Murmurs and greetings circulated through the wood-paneled meeting room of Bryn Mawr Community Church as one hundred South Shore residents settled in for the monthly 5th Ward meeting on May 23.

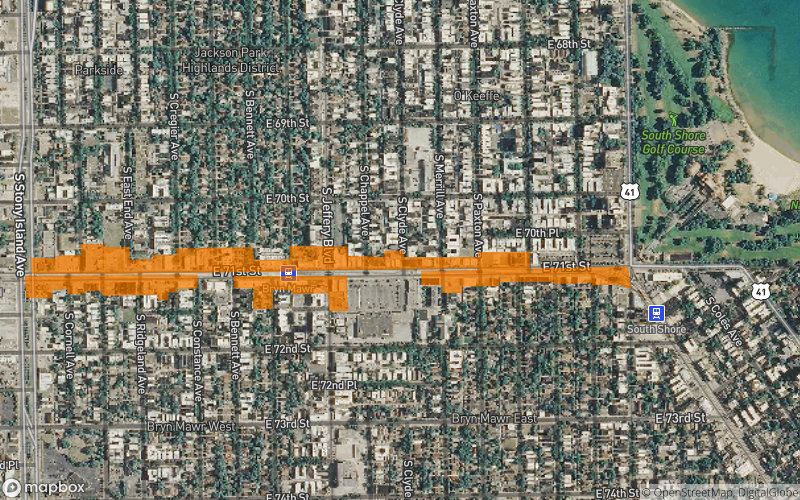

On the evening’s agenda was the first public discussion of a set of ordinances that Alderman Leslie Hairston of the 5th Ward had quietly introduced into City Council two months prior. These ordinances would rezone a mile-long stretch of 71st Street in South Shore, between Stony Island and Yates Avenues, from a mixed-use commercial district to an entirely residential district.

Most buildings along that stretch of 71st house street-level storefronts—many of them vacant—with apartments on top. Should the proposal to change the street’s zoning to residential be approved, prospective business owners would no longer be able to open up in those storefronts by right. Instead, they would need either to seek the approval of the alderman, who could submit a rezoning ordinance on their behalf, which would then be subject to approval by first the zoning committee and then the full City Council, or to file for a zoning variance—a process that entails paying a $1,025 nonrefundable fee, oftentimes hiring a lawyer, and waiting for up to three months to hear the outcome of the request.

Hairston presented the zoning change as a means of reinvigorating the corridor by stopping “undesirable” businesses from opening up in the area. Previously, she had identified these as convenience stores, dollar stores, and beauty shops. At the meeting, she expanded that category to include salons and barbershops.

“Ever since I got in office, you have consistently voiced your frustration about the lack of diversity in the businesses on 71st Street,” Hairston said from the front of the room. “No more hair salons, nail salons, barbershops, dollar stores, and convenience stores that sell single cigarettes, white T-shirts, and harbor criminal activity. We need to turn our business corridor around.”

Although Hairston’s promise to “turn around” the corridor was met with cheers and applause, the details of her plan to do so were met with concern from attendees, who questioned whether she should have the power to determine what businesses populate the street.

“As a constituent, it’s a bad idea,” South Shore resident and activist William Calloway stood up midway through the meeting to interject, “’cause what if she doesn’t like the business trying to come in, and then she got the right to say no?”

Hairston is not the only South Side alderman recently to point a finger at salons clustered in a struggling commercial corridor.

