In June, the company announced an initiative to recruit 10,000 new drivers from the South and West Sides—by October 23, they were halfway to their goal. In September, they joined Pastor Michael Pfleger of St. Sabina Church in Auburn Gresham to announce Xchange, a car leasing program that helps potential Uber drivers lease cars at affordable rates. Uber has also held job fairs throughout the South Side and continues to plan more.

“We connect drivers with the closest ride, and that ride takes them to their next area,” Anderson said in an email. “Ridership on Chicago’s South and West Sides is growing, and our effort to recruit more drivers there will help ensure that people who live in the community are benefitting from that growth.”

Uber’s focus on the South Side is significant in this oft-neglected region, and the company’s interest in providing jobs and rides south of Roosevelt is attracting enthusiastic riders and drivers. Still, controversy remains—taxi drivers maintain there are other ways to increase service to the South Side, and not everyone agrees that Uber is an ideal employment opportunity for South Siders. Furthermore, discontent simmers among Uber drivers who claim the company’s model makes it hard to earn what they had expected.

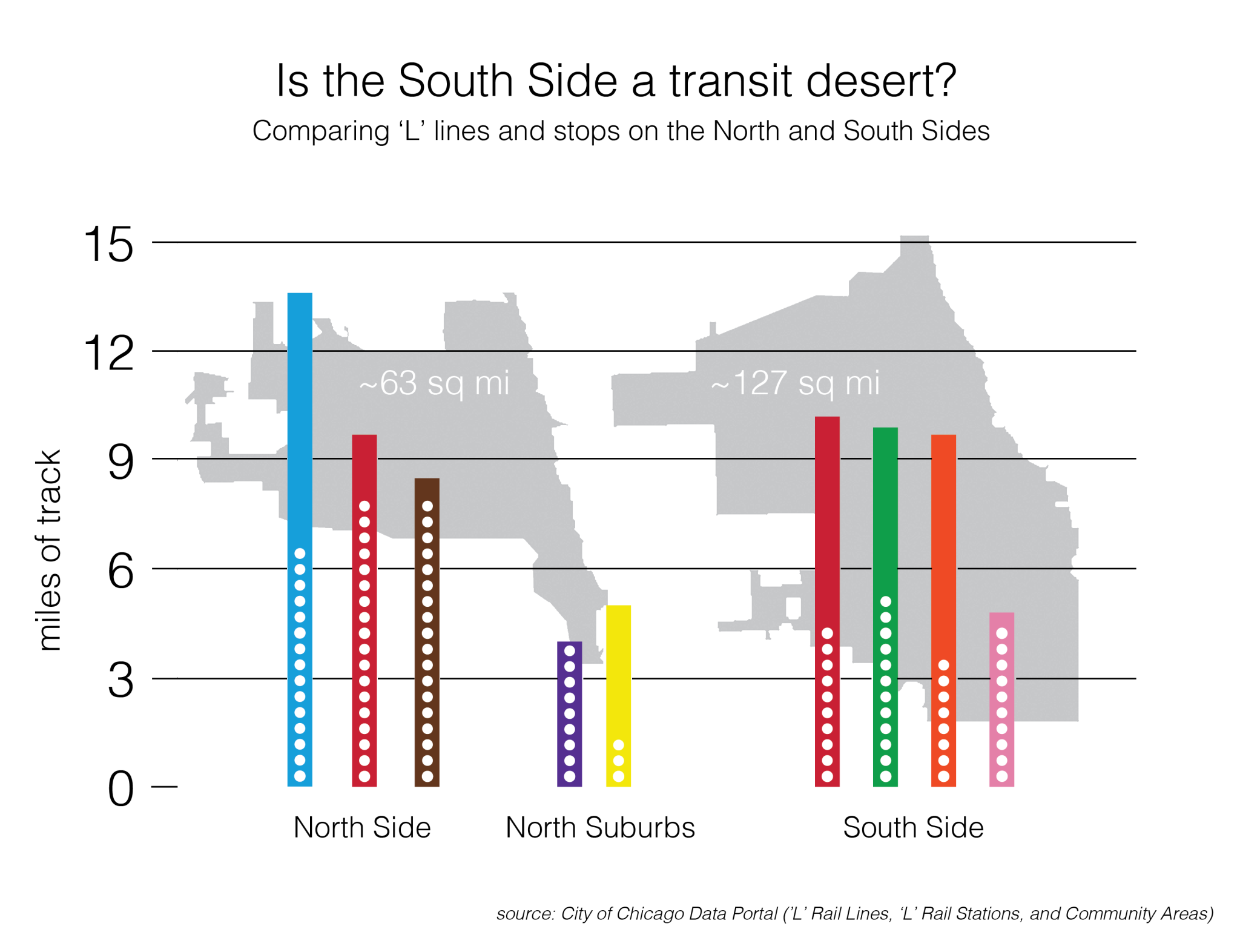

Understanding the South Side’s role in the battle waged between Uber and taxis requires the context of South Side transportation history. The South Side has long been underserved by both public and private transportation: any map of the CTA makes it evident that North Siders have a larger selection of ‘L’ stops.

