With the Obama Presidential Center proposed for Jackson Park, the University of Chicago’s continuing development along 61st Street, and a myriad of other projects large and small, residents are asking: what will Woodlawn become? This is the first article in a series investigating the past, present, and future of the neighborhood.

They came from South Shore, the suburbs, and as far away as Kankakee. Many came from Woodlawn and surrounding neighborhoods: Hyde Park, Washington Park, and Englewood. They even came down from their apartments upstairs. The dozen or so people who filled the community room in a Woodlawn apartment building near 61st and Cottage Grove on a Saturday in early October had come to attend Blacks in Green’s West Fest, a “treasure tour” of the neighborhood.

Naomi Davis, the founder of Blacks in Green (BIG), walked briskly between a greeting table piled with brochures on everything from solar panels to the Chicago art collective AfriCOBRA, and a community room where a dozen or so attendees were waiting for lunch and the day’s keynote speech by sculptor Richard Hunt. Most of the participants, who shuffled brochures and adjusted their reading glasses, didn’t look like they’d taken part in the Fest’s earlier activities, which started at sunrise and included kayaking and fishing in a nearby lagoon.

An email sent to Fest attendees declared they would “Rediscover DuSable, founder of Chicago, as you kayak and fish in the lagoons of Washington Park.” They were told to “imagine corridors of public art in the Obama Presidential District. . . .Take a morning walk along the emerging ‘Michelle and Barack Obama Scenic Drive’. . .an ‘Avenue of Ancestors’. . .inform your self-guided stroll through the gardens of West Woodlawn, 3 great parks, or down to the lake shore where Chicago began with DuSable and where it lives on with black boaters enjoying our Great Lake today.” It was cold and cloudy outside, which is why the luncheon was not taking place in one of Blacks in Green’s adjacent gardens.

Davis said that she imagines Woodlawn becoming a “walkable village,” the type of bustling neighborhood in Queens, New York, where she grew up, and which she says went extinct for most African Americans during her lifetime. “Nowhere on earth do you find the normalization of blight, except in African-American neighborhoods,” Davis said. ”It’s nothing new to see a blighted, Black community reemerge as a new, sexy, shining place to be,” but only when Black people no longer live there. She rejects what she calls the “Help the Negro Industry,” in which outsiders come into Black communities to work on what they perceive as problems. Instead, her work with Blacks in Green—planting community gardens and encouraging more sustainable real estate development, among other projects—embraces the green economy as a way for people to rebuild their own neighborhoods.