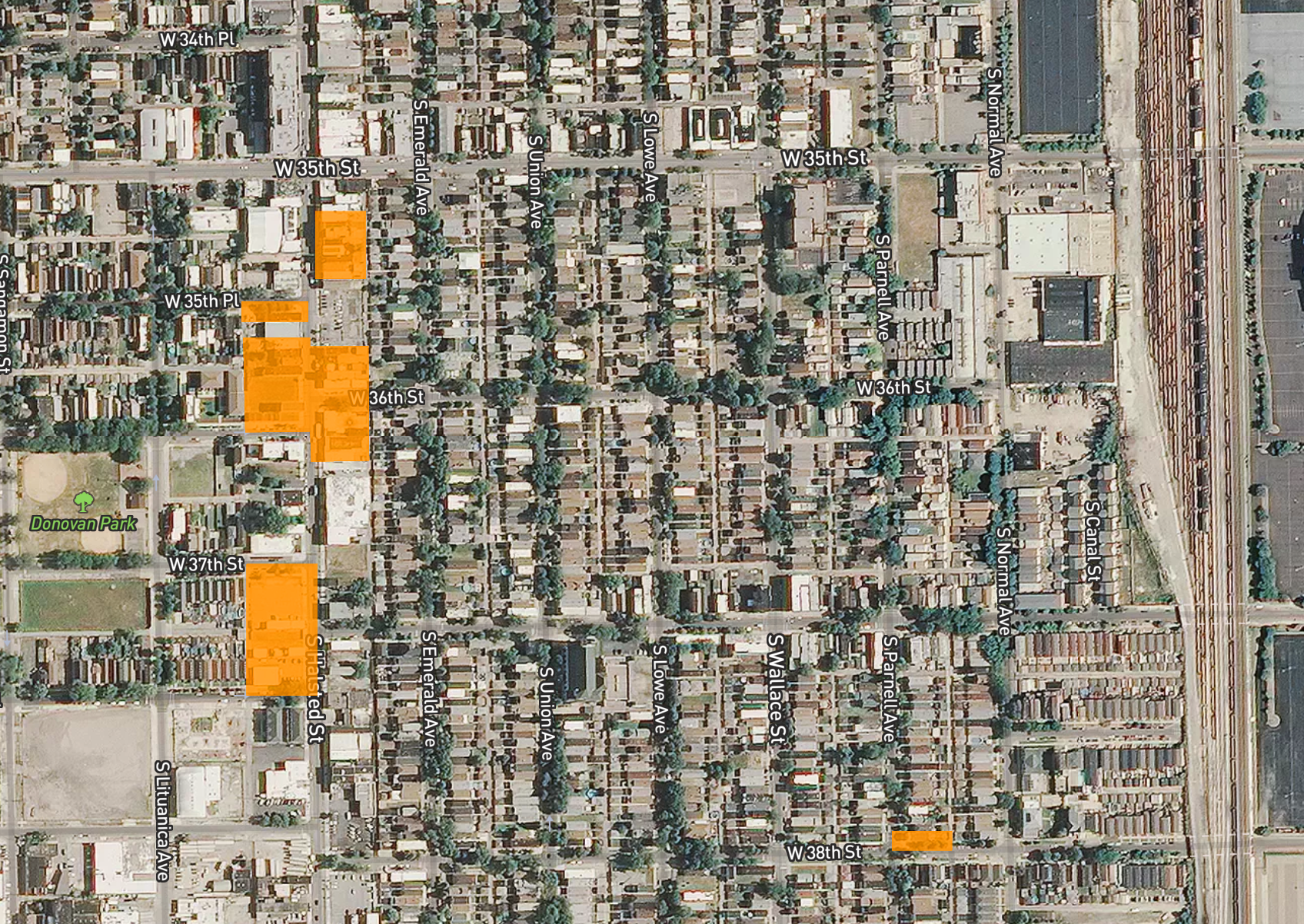

The day after the 5th Ward meeting, Alderman Patrick Daley Thompson of the 11th Ward introduced a set of ordinances to downzone commercial and industrial parcels along Halsted Street between 35th and 37th Streets (as well as a stray property on 38th and Parnell) to residential. When DNAinfo followed up with him about the downzoning ordinance two weeks after the fact, Thompson justified the zoning change as a means of preventing certain businesses—nail salons, hair salons, and massage parlors—from opening in the future.

The use of downzoning to target “undesirable” businesses is nothing new within the Chicago political arena, though in previous decades, bars and “adult” businesses had been the object of aldermanic objections, not beauty salons.

Hairston and Thompson’s insistence that targeting salons (alongside other “undesirable” businesses) is key to solving the deep-seated problems of vacancy that both corridors have faced—and criminal activity, in the case of 71st Street—have left many skeptical that the aldermen are acting in the interests of the larger community. This is especially true in South Shore, where new development, including the Obama Presidential Center and Tiger Woods-designed golf course, is expected to change the face of the neighborhood.

The rezoning ordinances have come to different ends. Thompson’s ordinances, though likely to pass, have yet to go to a vote in the City Council’s Committee on Zoning, Landmarks, and Building Standards. Hairston, however, has withdrawn her rezoning ordinances, announcing at the most recent 5th Ward meeting on June 27 that she will be soliciting advice from the architecture and urban planning giant Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and has since denied targeting any specific type of business.

