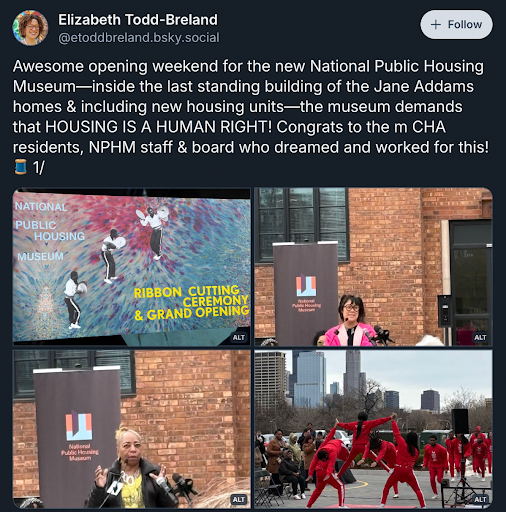

At the corner of Ada and Taylor Streets, where the wind whips between century-old brick and modern glass, the grand opening of the National Public Housing Museum (NPHM) drew an eager assembly in April. Former and current public housing residents from Cabrini-Green and Altgeld Gardens, city officials, media, and curious Chicagoans gathered to celebrate what had been years in the making.

The National Public Housing Museum occupies the last standing building of the Jane Addams Homes, which were closed in 2003 as part of the Chicago Housing Authority’s (CHA) sweeping Plan for Transformation.

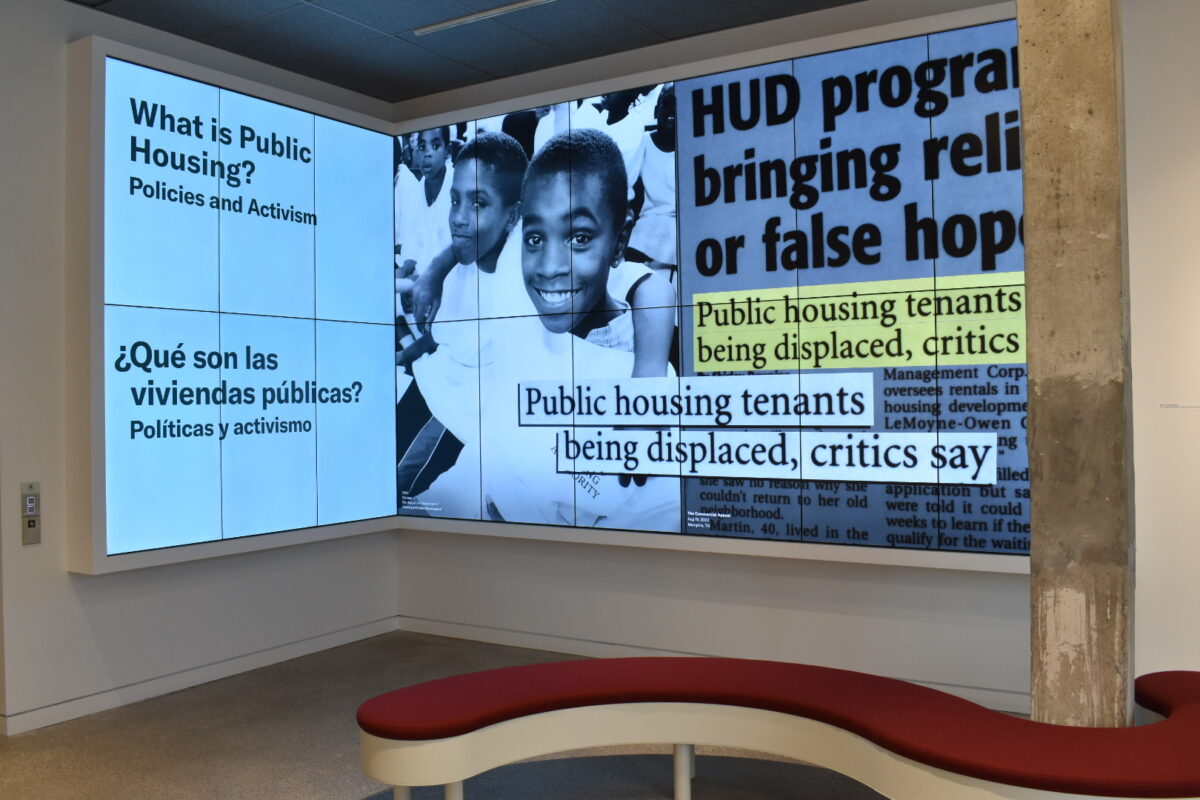

The museum preserves artifacts of America’s intricate relationship with public housing and actively challenges a national debate that has long erased the experiences of those who called these developments home.