Todd Schuble, a geographic information systems specialist and social sciences lecturer at the University of Chicago, attributes Chicago’s current transit infrastructure to the city’s historical development. Originally, Schuble says, most of Chicago’s rail yards were on the South Side, an obstacle to the construction of public transit. The abundance of industry on the South Side meant that workers often lived nearby and walked to work.

“There’s a huge disparity with regards to population density,” he said, in that people live much closer together on the North Side than they do on the South Side.

Schuble called the city transportation strategy “reactive,” meaning it responds to population demand, rather than “proactive,” which would mean creating transportation options (such as more light rail transit) that would increase the population and improve opportunity.

“That’s the transportation infrastructure across the United States, sadly,” he said. “Some urban areas are investing in the future and some can afford to, some can’t. Chicago’s one of those that really can’t, unfortunately.”

Uber presents itself as one solution to these problems. In the second part of Anderson’s statement, she writes, “Transportation equity is something we are very passionate about…Improving access to transportation in areas that need it is good for riders who now have the power to push a button and get a ride, and drivers who benefit from the increased economic opportunity of providing that ride.”

Of course, it’s hard to consider Uber a stand-in for public transit due to the disparity in cost. Schuble pointed out that regularly taking Ubers may be beyond the disposable income of many South Siders.

A more apt comparison would be to consider ridesharing services like Uber alongside taxis, which have long been accused of discrimination in U.S. cities. In July, Sun-Times columnist Laura Washington published a piece called “Uber upends problem of ‘hailing while black.’” After describing her own history of being “dissed, ignored, waylaid, and mistreated” when attempting to get a taxi, she quoted a study conducted by pollster Cornell Belcher, which showed that sixty-six percent of African Americans thought taxi cabs deliberately avoided picking them up. Complicating matters is the fact that the study was commissioned by Uber—another indication of the company’s eagerness to capitalize on an already-present distrust of taxis.

While the study may be another part of Uber’s marketing plan, it clearly has resonated with those like Washington who have been frustrated with taxi service. On September 9, the day before he hosted an Uber hiring event, Pfleger wrote a Facebook post criticizing a lack of taxi service at St. Sabina. “NONE of the Cab companies respond when we call for a cab to come to St. Sabina,” he wrote. “Uber does!!! And the Cab companies have never asked to have a Hiring event on 78thPl. and Racine.”

In June 2014, Emily Badger of the Washington Post examined complaints about taxis made to Chicago’s Business Affairs and Consumer Protection agency and found a host of complaints of racial discrimination, discrimination against those with disabilities, and refusals to go to the South Side.

But while the two taxi drivers the Weekly spoke to admitted that neglect of the South Side is a problem and that racism and fear of the South Side exist among taxi drivers, both attributed the lack of service to the South Side mainly to economic concerns.

Peter Ali Enger, a cab driver and the secretary of the United Taxidrivers Community Council, which supports certain “grassroots taxi driver-led struggles,” agreed that some taxi drivers are afraid, because “when crimes happen, the general sense is that there’s some neighborhood where more crimes happen.” However, he added, “that’s not the main component, the main component is economics.” While he doesn’t agree with this practice personally, he said that since there are often fewer fares on the South Side, many drivers are reluctant to spend gas money taking passengers far into the South Side should they not find passengers on the way back.

“That’s not a good reason, that’s not an appropriate reason,” said Enger. “We should take people wherever they want to go and eat that risk.”

Cheryl Miller, a cab driver from the Kenwood/Oakland area whom the Weekly found through the union Cab Drivers United, said that she spends part of her day on the South and West Sides, but that there aren’t as many taxi drivers there. However, she also said the state of the economy in recent years had made earning money in the areas more difficult.

“Whenever there’s an economic downturn, it’s going to hit the South and West Sides harder and longer,” she said. With this in mind, she has started spending more time working downtown.

