I spent 2016 researching Chicago’s police-in-schools program. I sought to understand the accountability system that allowed a police officer serving in a high school to return to his post only days after fatally shooting an unarmed teenager.

Part of that was understanding the history of the program—I spent hours trying to make sense of when and how the school police unit was introduced into Chicago Public Schools (CPS) through years of City Council minutes and Catalyst Chicago articles from the 1960s. Ultimately, however, the history of police in schools was only a small portion of my story.

The piece, published in the Reader in February, detailed a group of police officers who were outside the eye of their formal employer, the Chicago Police Department (CPD)—which already had a dismal history of punishing misconduct—and instead worked closely within CPS, a system that had eschewed any formal responsibility for overseeing police officers serving in its schools.

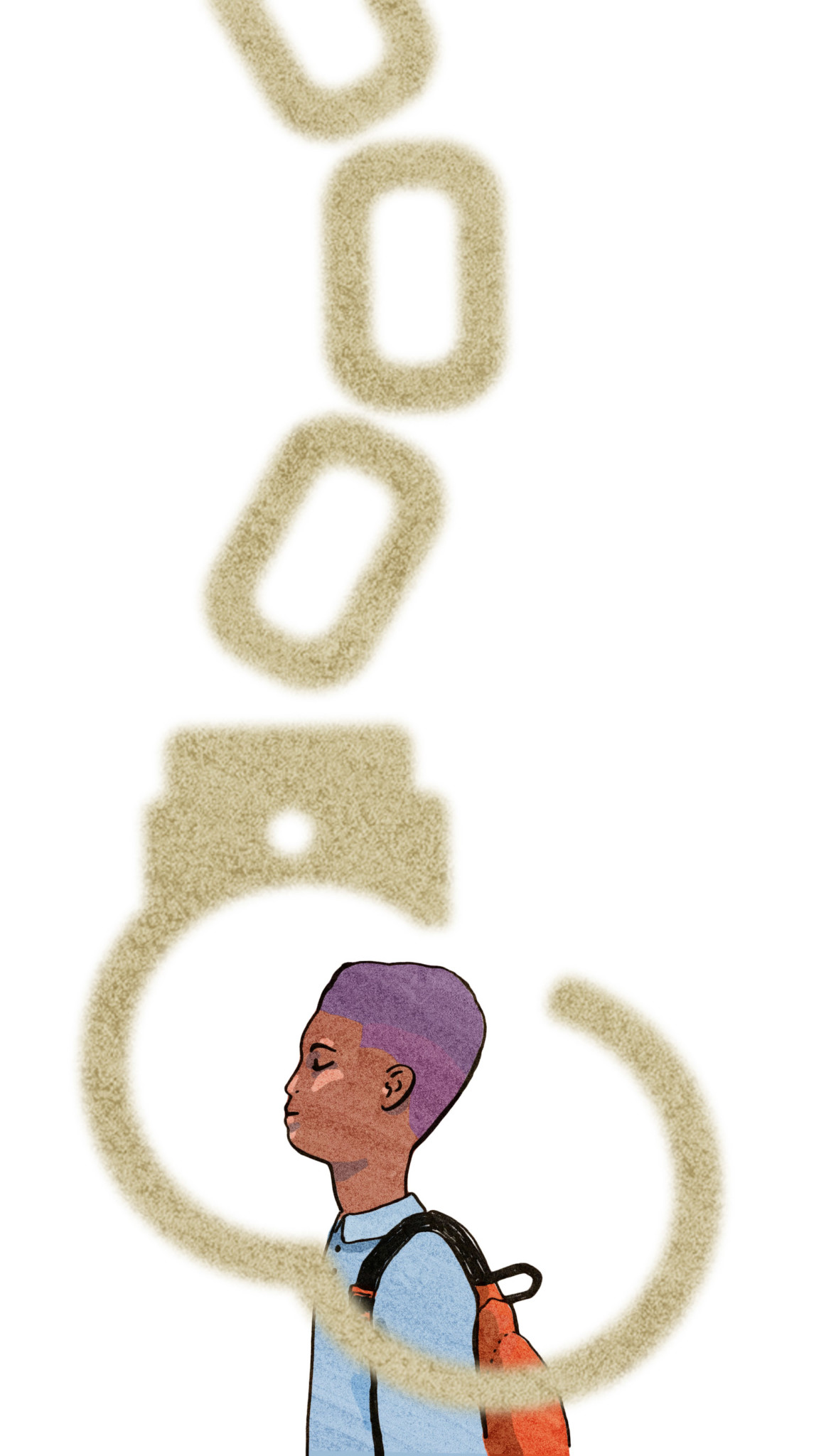

Shortly after, Louis Mercer, then a PhD student at the University of Illinois at Chicago, reached out to me. His dissertation, tentatively titled “Detention of a Different Kind,” traces the origins of the school-to-prison pipeline back to attempts to quash student organizing, as well as a quid pro quo relationship between the police and the city.