With nearby construction signaling another wave of neighborhood transformation, the museum has positioned itself as a resistor—a cultural witness that refuses, even amid federal hostility to its mission, to separate its exhibits from the urgent questions of who deserves housing and whose stories deserve telling in America today. The museum is part of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, whose members are devoted to preserving the memory of painful historical events against censorship.

“This is a very important time to continue to tell the truth,” said Elizabeth Todd-Breland, associate professor of history at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). Todd-Breland was one of many who celebrated the long-awaited opening of the museum. She also actively invites her students to explore the museum as a living classroom—a place where housing policy, racial justice, and community organizing intersect beyond textbook theories.

Todd-Breland has engaged with the museum’s programming in multiple capacities, particularly through the Beauty Turner Academy of Oral History, named after the longtime journalist, activist, and Robert Taylor Homes resident, which trains current and former public housing residents to document their communities’ histories through oral storytelling. In fall 2024, she brought these perspectives into her “Urban Renewal and the Archive” course at UIC, which examines the history of urban redevelopment with special focus on Chicago’s Near West Side.

Todd-Breland described a particularly meaningful event where the museum created an interactive experience at the Little Italy library. The staff brought an enormous map spanning several tables, marked with pins indicating locations where oral history contributors had lived. Participants—including neighborhood residents, former public housing residents, and local students—listened to these recorded stories together, creating an immersive engagement with oral histories.

This collaborative process of public memory impressed Todd-Breland enough that she invited Liú méi zhì huì, senior programs manager of the museum’s Oral History Archive & Collective, to bring the mapping activity to her classroom. Following the presentation, she took her students on a walking tour from UIC’s campus to the museum site, allowing them to physically interact with spaces they had been studying. The class concluded their experiential learning session in the garden adjacent to the museum, connecting academic study with place-based understanding as the museum’s educational philosophy encourages.

While Todd-Breland has incorporated the museum into her academic curriculum, other visitors have found the space valuable as a point of comparison to national institutions.

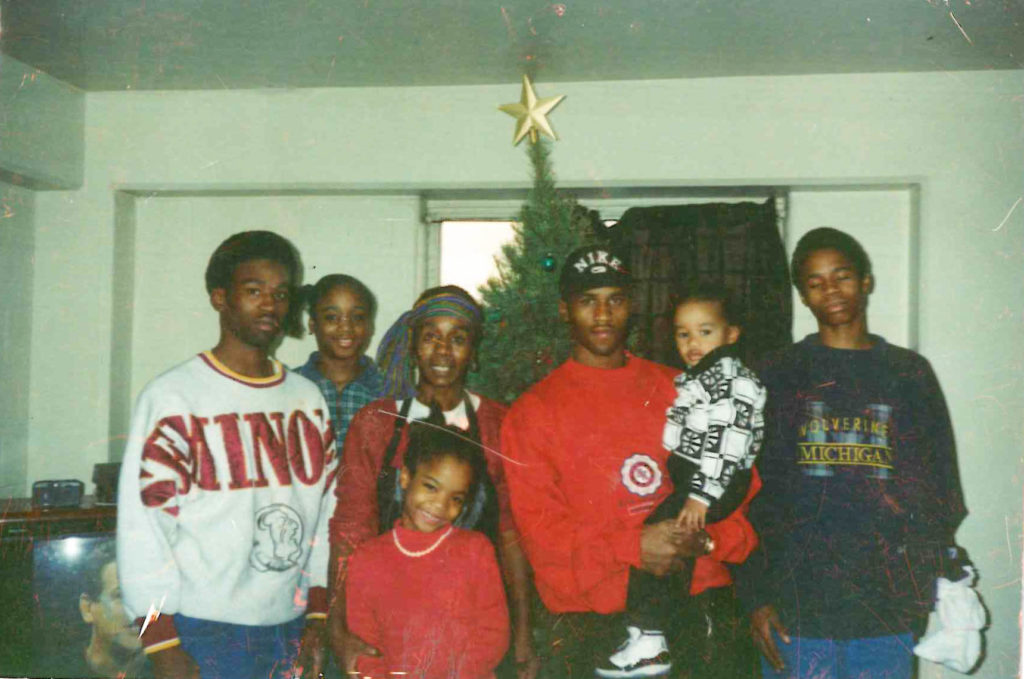

Among the crowd that day, John Halloran, associate professor and co-program director in the department of social work at Lewis University, reflected on the museum’s distinctive methodology. “We took our two daughters to Washington, D.C. for spring break this year, and we went to the National Museum of African American History and Culture and to the National Museum of the American Indian—which both have a real social justice focus—and it was really a great way to see how different stories get told and to think about what message a place is trying to send. At the NPHM, the message I kept returning to was ‘people lived here; this was their community’.”

