In late March, Jonathan López, an undocumented immigrant from Little Village, went to the United Center to get his first vaccine. He said he had spent almost every day of the month calling the operation’s call center to make an appointment. When he finally got through, he found out he was eligible as a resident in the 60623 ZIP Code, one of many ZIP Codes currently being prioritized by the City for vaccination.

Protect Chicago Plus is the campaign guiding the city’s vaccine distribution. Officials rely on data from what they call the Chicago COVID-19 Community Vulnerability Index (CCVI) to rank neighborhoods based on their level of exposure and vulnerability to COVID. Rankings range from four (lowest vulnerability) to sixty-four (highest vulnerability). Through Protect Chicago Plus, the city has been announcing vaccine eligibility by way of ZIP Codes over the last two months.

Many people in Latinx and immigrant communities say they are finding information about vaccine availability not only through official sources, but through word of mouth and community-based organizations that are doing bilingual outreach independently. While this may be more effective than showing up to a mass vaccination site and testing their luck, there are still challenges with this approach—namely, that outreach to Spanish-speaking communities is not uniform, and it relies on under-resourced groups to do the heavy lifting.

López has lived the majority of his life in the U.S. and has been educated here. And while he can speak and write English, he didn’t see signs in Spanish or other languages at the United Center.

“Because this is a mass vaccination site, I think better directional signage is needed in multiple languages,” he said. “I only saw one person with an interpreter sign on their ID, but even that was also in English.”

As of March 29, there have been 225,127 known COVID-19 cases in Illinois for people identified as “Hispanic.” At the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, Latinos statewide surpassed all other ethnic groups in the total number of reported COVID-19 infections, according to data from the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH).

After he got his vaccine, López took out his phone and snapped a selfie to post to social media “to show friends and family how easy and painless it is to take the vaccine.” But a security officer approached him, demanding he unlock his phone and delete the photo without offering an explanation. “I’m an undocumented immigrant so I just did not argue,” López said.

Although he felt the process inside was “smooth” and the U.S. Army soldiers administering the vaccines were “efficient,” he didn’t think it was a place where immigrants could find help. “It’s not a friendly place for non-English speakers.”

Luvia Quiñones, health policy director for the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights (ICIRR), said that her organization has had to create materials in various languages to educate immigrant communities about the vaccine and keep people up to date. But she is also concerned about the lack of computer and internet access in immigrant communities. “They may not know how to use [a computer] either or how to navigate government-related websites.”

It took almost two months for Elena’s (whose name was changed to keep her identity anonymous) ninety-two-year-old father to get vaccinated. Elena helps care for her father, who lives in Little Village, and has been the point person in helping the rest of her family understand the pandemic. While her dad is able to get around, Elena said he requires assistance.

Since older adults became eligible for the vaccine, she had been calling various numbers but said it’s been difficult to get through. One of those numbers was for McCormick Place, which she heard about through one of the local Spanish-language TV stations, but she could not get through. Elena also heard about a vaccination site at Arturo Velasquez Institute on the news, but when she showed up she was referred to a website to make an appointment.

A lot of her frustration came from busy phone lines and being unable to speak to a human being. “There was a machine talking in English on the other side, and you couldn’t talk to anyone.”

Navigating the internet for vaccine information hasn’t been easy either. Elena cannot recall which website, but she said one of them asked for her father’s insurance information. She didn’t have that information at hand. “I really don’t know why they are even asking for that if they say it’s free,” she said.

Elena finally got a number that led her to Esperanza Health Center in Little Village. She was helped by a “promotora,” or community health promoter, through the community-based organization Enlace Chicago. Her father was able to get his first dose there and will get his second shot in April.

She asked for a vaccine for herself because in addition to her father, she also cares for her elderly mother-in-law. But because she lives in Cicero, a majority-Latinx and immigrant Cook County suburb where people have also been struggling to make appointments, they told her she was not eligible to be vaccinated in Chicago.