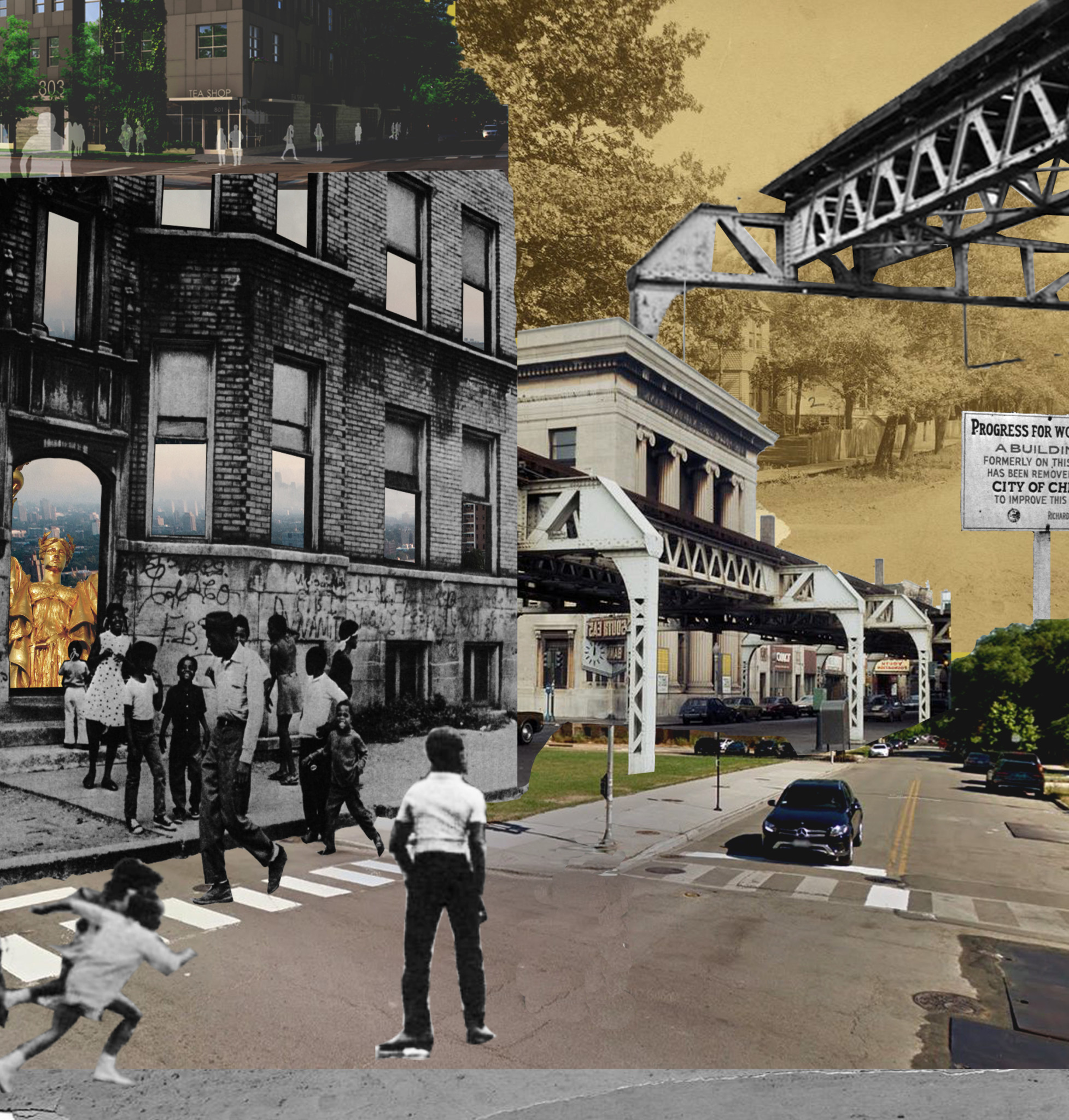

The Fest was named for the western half of the Woodlawn neighborhood. Historically, West Woodlawn’s fabric of two-flats fostered a community of middle-class owners who lived in their buildings and rented out a second floor. The neighborhood was home to Lorraine Hansberry and other luminaries. While Woodlawn’s 63rd Street was once considered “Black Downtown, USA”—its neon lights and crowded sidewalks the subject of painters—racist policies and practices during the 1950s thinned out its main attractions, which include several clothing stores, a public library branch, two schools, a number of single-family homes, and Chicago’s oldest restaurant. The neighborhood’s legendary vibrancy, once on public display, is now tucked away on side streets: the well-tended garden, the block club sign, the friendly greetings of neighbors, and the memories of the elders.

Now, a new chapter for the neighborhood is unfolding. The Obama Presidential Center (OPC), which will be located in Jackson Park, has energized the debate over the neighborhood’s future. The OPC brings the prospect of economic activity that could benefit the neighborhood, but also portends higher property taxes and rising rents that might displace current residents. While some homes display signs welcoming the Center to the neighborhood, park and nature enthusiasts, some of whom live in Hyde Park and other neighboring communities, have taken the City to court to challenge what they say is an illegal use of parkland. Organizers who have shut down roads demanding community benefits like a property tax freeze are sometimes in alliance with the park enthusiasts. Other times, not so much. A Woodlawn resident who has been involved with housing activism for decades said that the tree and squirrel people need to “shut up and sit down.”

West Fest is one group of neighbors’ shot at imagining how Woodlawn’s vibrant past and its present challenges will inform its uncertain future.

Woodlawn is no stranger to radical ideas for urban change. The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park transformed Woodlawn from a swampy Dutch farming village to the destination of twenty-seven million global visitors along with the businesspeople who catered to their needs. In the early twentieth century, a corner of West Woodlawn became the city’s first middle-class African-American neighborhood. East Woodlawn, meanwhile, was home to immigrants from the South and local residents displaced by expressways and public housing construction.