Nonetheless, the resulting conversations in Bridgeport and South Shore have pulled at the fabric of rhetoric that suggests salons are incompatible with successful corridors or not desired by the larger neighborhoods. And in South Shore, these conversations have illuminated an alternative, community-driven way forward.

When Alberto Murillo, the owner of Antonia’s Beauty Salon (3525 S. Halsted) thinks of the Halsted Street of his childhood, he remembers “a completely different Halsted on that side than there is now.”

Across the street from Antonia’s stands the old Ramova Theater. Weeds sprout from the theater’s terra-cotta edifice, and below, vacant storefronts fan out in either direction. A relic of a bygone era in Bridgeport and in some regard the greater South Side, the Ramova shut down in 1986—about a decade after the Murillo family began cutting and styling the hair of Bridgeport residents.

According to Murillo, the dynamic on Halsted is much the same today as it was twenty years ago, when he was growing up and the theater was already long closed—little foot traffic and little pull to the area south of 35th Street. Nonetheless, it was a little less empty: there was a bakery across the street and, until very recently, the Ramova Grill (which closed in 2012 and stood next door to the theater) and Carlos’ Alterations Shop (which recently relocated to 31st and Shields).

“We’re kind of just at the fringe that’s always been there,” Murillo told me. “So people find their way to it.”

Now what remains in the vicinity—among industrial shops, a tucked-away bar, a yacht sales store, and ward committeeman John Daley’s insurance brokerage—are salons. Immediately to the north of Antonia’s light blue awning are Nail Station, Salon Olori, and Hao Spa, a massage parlor. Along 35th, there are three more salons—Chicago Curl Collective, Anna’s Beauty Salon, and a Paul Mitchell studio—and further north up Halsted, Bliss Nails.

This cluster contains a mix of longstanding community institutions and more recent entries. Antonia’s, Anna’s, and the Nail Station have been open upwards of ten years, while Salon Olori, Hao Spa, and Bliss Nails opened less than two years ago.

“Honestly, you can get a haircut with us, at Salon Olori, at Anna’s, and we all pretty much offer the same service,” Murillo said, “but I think what really threw us apart was my mom’s personality; she was really welcoming.”

Murillo’s managers and clientele are mostly local, and most have been coming in since they were children. Dee Desalu of Salon Olori, one of the newer Halsted salons, however, pulls in customers from other neighborhoods through social media. Her shop has dark glossy windows and an inset door with a buzzer. On a Saturday afternoon, there is no one visible in the cavernous room behind the two sets of doors.

Desalu says that because she is not tied to the neighborhood by her customer base, she may leave for the West Loop once her lease expires in two years.

While perplexed by the clustering of salons, Desalu doesn’t think it’s a problem for business. The salons have different specialties and cater to different demographics, besides: of the two hair salons on 35th, Chicago Curl Collective serves a primarily Black customer base, according to Desalu, while the Paul Mitchell salon serves more Hispanic and white customers. “Anna’s and Antonia’s have been around for quite some time and they’re right around the corner from each other,” Desalu said. “And I’ve been here two years and I don’t think any of the business has stopped my business from being successful. To each his own.”

Thompson claimed that the community is opposed to the salons that have recently opened up.

“More and more, a lot of these storefronts were being leased to nail salons and massage parlors, all permitted uses under B [mixed-use commercial] zoning districts,” he said. “And then we would immediately hear from the community that that was not the type of entertainment they were looking for—they were looking for restaurants.”

Only one massage parlor has opened up recently, however: Hao Spa opened earlier this year. The windows are partially concealed with curtains and posters, and customers must be buzzed in. I was allowed entrance, but the proprietor did not wish to speak on the record.

And the only recently opened nail salon on Halsted is Bliss Nails (3214 S. Halsted). But Bliss opened two years ago, and on the site of a former nail salon. When I came in on a Saturday morning, every chair was full. An employee who did not wish to speak on the record said that Bliss had been well received by the community upon opening.

It may be that there is greater legitimate discontent with massage parlors, long viewed unfavorably in Chicago. The owner of a store on Halsted, who asked not to be named, said he supported the ordinance because he believed it would block new massage parlors from coming in—and relayed rumors he’d heard recently that parlors were looking to lease empty storefronts on Halsted, though they had been stopped. (Hao Spa received a business license in April of this year, and, according to the alderman, more massage parlors have tried to open recently in storefronts for lease.) Unlike hair and nail salons, which under a provision in the Chicago zoning code must apply for a special use application if opening within 1,000 feet of another similar business, massage parlors may open by right in a commercial district.

