Patricia Frazier’s Graphite opens with a quote from fellow poet Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, excerpted from a passage reflecting on the Williams sisters. Rankine says Serena and Venus are “graphite against a sharp white background,” a stark contrast to the accepted homogeneity of professional tennis.

In Frazier’s book, her grandmother is given the name “Graphite” and is the book’s lodestar: several poems are given over to exploring her life—and death—despite her being “Black,/and erasable.” The graphite (in lowercase) metaphor also permeates the rest of the book, laying bare how Englewood and the Ida B. Wells Homes, both places where Frazier grew up, are shunned by those too frightened of violence to see the beauty and community Frazier has experienced. In her poems, Frazier elevates these histories, printing them in ink, committing them to permanent record. Her poems are intimate, spilling secrets and printing photos of places no longer there.

Frazier is a literary wunderkind—she turned twenty this year—who was first appointed Chicago’s 2018 Youth Poet Laureate and then ascended to the national title after competing with other finalists in New York. She studies cinema arts and sciences at Columbia College and is also an organizer with Assata’s Daughters, an intergenerational collective of Black women based in Washington Park, named after radical Black activist Assata Shakur. She grew up in the Ida B. Wells Homes public housing project until its buildings were vacated in 2009, and her family moved to Englewood. Graphite is her first book; it’s preceded by work in Chicago magazine, Vogue, and the Weekly.

While I read this book—as a West Coast transplant, not Black, having to look up slang online—the words felt like privileged information, a precious viewpoint; not only because of the frank documentation of teenage life (in the dedication, Frazier apologizes to her grandmother for “everything you’ll find out in this book”) but because the places and people Frazier writes about are so often shoved aside—by City services (“Rahm does/what Daley did to my sister Hyde Park another/gentrified Black girl gone”), by Chicago “northside neighborhoods [who] get to call their violence inter-communal,” by politicians nationwide who vilify the South Side while never having stepped foot in Englewood or the State Street Corridor (“nobody asks me for consent/before taking my name to make Chicago/the martyr they need her to be”).

One of the first poems in Graphite is “Auditioning for the Role of Child with Teen Parent,” an ode to Frazier’s mother. Frazier contrasts MTV’s Teen Mom with her own home life, telling the reader “y’all late, I thought my Mama was badass before Kylie Jenner did it.” She also hits against stereotypes, asking, “what if she’s a teenage mom and this is still a story about Black/excellence?”

As the book progresses, the poems shift to focusing on place and community. Back to back are “A Poem for Englewood” and “Englewood Teaches a Lesson in Pronunciation.” The former sets up the latter by breaking down the definitions—and official dictionary pronunciations—of “engle” (“to cajole or coerce”) and “wood” (“an area of land covered with growing trees”), reflecting on the meaning of their compound. The conclusion? “Englewood the bloody name nobody wants to have, but everyone wants to hold.” This line underscores Frazier’s criticism of how Englewood and the city’s housing projects are portrayed in media—not just by mainstream news outlets or calls pointing to “Chiraq” as a national den of gun violence, but also by the “white kids…beatboxing my name in their poems.” This justified anger pulses in every page.

Reflecting on her work in an interview with Chicago magazine, Frazier says “Normally when people want to go back to where they’re from, they can go back to a house, or a specific place like a store or building where they spent their childhood. But I can’t. There are no buildings I can go back to.” Frazier writes about how fast kids had to grow up in the projects, their aging accelerated by issues like teenage pregnancy—“lighter fluid to a childhood.” At the same time, many of the moments she describes are full of childlike wonder (“sucking our fingers/free from hot Cheeto/crumbs/bumping entire albums/of slurping/and smacking lips”). Frazier is honest in her assessment of life at the Ida B. Wells Homes, mixing nostalgia for the now-demolished buildings with memories of the lives and deaths of its residents. While their physical presence might be gone, the Wells Homes live on in Frazier’s work, the printed words unerasable.

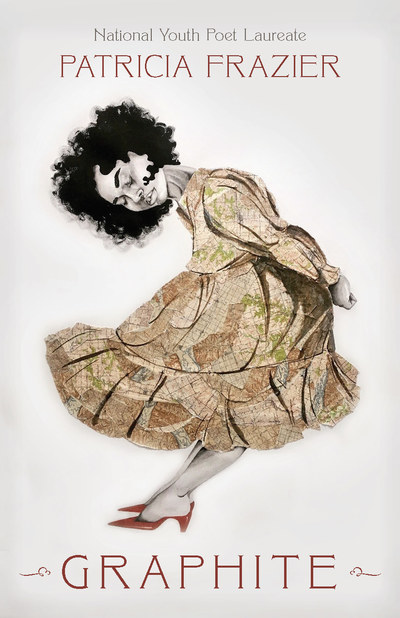

Patricia Frazier, Graphite. $10. Haymarket Books. 44 pages.

Jasmine Mithani is an editor at the Weekly. She last wrote about calling “Sloop” home.