In 1959, a neighborhood coalition invited Saul Alinsky to organize the neighborhood and establish The Woodlawn Organization (TWO), which was led by Bishop Arthur Brazier and Reverend Leon Finney. In its early years, TWO organized a student walkout to protest school conditions and enlisted the help of famous urban activist Jane Jacobs to agitate against abusive landlords. Then, following Alinsky’s radical code, TWO turned its attention to the largest institution in the area: the University of Chicago. Given that the UofC was displacing lower-income Black residents in Hyde Park at the time, Woodlawn residents believed that the university’s plan to expand into their neighborhood was designed to do the same. In 1963, TWO was able to halt the university’s advance at 61st Street in a historic deal brokered by Mayor Richard J. Daley. (At a 2016 community meeting, a representative from the UofC announced that, after feedback from Woodlawn residents, the school would no longer abide by the agreement. This January, the university officially opened its charter school at 63rd and University Avenue.) In 1967, TWO entered uncharted territory when it sought to quell neighborhood violence by using federal funds to provide job training to members of warring street organizations. Saul Alinsky’s legacy of radical organizing would later inspire young Barack Obama when the future president came to Chicago.

In the 1990s, Arthur Brazier and a coalition of neighbors petitioned to tear down the stretch of the Green Line between Cottage Grove and Dorchester that they thought was choking troubled 63rd Street. The rails came down, to be replaced by a handful of suburban-style single-family homes and a series of church parking lots.

Two decades later, Davis’s vision to attract tourists to an ecologically friendly Woodlawn is one attempt to prevent a “nightmare scenario” in which visitors to the Obama Presidential Center campus, which begins where the terminus of the demolished train line once stood, come by car and never set a foot or spend a dollar in the community. Other solutions range from the unlikely prospect of reviving jitney cabs to installing self-driving buses. These are the latest visions in a hundred-year-long history of change.

The most important single development proposed in the Woodlawn area since the 1893 World’s Fair has neighbors, activists, and major institutions on the move. Pastor Byron Brazier, son of the late Bishop Brazier, presides over a congregation of approximately 15,000 members. He also heads up an initiative called 1Woodlawn, which drafts reports to inform the development of the neighborhood and holds quarterly meetings that draw hundreds of residents who come to hear presentations by city officials, developers, and community members, and to voice their questions and concerns. At a 1Woodlawn meeting in August, Brazier told a packed banquet hall in his church, “If we don’t make sure that the community is self-determined, someone else will make the decisions for us.” A resident who represents the 1Woodlawn initiative in her corner of the neighborhood spoke slowly and widened her eyes with excitement when she said, “We can build the first mixed-income community without displacement.”

Bill Eager, vice president of Preservation of Affordable Housing, which erected the building in which West Fest took place, thinks that the vacancy created by the midcentury exodus of over half of Woodlawn’s residents leaves room for both newcomers and current residents. “They say you can’t have it all, but I think they kind of can,” he said.

At the Fest, building residents stopped in the lobby to talk at the greeting table or to glance curiously at the growing lunch buffet. Davis, who wore a black sweater with the green, leaf-shaped logo of her organization, positioned herself at the front of the community room and spoke about her work with the Chicago Department of Forestry and the Morton Arboretum to plant trees along 66th Street leading from Michelle Obama’s babyhood home—just across King Drive at Parkway Gardens, in neighboring Greater Grand Crossing—to the future site of the Presidential Center. This is part of Davis’s vision to create an Obama Presidential District out of Woodlawn, Michelle Obama’s former home, and several other adjacent community areas that would allow nearby neighborhoods to cultivate local tourism initiatives. The concept would address the challenge of linking the OPC to adjacent residential areas—a challenge created in part by the Center’s proposed location in Jackson Park, which is separated from most of Woodlawn by a rail viaduct.