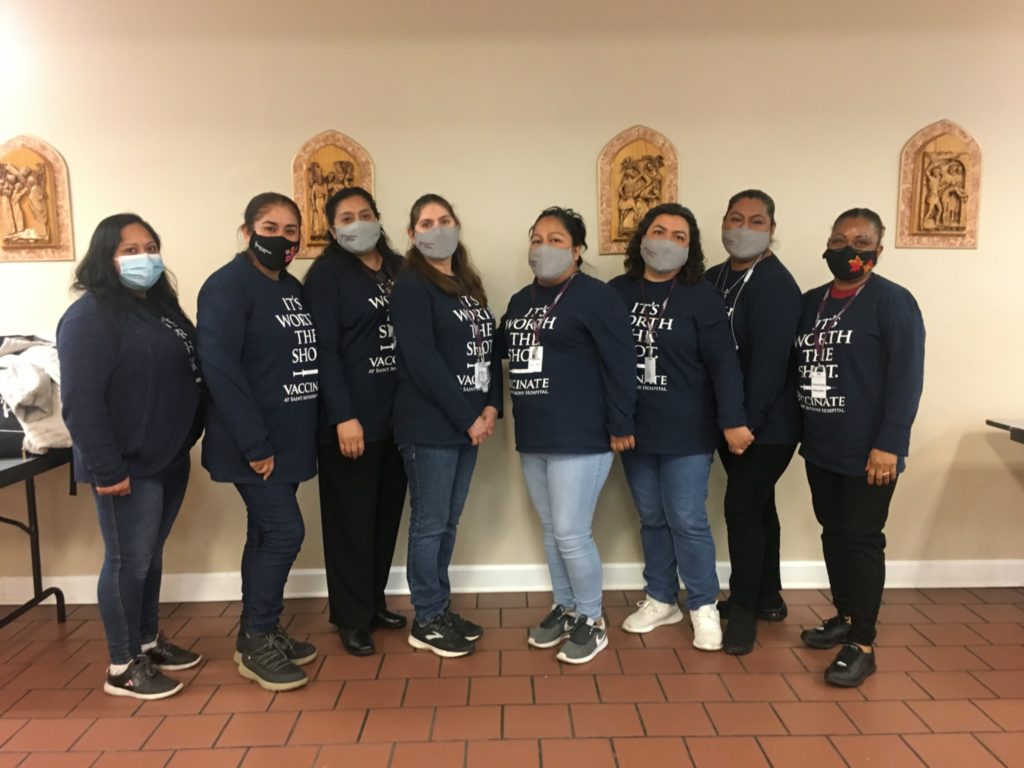

Across the street from St. Agnes of Bohemia Catholic Church, in their Cuarto Manz Hall, promotoras were helping Latinx and immigrant residents sign up for the COVID vaccine on Thursday, March 25. Promotoras like Jackeline Ortiz took down people’s personal information to help them schedule an appointment with Saint Anthony Hospital. Ortiz said the information is given to bilingual representatives from Saint Anthony, who from 8:00am to 7:00pm daily call people to confirm their appointments.

Ortiz volunteers at Telpochcalli Community Education Project (TCEP) in Little Village, where she got connected to a volunteer opportunity promoting health services to the community for Saint Anthony in 2019. When the pandemic hit, she had to pivot. Now she works to educate people about the vaccine by going to laundromats, corner stores, and small businesses in Little Village. She promotoras are able to earn a small stipend doing this.

“Some people have asked if the hospital will share their information with ICE if they are looking to deport someone. So we tell them the hospital can’t, because medical information is confidential,” she said. On December 10, 2020, Illinois Department of Public Health Director Dr. Ngozi Ezike said in a press conference that residents’ personal information, including immigration status, will be protected.

According to David Louridas from the Pilsen-based non-profit The Resurrection Project, which partnered with St. Agnes and the hospital, said 331 people were helped that day, and they have done about ten similar events guided by Protect Chicago Plus. “People were lining up at 2:00pm but the event began at 5:00pm. This tells you a lot about the need and the interest in the immigrant community to get vaccinated.”

At 7:00pm, as the promotoras were wrapping up, a man in his fifties was on his way out. He smiled and waved his baseball cap at the promotoras: “Gracias, gracias.”

“It’s very important to have events in places that the community knows and where they feel comfortable going,” Louridas said.

However, the assistance of city and public health officials has been a long time coming, and aldermen and community groups have had to organize vaccination events themselves.

Thirty volunteers of Mi Villita Neighbors organized the first vaccination event in Little Village, in partnership with Walgreens and the community nonprofit Padres Angeles after they saw that as of February nothing was being done in the area, which has a high percentage of essential workers and is at the top of the list of COVID deaths.

“The idea that we’re going to systematically vaccinate people by having these pop-up sites that are hard for people to find out about and then harder to register for doesn’t work,” said Dr. Howard Ehrman, a public health advocate, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and a member of Mi Villita.

25th Ward Alderman Byron Sigcho-López introduced a resolution on March 24 calling on the City to establish community and workplace vaccinations. Community vaccinations would take place in public places familiar to residents such as libraries, park districts, fire stations, and schools.

The proposed ordinance is based on a public, rather than private, model. “The public health model is you go out to the people. You hire people as public health employees. And you take the vaccine to the people in their schools, their churches, in their homes and apartments and in the workplace,” Erhman said.

“Only when we have a driven process through CDPH, and not by private entities, we are going to have changes,” Sigcho-López said to CDPH Health Commissioner Dr. Allison Awardy, during a Health and Human Relations Committee on March 25.

López was referring to the city’s vaccine dashboard, which shows that people in white neighborhoods are getting vaccinated at a significantly higher rate than people in Black and Latinx neighborhoods. For instance, while West Englewood appears as the most vulnerable neighborhood in the City’s COVID Vulnerability Index, and is eligible for a vaccine, it only shows 17.7 percent vaccinations as of March 30. But the Gold Coast, which is not eligible for a vaccine under Protect Chicago Plus, shows 32.1 percent vaccinations.