Halloran emphasized the NPHM’s deeply personal nature, noting how effectively the museum connected physical spaces and objects to the actual lives and experiences of residents. He observed that discussions about history and policy often become impersonally abstract, whereas the NPHM’s particular strength lies in creating an environment where visitors can tangibly sense the humanity and lived realities of those who once called public housing home.

This sense of belonging is woven into the museum’s foundation. As guests step through the doorway of the building, they’re greeted not with the usual museum formalities but with personalized welcomes that immediately reframe their relationship to the space around them.

“Welcome home,” said Dorian Nash to a former public housing resident who had lived in the Jane Addams Homes. It was their first time coming back to the building since it had turned into a museum.

Nash oversees the museum’s innovative workforce development program, explaining that it’s about “trying to find and seek great people within public housing and teach them a new skill…help them to build upon their careers.”

The NPHM has quickly established itself as “the nation’s largest archive of the stories of public housing residents,” featuring these narratives in podcasts, exhibits, research, and scholarship. The museum includes the Dr. Timuel Black Recording Studio and dedicated spaces for programs that address the racial wealth gap and create a cultural workforce that diversifies the museum profession.

Nash puts her own spin on workforce development by building on this foundation, ensuring that public housing residents aren’t just subjects of the museum’s exhibits but active educators, shaping how their stories are shared. She brings valuable experience from her previous position at the Smart Museum, drawing on her background in theater, programming, and education to structure the NPHM’s ambassador program. These staffers go through a paid three-week training to lead tours and other outreach efforts. She calls the team “educators” rather than “docents” because “I want them to own that in this work…I’m educating you about my lived experiences. I’m also educating you about public housing.”

Inside an Archive of Resistance

The NPHM stands out among cultural institutions for two uniquely intimate exhibits that place lived experiences at the center, connecting visitors to real families who once called these units home.