Today, the consequences of the school-to-prison pipeline have been well-documented, and the efforts against them are being fought by students, parents, and advocates at many levels. Understanding its origin goes a long way towards informing that battle. I interviewed Mercer about the timeframe leading up to the 1990s, when then-Mayor Richard M. Daley introduced the first formal school police unit.

When did Chicago first bring law enforcement into public schools, and how did that role change over time?

There is one very early example from the Progressive Era—there was a woman named Maire Connolly Owens that might have been the first female police officer in the United States. She worked in conjunction with the Board of Education to retrieve children from workplaces and get them back into schools—a kind of truancy officer hired by the police department. But the presence of police in schools was extremely uncommon in most of the first half of the twentieth century. That changed with the expansion of the Youth Division (first known as the Juvenile Division) of the police, which began under Mayor [Martin] Kennelly in the 1940s. The nearly one hundred officers, many of whom were women, were often assigned to jurisdictions around schools to stop any fights that might occur after school. On occasion, they would operate within schools at the invitation of principals if fights or disturbances were frequent, but it was also a rare occurrence and never a permanent arrangement. The official relationship between Chicago Public Schools and the Chicago Police Department began in 1966, when off-duty police were hired as security guards.

Were there any particular banner years for policing in CPS?

1966 is the year when you can see a formal relationship form between the police and Board of Education. In 1966, the Board of Education of Chicago first hired security guards, all of which were off-duty police officers. The security guard force was only six people that first year because [of] the funding allocation problems, but funding quickly grew until there were about five hundred security guards by 1972, most of which were off-duty police officers, armed and with the right to arrest. Some principals even asked them to wear their uniforms in the schools.

Two factors were particularly potent in the placement of police as security guards in schools. One was a push from the Chicago Teachers Union. From the 1940s to the 1960s, CTU President John Fewkes used instances of violence against teachers to argue for safer working conditions. This was one small aspect of the CTU’s larger effort to gain bargaining power. So unsurprisingly, when the CTU gained recognition as the sole bargaining unit for teachers in 1966, the security guard program materialized.

The other factor is civil rights demands for improved education. Black activists strongly pushed for desegregation of schools in Chicago in the early to mid-1960s, earning national attention with massive boycotts and sustained campaigns against Superintendent Benjamin Willis’s efforts to maintain school segregation. Black and Latino student voices grew stronger in the mid- to late 1960s as well, with students demanding more representation of people of color in the curriculum and staffing of schools.

Those that structured the first districtwide security force saw this rising activism as a threat. For example, the first director of the security department of the Board of Education, Edward “Don” Brady, was a white former principal at a South Side school. In 1965 he was assaulted by a group of students. In a Chicago Tribune article about the incident, Brady argued that the students should not face severe punishment, but he also is quoted as saying, “These assaults…are at least partially due to the unwarranted attacks on Dr. Willis, and these children hearing about unlawful sitdowns in the Board of Education building. Certain adults must quit influencing these children to break the law.”

The very next year, he became the first director of security that oversaw the off-duty police security guards. His mentality, and that of administrators at the Board of Education and in schools, were very concerned with Black and Latino student voices growing stronger. The presence of police was clearly meant to tamp that down.

Did police involvement in student protest go beyond admonishment and policing for violence?

Yes—many students of color that led protests and walkouts in their schools were arrested for their actions. Interestingly, and disturbingly, student protest leaders were also being surveilled by police in the late 1960s. Due to the legal restrictions on publishing information from the Red Squad Files [documents from a covert police unit that targeted leftist and civil rights groups in the 1960s], I can’t give specifics on names or schools, but most of what I’ve seen were principals reporting a student protest leader to the police. Many case files describe a principal labeling a student an agitator, and the Red Squad creating a file for this student. But there are also instances where an informant would attend meetings and report to the Red Squad about an active student leader’s group.

How did police in schools expand in Chicago from the 1970s to today?