The resolution is backed by Ald. Rossana Rodríguez Sanchez (33rd), Ald. Daniel LaSpata (1st) Ald. Jeanette B. Taylor (20th), Ald. David H. Moore (17th), Ald. Ariel Reboyras (30th), Ald. Howard Brookins, Jr. (21st), Ald. Carlos Ramírez-Rosa (35th), and Ald. Maria E. Hadden (49th).

Ehrman, who used to be assistant commissioner at CPDH and served as chief medical officer in Will County during the Ebola outbreak, thinks Mayor Lori Lightfoot could have taken the federal funds the city received in the last year to rebuild the public health department. “They’ve done exactly the opposite. They have spent almost every cent on privatizing things that have completely failed,” he said.

The proposed ordinance is a combination of a jobs bill and a public health bill, said Ehramn, who, along with other public health advocates, has been working on the resolution. The proposed ordinance advocates for the creation of 2,500 CPDH jobs and would give $12 million to community-based organizations to hire 200 culturally competent health workers who would educate, organize, and help people get their shots. Unlike promotoras, who mostly volunteer for free or a small stipend, these health workers, also from Black and Latinx communities, would earn minimum salaries of $20 an hour for full-time work and be eligible for full benefits and union membership.

Meanwhile, insufficient outreach has left predominantly Latinx neighborhoods on the far Southeast Side feeling left behind. In April 2020, South Side Weekly reported that people in these neighborhoods are far more likely to have asthma because of their industrial surroundings. And since COVID-19 is a respiratory disease that causes pneumonia, pollution can make things worse. “If you live in an area where the air quality is poor, your lungs are already going to be stressed, so you may be at higher risk of COVID-19,” said Dr. Susan Buchanan, clinical associate professor of environmental and occupational health sciences at the UIC School of Public Health.

Eduardo, thirty-three, is an undocumented immigrant working at a metal scrap yard in East Chicago, Indiana; his name has been changed to protect his identity. Customers approach him to sell non-ferrous metals like aluminum, nickel, lead, tin, brass, silver, and zinc. He said he sees about fifty people per day who come in to recycle their metal.

Eduardo lives in Hegewisch and has a wife and four children. Between March and June of 2020 he was unemployed when his workplace had to close due to COVID. Because he is undocumented, he was not able to apply for unemployment and did not receive any stimulus payments. He picked up food from his children’s school through the Chicago Public Schools’s Grab & Go meal program almost daily. He also used up his savings to pay bills and buy groceries.

He said he doesn’t know where to start when it comes to finding a vaccine. Only 2, 011 people have gotten a vaccine in Hegewisch as of March 29, out of the almost 9,000 residents in this ZIP Code. He knows 60633 isn’t part of Protect Chicago Plus yet, but even if it was, he would not know where to find information, where to go, or who to ask.

He said he searched on ZocDoc, the city’s main platform for eligible Chicago residents to find vaccine appointments, under the belief that because he works in manufacturing, he would be eligible for the vaccine. But he wasn’t able to find any available appointments.

Ana Guajardo, executive director of Centro de Trabajadores Unidos, a workers’ rights organization in the East Side that also reaches out to Indiana border cities near Hegewisch and the South suburbs, said she’s not surprised ZIP Codes in the area are not yet included under Protect Chicago Plus.

“I’m glad communities like Little Village, Gage Park, Back of the Yards, and others are eligible. But why not us?”

The East Side ranks forty-four in the vulnerability index.

Like many other community-based organizations, Centro de Trabajadores Unidos has had to do the heavy lifting. They have informed their neighbors about the importance of getting vaccinated. Guajardo said she had to apply for a COVID-related grant to allow organizers at the center to work as “navigators” that disseminate information about testing, contact tracing, and vaccinations.

Alderman Susan Sadlowski Garza, whose ward encompasses the East Side, posted a flyer on her Facebook Page on March 23 with four locations open to people eligible in phases 1a and 1b in ZIP Code 60617: Chicago Family Health Center, Aunt Martha’s Health Center, JenCare, and Walgreens Pharmacy on Commercial Avenue.

Guajardo said that using WhatsApp has helped her keep the community informed not only about vaccination eligibility and appointments, but also for testing early on. “Initially, we started using WhatsApp to alert the community about ICE presence in the community, but we’ve expanded it to COVID too.”

From the mass vaccination site at the United Center, where information for Spanish speakers was not available by phone or on site, to St. Agnes of Bohemia in Little Village, where 192 have lost their lives to COVID, to the Southeast Side, with its long history of pollution, the vaccines remain difficult to access even with the city’s Protect Chicago Plus program.

López, who had wanted to show his friends and family that he got the vaccine at the United Center and couldn’t, said his mother tested positive for COVID in July and they had to discuss end-of-life plans.

While his mother recovered, she still has trouble breathing and a chest cough. “Knowing I live in a neglected and underserved community really affected me the most mentally,” he said. “I felt secluded and I knew that relying on the City to take care of us was not support I could count on.”

Alma Campos is a bilingual reporter based in McKinley Park. Her writing has appeared in Univision Chicago, WTTW, and Crain’s and focuses on immigrant and working-class communities of color in the South and West Sides. She last wrote for the Weekly about vaccinations at the City Colleges.