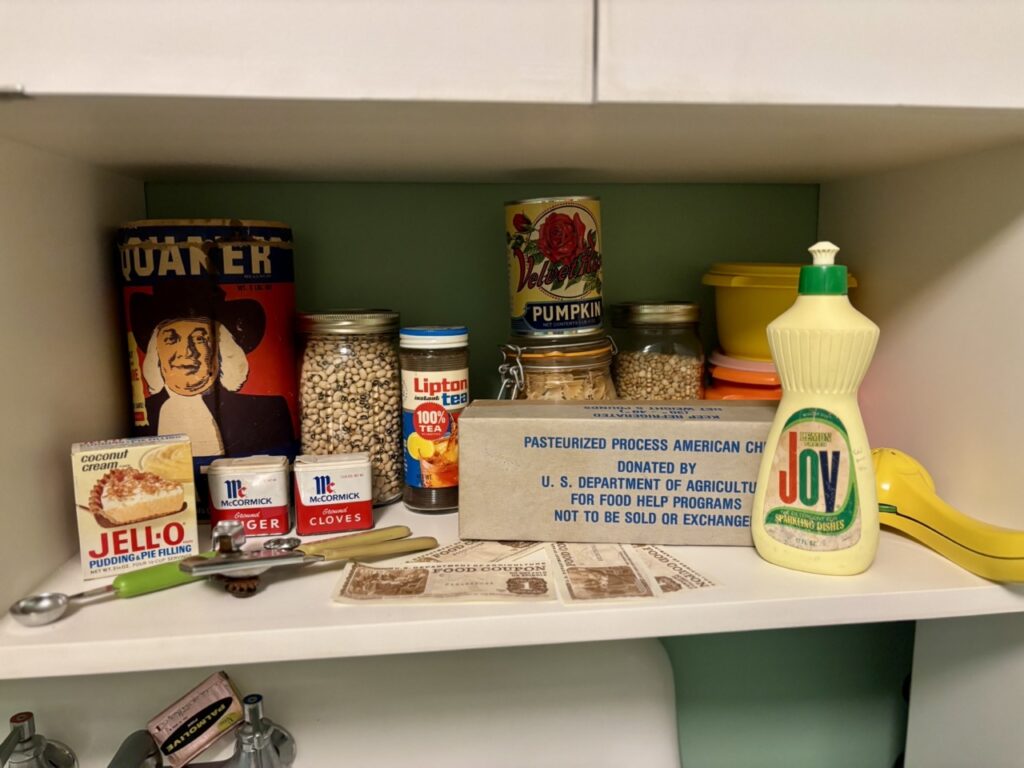

In a recreation of the Turovitz apartment from 1938, visitors encounter authentic artifacts like a treasured gefilte fish chopping bowl—a simple kitchen tool that carried deep cultural significance for this Jewish immigrant family who escaped antisemitism only to find themselves speaking Yiddish in a new country, unable to read or write in English.

Moving through time to the 1960s Hatch family apartment, visitors witness the material evidence of the lives of Reverend Hatch’s family of ten (seven girls and one boy)—copies of Ebony and Jet magazine, a light-up Jesus portrait on the wall, treasured recipe cards for “Helen’s Surprise”, a large antique color TV, period furniture, and an apartment made up of two units the housing authority combined to accommodate them.

The tour brings these stories to life not just through audio commentary from Chicago actor Lil Rel Howery, but through the museum’s use of interactive headsets that allow visitors to hear directly from family members as they move through the spaces, creating what Nash calls “seven performances a day.”

Nash manages a team of seven ambassadors, noting that this program helps them feel they “belong in this space,” since “museums typically can be very clinical and not approachable, but by them having a piece and a stake in what is being said and how the tours are ran, it is more of a belonging.”

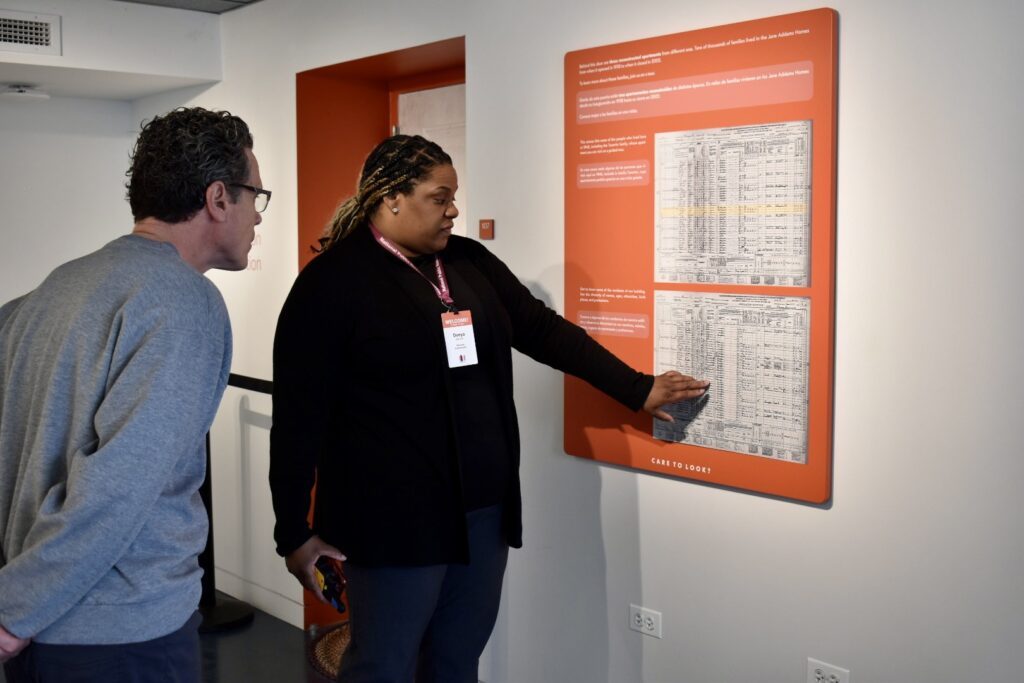

One ambassador, Donya Robinson, embodies this philosophy as she guides visitors through the historic apartments, sharing stories of families who once called these units home. Her presence represents the museum’s commitment to prioritizing employing those with direct lived experience of public housing, transforming what might be abstract policy discussions into deeply personal testimony. Robinson moved confidently between artifacts, occasionally pausing to add her own insights.

“I’m a current public housing resident. I live right now in the Dearborn Homes, right here in Chicago, Illinois. But to my ignorance, I just thought public housing was for poor Blacks or African Americans,” Robinson explained. “I joined a job program in my area and I saw it at the museum. I got in the training program, and luckily, as you can see, I landed the position. But I learned so much, and I’m glad that I’m able to share what I’ve learned with you all here today. What I learned too is that African Americans actually had to fight their way into public housing, right?”

She explained to a group of five visitors that veterans returning from war frequently encountered obstacles securing affordable housing despite their military service. She was equally surprised to learn about the housing barriers faced by Jewish families. These historical revelations transformed her perspective on public housing’s complex history and the diverse groups who struggled for housing access.

Guided by former and current public housing residents, visitors transition from passive observers to honorary residents, embodying what Nash describes as “radical hospitality practice”, which goes beyond basic customer service to make people “feel more welcome, to make them feel at home.”

An Old Deal Erased

The New Deal’s vision for public housing emerged as a direct response to the crushing poverty and housing instability of the Great Depression. Through the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the federal government made an unprecedented commitment to ensuring that Americans had access to safe, affordable housing as a matter of national policy.

Robinson explains to visitors that residents who moved into early public housing units like those in the Addams Homes, constructed in 1938, often came from overcrowded, unsanitary tenement housing where entire families might be confined to a single room with shared kitchens and bathrooms—if indoor plumbing existed at all. Moving into a two-bedroom apartment with private facilities represented a dramatic improvement in quality of life. For immigrant families like the Turovitz, whose oral histories are preserved at the museum, and for African American families who later fought for the right to access these communities, public housing represented both material security and a symbolic inclusion in America’s social contract.

At the turn of the 20th century, faced with public housing units in dire need of renovation and updating, the CHA enacted its “Plan of Transformation”, promising to demolish 18,000 public housing units and replace them with 25,000 rehabbed or newly constructed units over a decade. The demolitions came swiftly, including all but one of the Jane Addams Homes buildings, but rebuilding lagged severely behind. As a 2022 ProPublica investigation revealed, the CHA’s claims of success masked a profound failure of accountability. The agency deceptively counted Section 8 vouchers toward its 25,000-unit goal, and after two decades, thousands of promised replacement units were never built. This effectively scattered predominantly Black public housing residents from valuable central Chicago real estate to often segregated neighborhoods with fewer resources, while developers capitalized on the cleared land for luxury developments.

Today, the public housing social contract continues to face significant challenges. The Trump administration eliminated funding streams for fair housing advocacy organizations and has “stalled at least $60 million in funding largely intended for affordable housing developments nationwide”, according to the Associated Press. At stake is funding for small community development nonprofits that use these grants as seed money for affordable housing projects. The administration has justified these cuts by claiming the organizations were “not in compliance” with Trump’s executive order targeting diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives.

These actions don’t simply represent budgetary adjustments but signal a fundamental shift away from the principle established in the New Deal era: that stable housing is essential infrastructure for both individual dignity and national prosperity.

Nash sees the work of the museum taking on particular urgency in the face of these threats. She is resolute about the museum’s approach in these times. “We will not change who we are…we don’t have to shout from the rooftops,” she said. “There’s wisdom in ‘be gentle as a lamb, wise like a fox.’ So there’s a certain level of just being mindful of the climate that we’re in… It just makes us be more creative.”

Nash’s outlook appears to extend to the institution’s financial planning. While many cultural institutions have seen their federal grants slashed, the NPHM has focused on cultivating diverse revenue streams, particularly from individual donors and foundations who share their commitment to preserving public housing history. By securing multi-year pledges before the current administration took office, the museum created a buffer against immediate funding threats.

NPHM declined to comment on the museum’s strategy with respect to the Trump administration.

Nash hopes visitors will become advocates who understand that housing insecurity could affect anyone. “What’s most important is that we maintain our values… because housing is the basis to everything. If you don’t have secure housing, that affects your employment, then it affects your overall health…if we don’t have that basic human right in terms of housing, it impacts everything,” Nash said.

She believes that when people recognize this universal vulnerability, they’re more likely to speak out to support fairer housing practices, something the museum actively encourages in its mission. As she likes to remind visitors, “The public, the residents themselves, took a stand and said, ‘You’re not going to erase this history’.”

NaBeela Washington is an Alabama-raised poet, editor, and budding art collector. Learn more at nabeelawashington.com