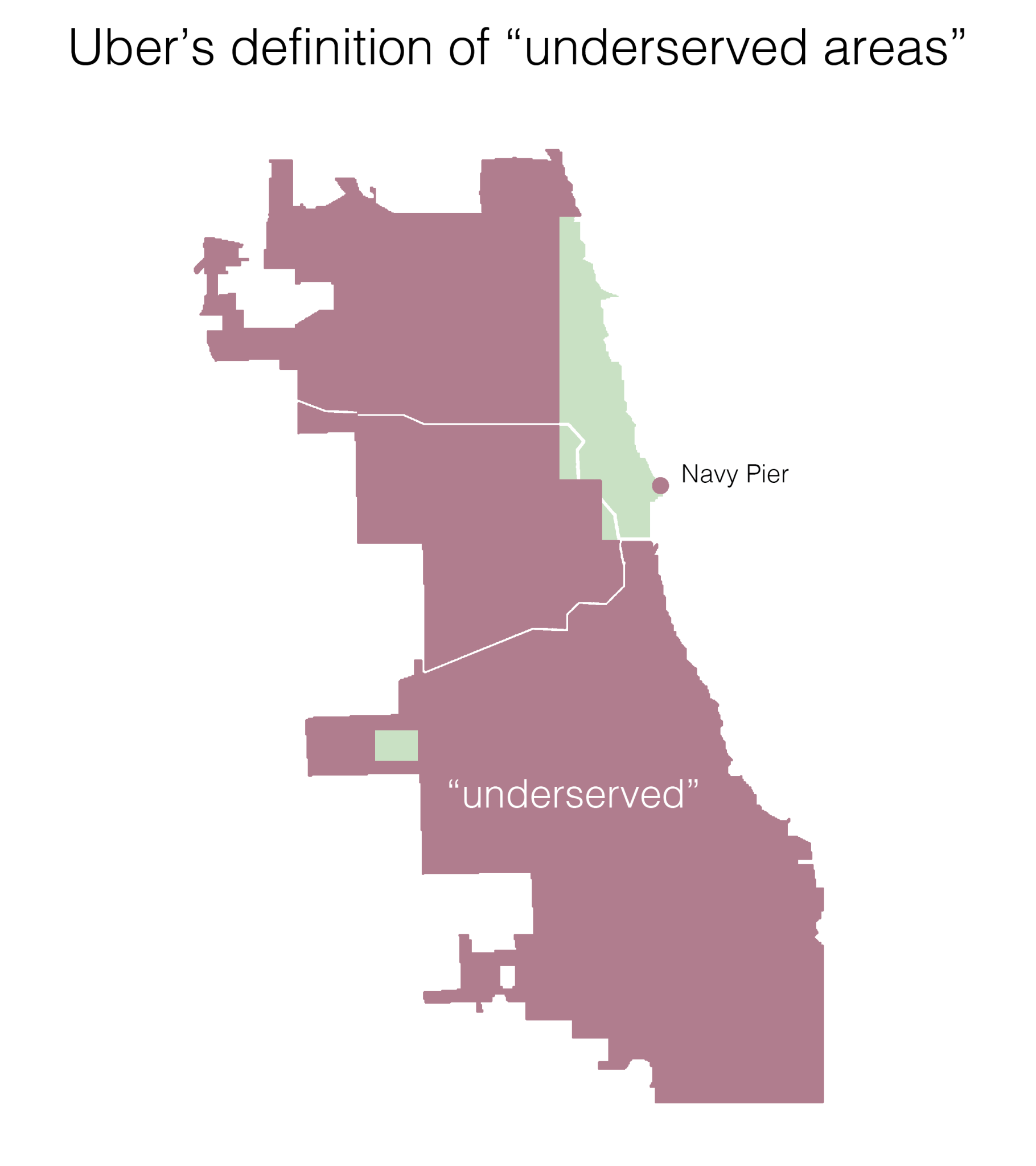

But not all of this behavior is unique to taxis. Uber’s impressive statistic—that the fifty-four percent of rides start and end in underserved areas—is somewhat misleading: the definition Uber uses for “underserved areas” is not restricted to the South and West Sides. Anderson cited a city document last updated in 2012 as the source of Uber’s definition, under which the boundaries for underserved areas include north of Devon Avenue, west of Ashland between Devon and Grand, west of Halsted between Grand and Roosevelt, and south of Roosevelt, with the exclusion of the airports (and, for some reason, the inclusion of McCormick Place on Sundays). The enclosed area includes places like Wicker Park and Logan Square, the very neighborhoods that Chicagoans probably associate with bar-hopping millennials and Ubers swarming around to collect them. (It is unclear whether the city still uses this definition.)

This casts a new light on Uber’s assertions, but perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising; Uber drivers also have to make ends meet. As Enger pointed out, the same economic disincentives that may keep taxis out of the South Side could have the same effect on Uber. He was skeptical that adding more South and West Side drivers would necessarily lead to more rides in those areas, since the drivers might leave for the North Side to get more fares.

“When I start on the South Side of the city, more times than not I wind up on the North Side of Chicago,” said one Uber driver who requested anonymity to keep his job with Uber safe. The driver also works for Lyft.

But he also said that the expansion of South Side drivers could improve the availability of South Side rides: “Maybe you will have local people do local trips now and they’ll go ahead and do the fares within their own neighborhood, instead of someone having to come further and get them.”

Gersh Mayer, who has been driving for Uber for five months but has driven for various services, including a cab company, since 1961, said that from his experience, Uber drivers are sometimes guilty of discrimination as well. Mayer, who’s from Hyde Park, sometimes posts on a forum called UberPeople.net, where Uber drivers congregate to discuss their work, and spoke of threads where drivers discuss which neighborhoods in Chicago to avoid. The Weekly found drivers posting about this topic on the forum as well.

“There’s no question that a lot of people are getting service that weren’t getting it before,” Mayer said of Uber’s ridesharing services, but at the same time, “most folks driving UberX are not bopping over to Englewood or Pullman or Roseland to get a cup of coffee.”

Schuble said the breakdown of stigma over the South Side is essential for improving transportation in the area.

“It’s like, people live there, okay?” he said. “It’s not like it’s some zone where it’s completely uninhabitable and it’s just sort of reckless, it’s not like that at all.”

While Uber may posit itself as part of that improvement, taxi drivers and supporters maintain that there are other ways to increase service to the South Side. Having already purchased or leased the expensive taxi medallions that are required to drive a cab, taxi drivers are concerned about making up those expenses and are fearful that ridesharing services will eventually siphon off all of their business.

In early October, Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced a tax credit program for both taxis and ridesharing services that would incentivize picking up passengers in underserved areas. Enger, however, is skeptical that this will have any impact, given the difficulty for the driver of keeping track of all the records.

Enger’s solution is an idea he pitched to the city for a universal taxi dispatch app, which would allow passengers to electronically summon a taxi, just as they would an Uber. The city put out a request for proposals for the app in May, and Enger said it will be released in the upcoming months. (At press time, the city had not responded to requests for confirmation.) He thinks the convenience of electronic payment, as well as the fact that users will be able to access all the taxis in the city rather than just from one taxi company, will be popular among consumers.

Enger’s solution is an idea he pitched to the city for a universal taxi dispatch app, which would allow passengers to electronically summon a taxi, just as they would an Uber. The city put out a request for proposals for the app in May, and Enger said it will be released in the upcoming months. (At press time, the city had not responded to requests for confirmation.) He thinks the convenience of electronic payment, as well as the fact that users will be able to access all the taxis in the city rather than just from one taxi company, will be popular among consumers.

“The more reliable we become, the more likely it is that people call us,” said Enger. “People on the South Side have fallen out of the business of calling taxis because they can’t get one.”

Enger also said a guaranteed electronic payment through the dispatching app could help assuage cab drivers’ fears of not getting paid or of having wads of cash stolen, which could make them less nervous about entering areas they consider dangerous.

In response to the prospect of a taxi dispatch app, Anderson of Uber wrote, “We welcome competition.”

When questioned on whether the taxi app would really be able to compete with Uber’s lower fares (excluding its times of surge pricing), Enger said that some people would pay a few extra dollars for the safety he believes comes with the increased regulation of cabs or just for ethical reasons.

Another alternative, cab driver Cheryl Miller suggested, is a revival of the city’s underserved medallion program, in which the city gave some drivers a medallion for free if they did a certain amount of service in underserved areas.

“By reducing the cost to drivers, it made it feasible for drivers who wanted to work in the neighborhoods to actually be able to do so,” she said. However, “when medallion prices started to climb, it was more profitable for the city to sell them at an auction.”

Both Miller and Enger see preserving taxi careers against the encroachment of ridesharing companies as a way of maintaining full-time jobs that have historically opened a path into the middle class. They contrast this with Uber’s employment model, in which many drivers work part-time.

Uber, however, actively promotes the fact that drivers can work part-time and have flexible hours. Anderson wrote that more than fifty percent of drivers use the Uber platform less than ten hours a week. Andrew Wells, director of the Workforce Development Center at the Chicago Urban League, said that the Urban League partners with Uber so it can refer those who come in looking for more flexible work.

“If they don’t want to be bogged down from nine to five, then Uber was the best choice for them,” said Wells. “And many of them love the money they’re able to make. They’re able to pay their bills.”