In the 1970s and 1980s, most of what fueled demands for off-duty police as security in schools were fears over changing demographics in schools, drugs, and gangs. Particularly on the West and South Sides, many schools quickly flipped from majority white to majority black, but during the change, racial violence often broke out, resulting in both black and white parents demanding the presence of police to maintain order.

Black parents framed their demands for police presence very differently from white parents. Black parents and groups like Operation PUSH saw police as a source of protection for black students moving into majority white schools—think Ruby Bridges or the Little Rock Nine being protected by federal troops while integrating their schools. But they simultaneously asked that the police provide arrest records from within the schools to guard against racial bias. White parents frequently used colorblind language to describe their desire for police, claiming that the presence of students from other neighborhoods—read: Black—posed a physical threat to the students that had previously attended the school—read: white.

In the 1980s, gangs became the main impetus for keeping police security guards in schools. The murder of Simeon [High School] basketball star Ben Wilson in 1984 renewed a citywide focus on gang prevention, and this influenced the continued presence of security in schools.

In 1991, Richard M. Daley used his tough-on-crime stance and instances of shootings involving youth around schools to require the presence of two uniformed police officers in each high school. The next year, seven-year-old Dantrell Davis was caught in the crossfire of a gang shooting in Cabrini-Green as he walked to school with his mother. Even though it happened outside of school, Daley used the press focus on gang violence to call for all schools to place metal detectors at their entrances. Surveillance technology has since grown to include cameras that send their feed directly to police precincts and the development of police sub-stations at some high schools that allow for [the direct] booking of students arrested in the school.

Recently, after the school district missed millions of dollars in payments to the Chicago Police Department for officers in schools, Mayor Emanuel agreed to bail out the district and have the city pay the tab. If we follow this money trail—the off-duty police padding their incomes with more hours as security guards, the police department paid directly by the district and now the city—it becomes clear that a major factor in the placement of police in schools is the steady funding stream it gives the CPD. These officers who are not trained to work with youth in any way are nonetheless given these assignments. At the same time, parents and teachers do have legitimate security concerns, but it seems the only financially supported resource available is more security. Of course, this financial relationship between the CPD and CPS works out until budgets get strained. Principals right now are having a hard time trying to find the budget for their own guards at the schools, but thanks to Rahm, the money is still there for police.

It is important to note this is a very different scheme from big cities like L.A. and New York that have their own police forces for schools. Their school resource officers are specifically trained to work with youth. That’s not to say the presence of any kind of police in schools is not problematic, but if a district feels it must place officers in schools, it seems they should be trained to be there. In Chicago, the relationship between police and schools seems to be a financial relationship rather than an actual plan to try and make schools safer.

This continued presence of police is problematic in many ways. At the beginning of this school year, Mayor Emanuel told the undocumented students at Eric Solorio Academy High School in Gage Park “you have nothing to worry about” and that they will always be welcome in Chicago. However, with DACA [the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals immigration policy] set to expire and the Trump administration threatening to coerce police to enforce federal immigration law, the presence of police in schools is a real threat to those students and their families.

Race is central to this problem. While about fifty percent of CPS teachers are white, over ninety percent of CPS students are not white. Ample studies show that white teachers remove students of color from classrooms more often than their white student peers. Over-policing and surveillance constantly give teachers the option to use police as a discipline tool. The threat of arrest becomes a way to tamp down violence in schools, but the long-term effect of this is the continued criminalization of youth of color and schools that resemble the carceral system.

Yana Kunichoff is an independent journalist and documentary producer who covers immigration, policing, education and social movements. She has worked for Scrappers Film Group and City Bureau, where she won a Sidney Hillman award. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, The Atlantic, Pacific Standard, and Chicago magazine, among others. Follow her work at yanakunichoff.com or on Twitter at @Yanazure.

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly

When I was a student at Austin we had police assigned there after a black/white riot that occurred October 8,1965. Officer Harris was permanently assigned there and unfortunately was killed a number of years later outside the school. So that predates your assertion.

Susan, I would love to speak with you about your experiences at Austin High School in the mid-1960s! Indeed, you are right, police were sometimes assigned to schools (mostly ones going through tumultuous racial change) prior to 1966 – it’s just that the off-duty police guards weren’t funded by the Board of Education until that year. If you are interested in sharing your stories with me, I would love to include them in my research – email me at lmerce3 at uic dot edu – Thanks for your comment!

Schools give up their own agency in resolving situations, which are often nuanced, when CPD is involved. Schools should be able to develop their own due process and solutions in these situations to avoid dangerous escalation at all costs.