“Sixty-six trees on 66th Street,” she boomed. “Can I get an amen?” The audience obliged. “When we say we are rooting ourselves in place, doggonit, we mean it. Those who bid on the trees,” Davis explained, referring to naming rights, “will receive a sacred certificate with a GPS location, name of your species, name of your ancestor, and signature of the principals at Blacks in Green—that’s me—the Morton Arboretum, and the City of Chicago Department of Forestry. Bidding begins at 250 dollars.” She clarified: “They’re already valued at far more than that.”

Davis smiled at keynote speaker Richard Hunt and asked the audience, “If you saw a boy running around West Woodlawn, would you say that they would be a world-renowned artist?”

“We want to remember, regardless of how Woodlawn looks today,” she continued, “that it doesn’t represent the talents, the commitments of the African-American community here.” Davis thinks those talents might have been more obvious at the time of Black Downtown, USA, “when we were bustling, rich.” That time is chronicled in a large-format book called Tight Little Island, which Davis held up before the crowd. The cover features a painted image of an evening crowd spilling onto the street outside the once-famous Tivoli theatre, now the site of a Family Dollar and parking lot. Davis stood the book up on the table like a tombstone for bygone days.

The large hardcover partly obscured Hunt’s face. Davis told the audience, “You are in the presence of greatness, and no, I’m not talking about me.” There were laughs. “You are great!” someone shouted. After showing off “Made in West Woodlawn” T-shirts, she ceded the floor to Walter Street III, an architect and one of Hunt’s friends. “If you see any young people out there in the vestibule,” Street yelled over to the lobby, “make sure you bring, pull, push them in here as close as possible to a legacy for all of us.”

Hunt remained seated next to a projector flashing images of his work on the wall. “Talk about public art, the Obama Presidential District, and what it means for us to have a place graced by the work of your hands,” Davis prompted him.

Hunt was born in 1935 on the South Side of Chicago; he spent his early childhood in Woodlawn, when the neighborhood was three times as populous as it is now. Beginning in seventh grade, he attended the Junior School at the Art Institute of Chicago on Saturdays and summers. At Englewood High School, he took a mandatory year of art, and then did coursework at the University of Chicago and the University of Illinois before enrolling in the School of the Art Institute in the 1950s for college. Hunt would be the first African-American sculptor to have his work exhibited in a major solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and, in 1968, one of the first artists to be appointed to the National Council on the Arts.

His lengthy career has been defined by public installations. “How do you get a sculpture that heavy hoisted up onto a building?” someone asked about one of Hunt’s larger works that is affixed to a building’s façade.

Hunt described the forty-inch space required for window washers and the dangers of falling ice. Street silently held up a napkin sketch depicting how it was done. “Let’s send that around,” said Hunt. Someone said, “Naomi would sell it!” Davis looked eagerly at the sketch and laughed.“If you think of the Obama Presidential District, coming in from the Dan Ryan Expressway or Lake Shore Drive, some of us have been talking about what it means to be a gateway and corridor into Woodlawn,” Davis said. “We’ve been thinking about where we would want to see a Richard Hunt piece.”

Street said that private development has always been the patron of public art, suggesting that the Presidential Center might commission a sculpture.

“Is there a piece of Richard Hunt art in Woodlawn?” someone asked.

“Not yet.”

“What body do we have to engage?”

“Friends of the Park,” a woman dressed in pink replied. “Friends of the Park,” she repeated. “They don’t want it.”

The subject changed from the siting of a Richard Hunt piece to the controversial siting of the Presidential Center itself. Another woman in a fleece interjected: “They [the Friends of the Park] want it in the community—it belongs here—but they don’t want it in the park.”

Street changed the subject. “As a young kid, what helped you to think about and realize your career?” he asked Hunt.

“Drawing, having the opportunity in the school curriculum to do art,” Hunt responded. “In school I was interested in bioscience, history, but the fact that I got a scholarship to go to the Art Institute and college put me on that path.”

“We came along in a unique time in the United States,” Street added, turning towards the audience. “The public schools gave us access to art, to music. It’s not like that anymore. In the 1960s—that was American apartheid—we still had the opportunity to pursue what we wanted to. Even in those circumstances, there were other Blacks who went ahead.”

“He had the courage,” the woman in pink summarized.

“Well, family,” Street said.