However, while Wells said the drivers he had referred to Uber were satisfied and Pfleger wrote in an email that the drivers he had spoken to liked it, others are not so optimistic about Uber’s opportunities. Discontent plays out publicly on the UberPeople.net forum, and Mayer and the anonymous Uber and Lyft driver articulated some concerns to the Weekly. Just as taxi drivers worry about making ends meet, some Uber drivers struggle with the same challenge under the company’s employment structure, both here and beyond Chicago. In October, some Detroit Uber drivers went on a weekend strike to protest the company’s lower fares.

One factor in their discontent is the commission that Uber takes for each ride, which has been rising, according to drivers. The anonymous Uber and Lyft driver said that Uber’s commission was ten percent when he first started, but it rose to fifteen and then twenty percent. He said Lyft also takes a twenty percent commission. However, newer Uber drivers are paying even more; Mayer said Uber is taking twenty-five percent of his commission, and many new drivers writing on UberPeople.net corroborated that claim. This commission raise for new drivers has been playing out in other cities across the nation as well, as Ellen Huet of Forbes reported in September. In Chicago, this means that many of the drivers signed up under Uber’s South and West Sides initiative will pay the twenty-five percent commission. Uber also does not allow passengers to tip in the app, while Lyft does.

Uber keeps its fares low partly because the company doesn’t pay for car maintenance and complete insurance. But Uber drivers still eat that cost, since the wear on their car from Uber driving eventually catches up with them. One user on Uberpeople.net, S_hicago, wrote in response to a request for sources, “That’s the biggest problem for any driver. The hidden cost of depreciation that you won’t notice for a while if you don’t realize it’s there. You could dig yourself a hole for two years without ever realizing it.” According to Mayer, who is highly critical of the company despite driving for it, when Uber advertises high earnings to its drivers, they often use figures that imply gross revenues, rather than revenue after expenses.

Uber is also often criticized (usually by taxi drivers) for having questionable insurance policies. The company provides liability insurance for UberX vehicles while the Uber app is on, but Mayer said that many of the insurance policies Uber drivers have themselves don’t support vehicles that are ever used for ridesharing services. Some insurance companies have canceled policies after finding out that their clients are rideshare drivers after an accident, according to a PolicyGenius article from last year. Recently, some insurance companies have created policies that cater to rideshare drivers; Uber has partnered with the insurance startup Metromile to offer one. Mayer was able to get a fairly inexpensive one of these policies from Liberty Mutual, which was more cost effective for him than Metromile, but he estimates that many other drivers still don’t have this insurance, since Uber doesn’t require it.

Despite saying it had been more difficult to maintain earnings recently, reporting struggles with a new update to the Uber app, and claiming that “Uber isn’t what it used to be,” the Uber/Lyft driver who spoke to the Weekly still had good things to say about Uber.

“I like being my own boss and having the freedom,” he said. “There are certain things you have to give up for freedom.”

S_hicago from Uberpeople.net said these financial concerns end up affecting where Uber drivers go. In S_hicago’s view, while service to the South Side needs to be addressed, it’s not just about particular drivers not being willing to work in the area.

Uber has certainly expanded service to the South Side, and there’s no denying that racism and discrimination can have an ugly influence on both taxi and Uber service. Yet in the debate about how to sustainably and fairly solve the problem of equitable service to the South Side, it is important to consider the fact that many taxi and Uber drivers, including those from the South Side, are working to pay off expenses and make a living in a difficult climate.

“I would have zero problem driving the South Side,” wrote S_hicago. “There’s just no money to be had. Read or write whatever socioeconomic story you want into that.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article referred imprecisely to which personal liability policy Gersh Mayer has. His personal liability policy is from Liberty Mutual.

I am an Uber driver and love it when I get a drop off in Hyde Park or the Southwest Side. Problem is, that rarely happens. I live on the West Side and I have to get to the near north before I get steady business. The last line of the article is correct, there is no race element to this discussion, it is simply economics. Higher population density equals more rides. If I want to make money doing UberX, I have to keep my car full of passengers. Otherwise, I’m running my car into the ground at my own expense.

Point of clarification: The personal liability policy I have is from Liberty Mutual. The Metromile premium wasn’t quite cost effective for me and I’m leery about working with a relatively new operation that’s being touted by Uber. Uber recently severed ties with a financing program run by Santander, a Spanish firm under scrutiny for predatory lending. One can’t be too careful about signing on the dotted line around here. Uber drivers are occasionally required to sign off on legal documents which are sometimes impossible to download but the app won’t operate if you don’t sign off.