What lies beyond this thousand-foot range are the 3600–3700 blocks of South Halsted, zoned mostly industrial and commercial. The proposed zoning changes here look like patchwork: included in the new residential district on the east side of the street is a restaurant equipment manufacturer, but not the two auto shops owned by Dominic Bertucci, a meat wholesaler, or the 11th Ward Regular Democratic Organization. On the west side of the street, the old Schaller’s Pump and adjoining properties, owned by the Schaller family, have been downzoned to RS-3, as have four parcels to the south owned by the Kaminski family. It seems unlikely that salons would even consider opening here, given the more industrial nature of the buildings and the even sparser foot traffic these blocks receive.

Some longstanding salon owners do not see the issues the corridor is facing as related to the question of salon and parlor density.

When I asked Anna Pervin, who runs Anna’s Beauty Salon at 755 W. 35th, right around the corner from the area affected by the ordinances, why Thompson was doubling down on nail salons and parlors in the area, Pervin passed on diplomatic language—“I’m not scared of anybody,” she said, deadpan. While she was unsure why the alderman was focusing on salons, it didn’t surprise her. “[Thompson] doesn’t associate with the little people,” she said, “like we are.”

Pervin, who has run her hair-nails-and-makeup salon for thirty-one years, said that she recently began to consider leaving the neighborhood. After a spike in business robberies—at the Family Dollar, the Bridgeport Bakery, a family-run convenience shop, and a MetroPCS—within the last six months, Pervin says neither she nor her customers feel at ease.

Not all agree that this should spur alarm. Murillo said that while he is aware of the recent robberies, he is not concerned about it affecting business and has in fact recently extended business hours from 6pm to 8pm for the benefit of customers with longer working hours.

Others simply point out that this stretch of Halsted has been headed in this direction since the Ramova closed.

Amy Lee has run the Nail Station at 3519 S. Halsted for twelve years. Like the Murillos, Lee owns the building that houses her business. She said she was not worried about the ordinance because of her loyal customer base, and because she wasn’t planning on moving or leasing out her storefront.

“You see, the area is dead,” Lee told me, gesturing through the salon’s busy window toward the empty sidewalk. The empty Ramova loomed across the street. Her customers, many of them long-time Bridgeporters, will occasionally reminisce in the salon chair about date nights, Lee said, when film tickets cost just a quarter and the corridor was more alive.

Thirty-five blocks south and across the Dan Ryan, salon owners had a more mixed reaction to the alderman’s language about salons. There are many salons on the 71st St. commercial corridor—by the Weekly’s count, five nail salons, eight hair salons, and four barbershops—but they are spread out along the street.

The corridor stretches alongside the Metra tracks from Stony Island to the South Shore Cultural Center. Most of the businesses are convenience shops, community centers and offices, salons, and restaurants, but traces of an older 71st Street, constructed around and for entertainment, remain.

Although the Hamilton Theater was demolished in 2002 after having been shuttered many years, the Jeffrey Theater, built in 1923, was remodeled in the nineties for use as the headquarters of ShoreBank. It lacks many of its original features today, but may be redeveloped as a theater by resident and business owner Alisa Starks.

Brianna Jefferson runs Oh Behave Nail Salon at 1863 E. 71st, between Euclid and Bennett. She opened at that location two years ago, and says that business has been “pretty good” since then. But she doesn’t understand why the alderman is targeting salons like hers, among other businesses, in discussions about downzoning.

“I mean the thing is that 71st Street does have a lot of salons,” Jefferson said, “but nail salons and hair salons are not the same—they’re two totally different things.”

One of the concerns that has been aired in the discussion about zoning on 71st Street is about loitering—an activity that many associate with criminal activity. “Do Not Loiter” signs can be found on most building corners. A recent petition circulated on Change.org demands that the businesses in the development on 71st and Jeffrey enforce a no-loitering rule.

On the petition, the offending businesses include Walgreens, MetroPCS, Liberty Tax, Jeffrey Nails, Check Cashers, and a nameless convenience phone store—just one of them a salon. As of press time, the petition had garnered 796 signatures, out of a goal of 1,000.

