Afifty-five-inch flat-screen TV framed Abdul Alkalimat, Romi Crawford, and Rebecca Zorach, the three editors behind The Wall of Respect: Public Art and Liberation in 1960s Chicago. It stuck out—not because of its sheer size, but because it was a backdrop providing a constant reminder of the event’s purpose: the importance of visibility.

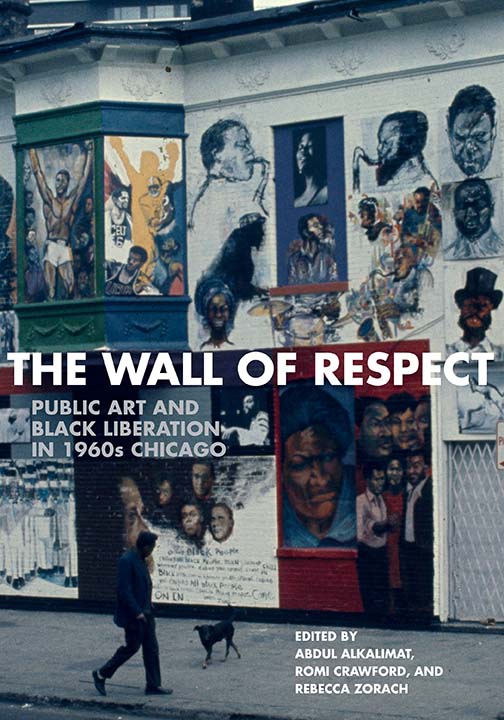

The book release and panel discussion, moderated by Northwestern University Press editor-in-chief Gianna F. Mosser and hosted by the Center for the Study of Race, Politics, and Culture at the University of Chicago on November 9, celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the inauguration of the Wall of Respect—a mural that once stood on the side of a building at 43rd Street and Langley Avenue in Bronzeville. The event followed an exhibit on the Wall, curated by Alkalimat, Crawford, and Zorach, that ran from February to July at the Chicago Cultural Center.

Mosser started the event by asking Alkalimat, an activist and founding chairperson of the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC), what historical events in the 1960s led to the formation of OBAC and the creation of the Wall of Respect.

“I have a lot to say tonight,” he said. “But I first have two things to say. How many people here actually saw the Wall?” A few hands shot up from the audience.

“Second thing,” he said, looking over to those raised hands. “A very important cultural figure in the history of the arts of Chicago is here tonight. A dancer, who brought the African diaspora home to Chicago. I want you to give a round of applause to Darlene Blackburn.” Blackburn, a Chicago dance instructor who appeared on the Dance section of the Wall, smiled from the audience.

Alkalimat then delved into timeline that led to OBAC’s creation of the Wall: the March on Washington and the Chicago Public Schools boycott in 1963, the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, and the emergence of Black Power in 1966.

The Wall was visual representation in a time when positive African American imagery was seldom found on billboards or recognized in the mainstream art world.

“There was activism, poetry, and this sort of being present and around the Wall,” Crawford, a professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, said as she flipped through images on the TV screen. “It was a site and locus for community activity all the time, and community members that were engaged in a diverse set of art practices.”

The Wall is not widely acknowledged in mainstream discussions even though it united dozens of artists, and, as Alkalimat put it, “brought people out of their studios and created a community of artists who felt responsible to each other.”

In spite of the Wall’s undervalued impact on today’s discussions about public art, photographic evidence like that in the book illuminates the Wall’s existence and broadens conversations. Packed with photos curated by Crawford, The Wall of Respect is a study of pieces of memories coming together. Without photographs, much of the discussion surrounding the Wall would not exist.

“The Wall is one of the few murals that has photography articulated and embedded into it,” she said. “The photographs reveal pertinent information about the Black liberation struggle. They give us cues to the kind of ways of being, in a vernacular sense, for some of the Black community that were the educators, artists, and conceptualists of the Wall—and also the people from the neighborhood.”

Because the mural depicted real people from real photographs, the community was able to connect to it.

One of the main goals of both the Wall and the event was to give name and presence to Black community figures erased by mainstream media. Crawford made a point during the event to name the photographers of the Wall who never had a chance to display their work in galleries: Billy Abernathy, Darryl Cowherd, Robert Sengstacke, Roy Lewis, and Onikwa Bill Wallace. They were Black photographers capturing Black experiences. Although their images are static, the everyday life the community found in them—and the interaction between their different styles—makes them feel alive.

The Wall included seven sections—Statesmen, Athletes, Rhythm & Blues, Religion, Literature, Theater, and Jazz—worked on by fourteen different artists. In display, it became a place of performance. Poets such as Alicia Johnson and Gwendolyn Brooks performed their work at the Wall. And not all the people depicted on the Wall were celebrities, Zorach noted. While most figures on the Wall were well-known nationally—like W.E.B. Du Bois and Malcolm X—many were widely unknown in the mainstream media, such as Blackburn, who shared African and Afro-Caribbean dance with Chicago Public Schools, and young Muslim women praying.

“They reflect the heroism of the ordinary person in the community,” Zorach said.

The structure of The Wall of Respect mirrors this visual structure. Poetry by Brooks written in dedication to the Wall, primary documents illuminating the founding of OBAC, interview transcripts with one of the lead muralists, William Walker, and photographs complementing the text are weaved throughout the 376-page book, similar to how different sections of the Wall, although embodying individual artistic styles, were woven together cohesively.

But as much as the Wall created a collective unity of artists and thinkers, it also caused controversy. Alterations were made to the Wall in later years, reflecting changing political sentiments. One significant alteration was the addition of a Ku Klux Klan figure.

“Rebecca has a slightly different take of this, and I support it, but I maybe support my take—which is that there was wrong done,” Alkalimat said. “It became the Wall of Disrespect.”

In the section of the book exploring responses to the Wall, Zorach writes about a “key moment of strife” during the Wall’s life. Walker allowed neighborhood residents to whitewash Norman Parish’s “Statesmen” section, so Eugene “Eda” Wade placed a KKK figure on the Wall.

“I’m not trying to defend his actions,” Zorach said. “But in some ways, it did open the Wall up to a different kind of change and involvement by people in the community.”

“Critical revision is an important part of the Wall,” Crawford added. “It makes it unlike any other works, even though it began in that beautiful moment of collective consensus of what it should be.”

Even though the Wall was torn down after a fire in 1971, it lives on in memory.

“The Wall lives on in community engagement art,” Crawford said. “I find myself bringing it up a lot to contemporary practitioners; so many don’t know about the Wall. It’s really useful to the current generation of artists.”

It lives on, also, in a single physical piece. The only part of the Wall remaining today, Crawford said in reply to a question near the end of the event, is a photographic piece of Amiri Baraka (formerly known as LeRoi Jones) captured by Darryl Cowherd. Cowherd returned to the neighborhood in a state of distress after five years in Sweden, and he had a strange feeling—so he put up a ladder and took the piece down.

The Wall’s location, 43rd Street, was considered downtrodden by outsiders, but was also known as “Muddy Waters Drive” because of its reputation as a gathering place for blues musicians.

“It was a cared-for location even though it was a forbidden zone,” Crawford said.

It continues to be cared for—and to be seen. While the Wall is no longer physically visible, the memory of its impact found in the people, the images, and the event provides a backdrop for a future lying in wait.

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly