In February, newly elected governor Bruce Rauner proposed his first state budget, which called for massive cuts that would disproportionately impact poor communities, including many black and Latino areas on the South Side. Faced with a $6 billion projected deficit in the upcoming fiscal year, Rauner has called for nearly $4 billion in cuts to social programs, including health and child care programs for low-income people, education and afterschool activities, and mental health services, among others.

Although Rauner is currently negotiating his cuts with Democrats, who hold veto-proof majorities in both state legislatures, in exchange for business-oriented reforms, his office has refused to grant a Freedom of Information Act request from the Associated Press to see the reforms he would propose. (His office also did not respond to questions it received from the Weekly.) Rauner has said he wants to “leverage” the budget to better achieve his priorities; as such, the cuts represent a first look at what those priorities are—as well as how they might be felt once a final budget passes.

Although Rauner has characterized his budget and the cuts within it as “necessary, but difficult” choices, he has allowed the income tax to drop from five percent to 3.75 and the corporate tax to drop from seven percent to 5.25, and he has also lifted a freeze on an additional $100 million in corporate tax breaks (approved but not implemented by Governor Pat Quinn). Most of the income tax savings went to the wealthy, with 54.5% of them going to the top 11.8% of taxpayers, according to the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability. Additionally, a report by the Fiscal Policy Center at Voices for Illinois Children finds that reversing the income tax could raise as much as $5 billion while reversing the corporate tax rate could raise between $330 and $770 million. Together, both moves could almost close the $6 billion deficit.

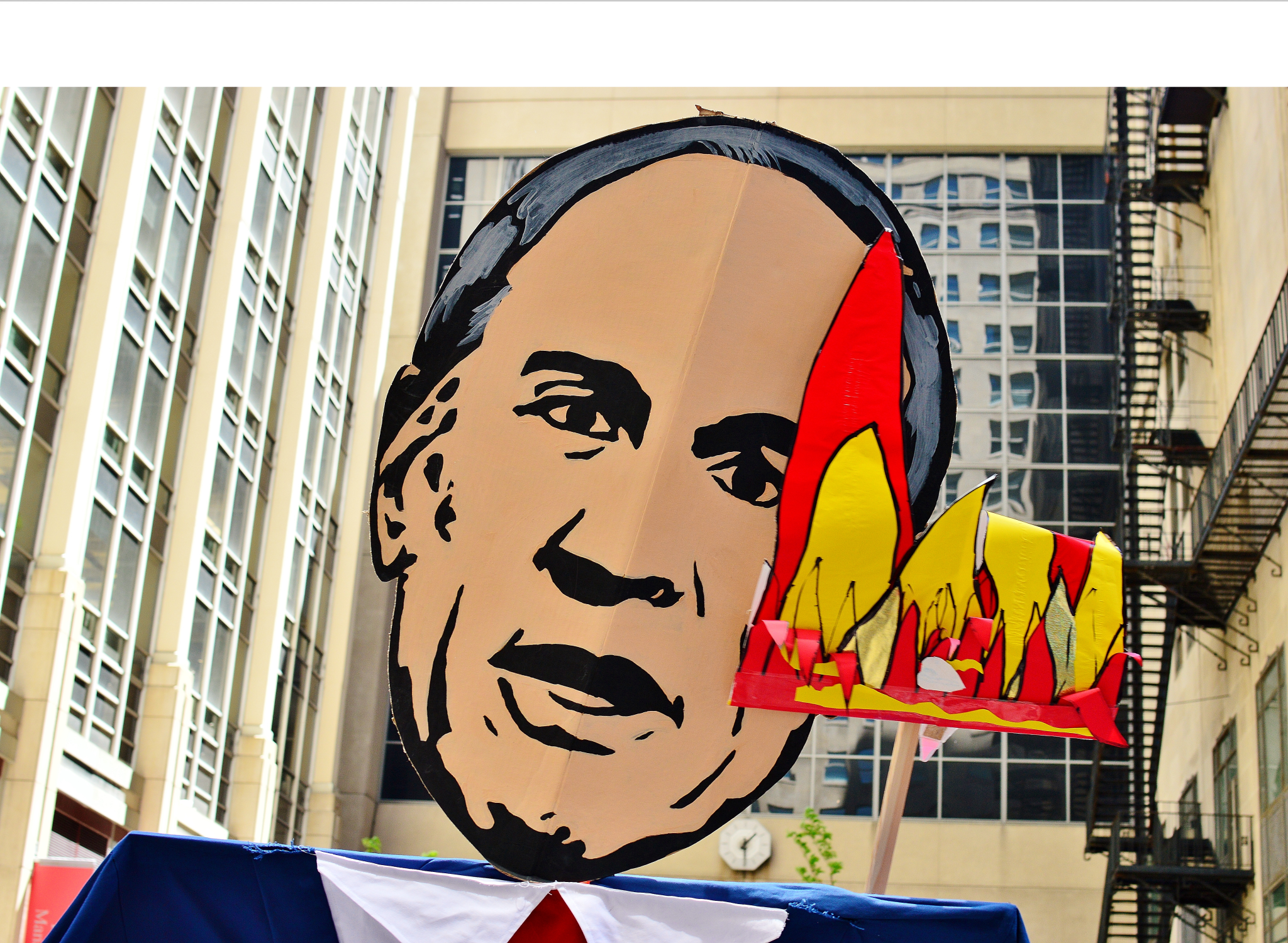

Community organizations have rallied in the face of the budget cuts and challenged both the need for austerity and Rauner’s priorities. Back in March, unions and Fight for 15 brought about 1,500 protestors to the State Capitol and delivered a petition with 10,000 signatories. On May 9, those same groups combined with the Jane Addams Senior Caucus to stage a protest in Winnetka outside one of Rauner’s nine homes. Four days later, they were outside another one of his homes—this time a penthouse in Millennium Park—where they set up a camp they called “Raunerville,” in reference to the Hoovervilles of the Great Depression. And on Monday, fourteen protestors from the alliance Fair Economy Illinois were arrested for sitting in the middle of Jackson Boulevard outside the Chicago Board of Trade (see photos).

The Weekly looked into the budget to assess how the changes might be felt in Chicago and on the South Side.

Health Care

By far the biggest cut is to Medicaid, from which Governor Rauner has taken $1.5 billion. The low-income health care program provides insurance to over half of Illinois children and one of every four Illinois residents overall, and about half the cuts ($735 million) come directly from hospital reimbursements. This represents about thirteen percent of the funds hospitals currently receive to fund Medicaid.

Most hospitals on the South Side are classified as “safety nets,” meaning over fifty percent of the patients they serve are eligible for Medicaid. These include St. Bernard Hospital, Jackson Park Hospital, South Shore Hospital, La Rabida Children’s Hospital, Holy Cross Hospital, Mercy Hospital, Mount Sinai Hospital, St. Anthony Hospital, and Roseland Community Hospital—nine of the state’s twenty-two “safety net” hospitals.

Seventy-two percent of the patients St. Bernard Hospital serves receive Medicaid. The hospital, which is in Englewood, could lose more than $10 million if the Medicaid cuts are implemented, according to Derek Michaels, its director of public relations.

Rauner also plans to save nearly $75 million by conducting an “aggressive review” of those eligible for the program—currently adults in homes making less than 133 percent of the federal poverty line, children in households making less than 300 percent of the poverty line, and seniors and disabled people with incomes at or below the poverty line.

Kidney transplants will no longer be provided to undocumented immigrants, and certain mental health and anti-seizure drugs will no longer be exemptions to the Medicaid restriction of four prescriptions per month.

Services that are not mandatory under the Medicaid program, such as dental care and podiatry, will be reduced or discontinued. Although these services have been cut in the past, they were restored because emergency care wound up costing more.

“People will not miraculously get better if they’re denied care for services,” Representative Greg Harris (D-Chicago) said after the budget address in February. “They’ll just end up at a higher level of care in an acute care setting at the most expensive end of their disease.”

The Department of Public Health will lose around $19 million, mostly in preventative and women’s health programs. Among the programs that will be cut back include breast cancer screenings, AIDS/HIV education and services, the University of Illinois at Chicago’s sickle cell clinic (all $495,000 eliminated), and grants for family planning, immunizations, vision and hearing screenings, and outreach.

Lower-income seniors also face a devastating $140 million cut to the Community Care Program, a waiver under Medicaid that provides home-based care to those who might otherwise need to relocate to nursing homes. Not only does in-home care allow patients to continue living independently in their own homes, it also ultimately saves the government money, in that the alternatives—emergency, hospital, and nursing home care—are all more expensive. The governor also wants to tighten the eligibility requirements for the program, which senior care workers and the IIlinois AARP predict will exclude about 38% of those currently enrolled.

“The people with the lowest need in the Community Care Program are the least likely to ask for help, and the most likely to die due to service disruption,” Amber Smock, Director of Advocacy for Access Living of Metropolitan Chicago, said in an April press release. “Making it harder to get into the Community Care Program will cost Illinois millions of dollars in increased hospitalizations and lost labor.”

For those who remain in the program, the governor also wants to cut the average amount of services by one hour per week.

The budget cuts community mental health programs by 15 percent. This $82 million reduction comes after Chicago closed six public mental health clinics in 2012, four of which were on the South Side. Patients were transferred to privately managed clinics like Thresholds, which took over the building of the clinic in Woodlawn that closed. Now the private clinics would have to cut services under the 2016 budget, too.

“We would be taking so many steps backward with the cuts that are on the table,” Heather O’Donnell, the vice president of public policy and advocacy at Thresholds, told the Tribune in April. “We weren’t a strong sector before and we would be a shell of that.”

Illinois already cut mental health spending by $187 million from 2009 to 2012. Because Medicaid does not pay very high rates for psychiatric services, organizations like Thresholds rely on public grant funds to pay for psychiatrists and serve their low-income patients. As state mental health spending is reduced, so is the number of patients to whom they can afford to give care.

Medicaid also does not cover a number of services for people with mental health issues, such as programs that help them find jobs and stable housing.

As the gap between needed and provided mental health services widens, the government ends up spending more money on mental health care overall—in emergency rooms and jails. From 2009 to 2013, for example, thirty-seven percent more patients in Chicago were released from emergency rooms for psychiatric care, according to an analysis of state records by WBEZ. The largest increase was in 2012, the same year the city closed six mental health clinics.

Education

The budget does add $290 million in spending to K-12 education, but Chicago Public Schools (CPS) expects to lose around $16 million under the state’s funding formula. $10 million will be cut from the Safe Passage program, which watches students who changed schools after the 2013 closings to ensure a safe commute.

Illinois has cut state funds for education for years and will still fall below its own recommended “foundation level” for per-pupil spending. In 2013, Illinois ranked last in the U.S. for the share of funds it committed to P-12 public education (Illinois public schools rely on local property taxes for most of their funding).

A few K-12 education programs will see cuts, including funding for Advanced Placement programs, arts and foreign language instruction, and teacher board certification.

Another big cut will affect universities: the budget proposes a reduction of almost $400 million, which represents thirty-one percent of public universities’ state funding. Each university will receive the same percentage reduction.

While some schools, such as the University of Illinois, have pledged not to increase tuition for the 2015-16 school year, the budget cuts could lead to an increase in tuition rates at other state universities, or to increases in future years. A recent report by Young Invincibles, a youth advocacy organization, notes that the cost of tuition at public universities has increased by fifty-seven percent at public four-year schools and thirty-eight percent at public two-year schools over the last decade, while from 1999 to 2008 state funds for need-based grants fell by twenty-eight percent. The report cites a 2012 task force commissioned by the state’s Monetary Assistance Program, which helps low-income students afford college, that found that “college credential attainment inequities” have already increased because of college affordability issues.

CPS students will have fewer afterschool programs available to them as a result of the cuts. After School Matters, a Chicago nonprofit that offers hands-on, project-based programs, will lose $2.5 million. And Teen REACH, which offers tutoring, college preparation, and cultural enrichment to disadvantaged youth ages six to seventeen across the state, will lose all $3.1 million of its funding. There are eleven Teen REACH providers on the South Side, including the Brighton Park Neighborhood Council and the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization.

Housing and Human Services

A number of programs for homeless people or families at risk of homelessness will see their budgets slashed. The Homeless Youth program, which funds youth shelters and services, will lose $3.1 million, affecting over 1,300 homeless youth. This will impact organizations such as Teen Living Programs, which operates a drop-in center in Washington Park and a transitional living house in Bronzeville, and the Unity Parenting and Counseling Center in Pilsen.

Supportive Housing Services, which provides help to formerly homeless households, will also lose $14.1 million, affecting over 10,300 households. And the Homeless Prevention program, which provides one-time grants to families at risk of losing their homes, would see $1 million cut, which means 955 fewer grants. Overall, homeless programs will lose thirty-six percent of their current funding.

An estimated 45,000 people will be turned away from funded homeless programs this year, according to the affordable housing group Housing Action Illinois.

Many people may not even be able to heat their homes as a result of one budget cut. 155,550 low-income families would no longer receive assistance to pay for heating next year, saving the state $165 million. The state currently puts a surcharge on all utility bills—an average of $1.58 per month, according to ComEd—to fund the utilities of low-income families. The Rauner budget would keep the surcharge but direct all of the money to the state’s general funds instead. 263,000 households would continue to receive heating assistance (the total in 2015 was 418,000), but 22,000 will lose help for emergency heating reconnections (out of 60,000 households receiving it in 2015), and assistance for cooling will be eliminated.

The Department of Children and Family Services would see a cut of $167 million. The programs that would be impacted include early intervention services for children up to three years old with disabilities or developmental delays—cut $23 million, affecting 11,208 children—and foster care transition services for children ages eighteen to twenty-one, which would be eliminated, affecting the 2,400 young adults who currently receive financial assistance when they age out of the foster system without a family or a home.

Criminal Justice

Rauner says he wants to reform the criminal justice system and reduce the prison population by twenty-five percent in the next ten years. But instead of cuts, his budget calls for increases in police and corrections funding. As compared to the budget enacted last year, the Department of State Police will get an additional $8.6 million, the Department of Corrections an additional $17 million, the Prisoner Review Board an additional $1.7 million, and the Department of Juvenile Justice an additional $20 million.

The Department of Corrections will “increase its correctional officer staffing levels by 473 positions in order to improve the safety of our correctional officers as well as inmates.” It will also devote funds to implement a “Risk, Assets, and Needs Assessment (RANA) tool to help correctional facilities identify inmate needs and evaluate their public safety risk,” and devote an “additional $58.5 million to improving the mental health care of inmates.” It plans to save some money, on the other hand, through reduced overtime costs.

In a similar move, the Department of Juvenile Justice will hire more security staff, educators, and mental health specialists. It will also increase funding for Aftercare, a youth-focused parole program, and create an independent ombudsman to investigate complaints and DJJ policies and procedures.

Illinois prisons are overcrowded—the Department of Corrections is at more than 150 percent of its design capacity—and Rauner has called them “unacceptable” and “unsafe.” But reducing incarceration itself is different from improving prison conditions. It is curious that Rauner claims to want the former but is pumping the prison system with more money, and at a time when so many other resources are being cut back.

The one department in the criminal justice system that will see less funding in 2016 is the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, which will have a budget of $102.9 million, just under the $103.3 million it received in 2015. This includes cuts to programs for bullying prevention, violence prevention, and methamphetamine care. The budget for CeaseFire, which employs former gang members to reduce violence in their communities, will also be cut to $1.9 million, from $4.7 million in 2015.

While investing in more basic resources such as schools, healthcare, and housing would be more effective than CeaseFire in reducing violence and improving living conditions, that is not what the people of Illinois and the South Side of Chicago will get from this budget.