“A support system,” she responded.

Whether it was courage, family, a support system, or the public school curriculum that helped Hunt realize his career, the differences between the present and the past were shaping the day’s discussion more than the artist’s particular story of success. Since Hunt was a child, Chicago’s vast public housing complexes have been constructed and then destroyed. The city’s African-American neighborhoods passed from unprecedented overcrowding to mass vacancy. All the while, prominent figures and unknown neighbors organized over the course of decades to fashion a better Woodlawn according to their liking—with (or without) elevated trains, green space, and large parking lots.

Blacks in Green envisions Woodlawn becoming part of the Obama Presidential District, a designation that Davis says will allow neighborhoods to cultivate local tourism and define a large swath of city anchored by parks, trees, and public art, where BIG can remain vigilant about the impacts that development might bring. Contention over the Presidential Center’s location, the risk of residential displacement, and the vast social, economic, and political differences separating today and the years when Cottage Grove was packed with neon lights—all that might complicate this vision. As Davis put it in a later conversation, “Will the legacy of America’s first African-American president be Black community wealth or Black community displacement?”

“I like the idea of getting from one side to the other—part of Olmsted’s idea was to get people out and around trees,” the woman in the fleece said, still dwelling on the Presidential Center even though the conversation had turned to Hunt’s childhood and the early stages of his art career.

At the back of the room, a group of women kept a rotating vigil, stacking Tupperware and tin-foil pans filled with home-cooked, steaming food on two large tables.

Davis stood to close the talk. “Woodlawn is getting fixing to be the greenest, sweetest place,” she said. Passersby filled the back of the room, eyeing the feast. “We’re going to have some closing words.”

“West Fest 2018 is a fundraiser for us,” Davis continued. “Bring the mugs and shirts back!” Someone in a Blacks in Green sweater jogged the items up to the front of the room. “This isn’t something crass. This is made in West Woodlawn, made in the Obama Presidential District. This is a fifteen dollar mug.”

The crowd around the food tables was antsy as Davis outlined what would happen the rest of the afternoon. A Black woman whom Davis described as “an attorney, a commodore,” would visit from the Jackson Park Yacht Club to talk about boating on Lake Michigan, followed by a late afternoon reading of Gwendolyn Brooks’s writing by her only daughter.

“I’m sorry she isn’t here to see Woodlawn coming back,” Hunt said. Brooks had graduated from Hunt’s same high school. She died in 2000.

“A beautiful community,” the woman in pink reminisced.

Before the crowd could rise for food, a woman bowed her head and recited a prayer to honor the day, the meal, and those in attendance. She offered praise to God, then to Jehovah, then to several other names, and then paused as if to think if she had missed anyone before concluding, “Allah.”

With the prayer concluded, the audience raised their heads. A voice rose above the growing din:

“I think the elders should be served first.”

Max Budovitch is a contributor to the Weekly. He last wrote about Tuley Park for the Weekly’s Best of the South Side issue.

My family has lived on 62nd and Champlain since the 1930’s; we were one of the first black families.I grew up on 62nd and Champlain avenue and graduated from two neighborhood schools, Sexton and Hyde Park. As a small child, I saw the first black person come out of his house with his golf clubs. It was a thriving, wonderful community with structure, and achievements. Our community produced teachers, lawyers, engineers and other black professionals. Unfortunately, the years have not been good to my beloved community. While I returned after college, few others did. We need a Marshall plan; there is no one solution to address years of neglect. Who profits is the question.

Wonderful article that I very much enjoyed. Have you done any research via the “Woodlawn Booster” newspaper publication; now defunct? You would be able to totally consume what was going on in the history of the African-

American Woodlawn community in Chicago during 1959-1967 ect.

Please write more articles on Woodlawn and the people there! I am engrossed; because I lived there too from 1959-1964.

There is a wonderful abstract metal sculpture by Richard Hunt, in nearby South Shore. Specifically on the West side of South Shore Drive just south of 79th Street.

Woodlawn community is GONE.

July 25, 2024, the Woodlawn Neighborhood is still Dead, without a beating Heart & No Soul there is no reviving it, I’m sorry but it is now a dream a memory.