The only existing tape of the 1970 documentary Lord Thing was forgotten for decades until a single damaged VHS was recovered and restored by the Chicago Film Archives, only to be shown at select screenings across Chicago, including the Black Cinema House viewing I attended. Once the curtain rises, however, the inescapable magic of this gem of a film is finally revealed, and one is immediately sucked into the world of the 1960s West Side. A must-watch for any Chicago history aficionado, Lord Thing depicts a part of this city’s turbulent past that is not often told but remains relevant in its content as well as its grounded style.

While another director might have chosen to take a more distant, objective take on Chicago’s Vice Lords, DeWitt Beall does away with the impartiality of the documentary medium. Casting former Blackstone Rangers spokesman Leonard Sengali as narrator (the Rangers were allies of the Vice Lords), Beall recreates the personal stories told by individuals through staged vignettes featuring actual gang members in a style echoing the gonzo journalism of Hunter S. Thompson. Sengali is brilliant, refusing to simply read his lines in the monotone of the traditional chronicler, instead infusing his speech with the slang and frankness of the streets.

The plot of the film follows the history of the Vice Lords through the lives of several of its most prominent members, beginning in the streets of 1950s Chicago before the proliferation of guns. As racial tensions were clawing to the surface in Chicago, the young Vice Lords, then under the leadership of Eddy Perry, “got even” with the abusive Chicago police by warring with other black gangs on the West Side. According to Vice Lord Bobby Gore, this was part of a cycle of black-on-black violence perpetuated by powerlessness in the face of racist oppression, and deep down everyone knew it.

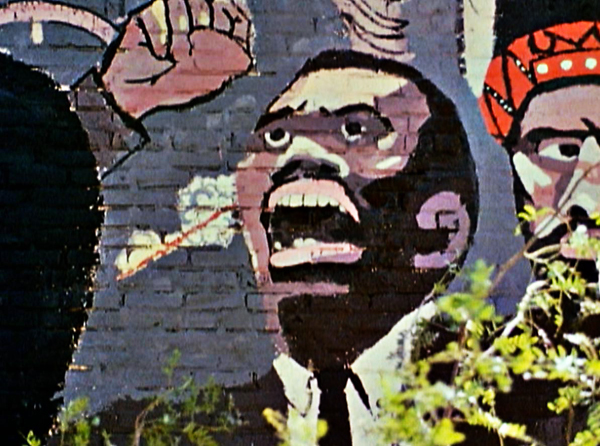

It was only after a series of riots in the mid-sixties that the Vice Lords and other Chicago gangs realized who their true enemies were and went through a radical shift in thinking about their rivalries. Black nationalism was on the rise in Chicago in the late 1960s, and the city’s gangs reimagined themselves as harbingers of this new urban consciousness, with the Vice Lords leading the charge. Within a few short years, the Vice Lords became the Conservative Vice Lords, who focused their efforts on community empowerment and self-reliance rather than petty gang enmities. In 1967, they became the Conservative Vice Lords, Incorporated, and they undertook an effort to create a strong, independent, socially conscious black community on the city’s West and South Sides and to defy the Chicago Police Department.

These activist-gang members built African-themed clothing stores, community currency exchanges, and civic institutions exclusively for their black compatriots, and by 1969 successfully forged a historic gang alliance between themselves, the Blackstone Rangers, and the Gangster Disciples to create what came to be known as the “LSD.” These gangs put aside their differences in order to fight white supremacy together for the first time since their inception. However, the city could only tolerate defiance to the status quo for so long, and by 1970, even though gang-related crime was at an all-time low, Daley launched a war on gangs in retaliation, leading to a final, enormous, showdown between the powers that be and the movement that the Conservative Vice Lords had helped create.

At the conclusion of Lord Thing, the small, packed screening room of the Black Cinema House erupted into applause. Present at the subsequent discussion panel was former Vice Lord gang leader Benny Lee, the head of the National Alliance for the Empowerment of the Formerly Incarcerated, who vividly connected the dots between the legacy of the Vice Lords and the fractured gang scene of today. Lee, like a fiery preacher, recounted the fate of the Vice Lords at the hands of the Daley machine and discussed his multiple stints in prison and the de facto enslavement of poor minorities through the leasing of convicts to multinational corporations as free labor, as well as the plight of disenfranchised ex-felons. He also challenged the crowd: “I know you’ve got plenty of prison stories, but do you have a successful re-entry story?”

The last scene of the film shows gang leader Bobby Gore returning to his neighborhood after being released from prison, where he encounters a young boy with a red beret on. The boy surprises Gore with his militancy, demanding a continuation to the fight to bring adequate housing, healthcare, food, education, and security to the underprivileged neighborhoods of Chicago. Forty-four years later, the plight of minorities in Chicago remains largely the same—the inequities articulated by the young radicals in Lord Thing still plague low-income communities across the West and South Sides. While it is unlikely that a united, socially relevant, gang-led movement will ever arise again in the Second City, Lord Thing shows us a glimpse of what could have been.