A public records request filed by the Weekly returned eighty complaints to 311 about businesses on 71st Street between 2014 and 2017. Two of them made earlier in the year were against Oh Behave, alleging that they had no business license. This allegation proved to be false, according to the city’s data portal. Many of the complaints, however, were made about restaurants, convenience stores, and grocery markets.

Oh Behave Nail Salon has never had a problem with loitering, Jefferson said, pointing out that, in her experience, the problem is more or less limited to convenience stores. And, in her opinion, the alderman has done nothing to address the matters of public safety in the business corridor.

“To be honest, I don’t even know who our alderman is,” Jefferson said. “She ain’t doing nothing.”

Although most other hair and nail salons did not wish to discuss the downzoning on the record, those who were willing to talk were less critical of the ordinance. Guyse Dawson, who has run Guyse’s Salon of Beauty at 2309 E. 71st Street for eighteen years, said that while she was initially concerned about the ordinance, when she learned about the alderman’s intention of increasing business diversity along the corridor, she decided it was a good move. It’ll be good not to have “salon after salon after salon,” she said.

At the 5th Ward meeting a block north of 71st Street in May, however, few spoke about salons. The conversation revolved around the interconnected questions of public safety and absentee landlordism: if the landlord packs up and goes home to another community at the end of the day—or never even enters the neighborhood—what incentive is there to work with residents and businesses to ensure the safety and satisfaction of passersby and shoppers?

Those who voiced skepticism about the alderman’s proposal suggested that there might be other ways of achieving the shared end goal of “turning 71st Street around,” which might incentivize communication and cooperation between residents, business owners, and property owners, rather than giving the alderman more of a say in what businesses can open and which cannot.

Chief among the skeptics is Val Free. Executive Director of the Planning Coalition, a group that works to strengthen the links and channels of communication between existing community organizations, she has spearheaded the movement to reestablish the community area councils and block clubs that laid the foundation for South Shore activism in the eighties. Her organizing efforts, which the Weekly covered in an article last year about the Southeast Side Block Club Alliance, have become increasingly visible as members of the community rally in opposition to the zoning.

Soft-spoken and measured, Free maintained in a conversation prior to the ward meeting that while she was sympathetic to the alderman’s efforts, she was unconvinced by the nature of the proposal. “I believe what [Hairston] says about [71st Street] is accurate,” she said, “but I believe there are other ways to do that that are more democratic.”

Free continued to push toward that alternative at the ward meeting. She introduced the Austin Good Business Initiative, an initiative designed by the Austin Chamber of Commerce to tackle vacancy and store-side criminal activity, as well as to reward the businesses that offer quality services and serve as community spaces—an initiative that another attendee, who had previously lived in Austin, endorsed enthusiastically. The initiative was designed to be replicated in neighborhoods that face similar issues.

The alderman said she had not heard of it. When Free offered to send her office the information, Hairston responded, “You can send me, but then again I’ve lived here for forty-five years. I know what the issues are…and with the exception of you, business owners, and landlords, most of you choose not to engage and choose not to participate. That’s their choice.”

The alderman hammered this point home, but it seemed clear that community engagement was not missing. Free’s Planning Coalition, alongside independent activists and other community groups such as Reclaiming South Shore for All, have worked to inform and engage residents on online platforms and in physical venues over the last several months, in order to come up with a more democratic framework for a plan for 71st Street’s revitalization.

But at the meeting this contingent came up hard against Hairston, who equated opposition to downzoning with complacency. Midway through the meeting, a resident asked for confirmation that she would not move forward with zoning should the community’s consensus ultimately be negative. (Hairston notably elected to use “consensus” over “vote,” though she did not elaborate on how the process would work.) But in response, Hairston retorted, “And so you’re saying—I just want to be clear—that you like 71st Street the way it is?”

As the meeting heated up, Alisa Starks, who announced plans to open up a theater location at the old Jeffrey Theater building at 71st and Jeffrey in 2015, stood up in support of the downzoning. “I am for downzoning for one simple reason,” she said. “A $12 million investment means that I want other businesses to come … [but] I don’t want another nail salon opening up next to me.”

No one challenged this reasoning at the meeting. Hairston later said in an interview with the Weekly that it was “not exactly correct” that she was targeting salons or any other specific business type, and that she was responding to what the “community has said they need and don’t need.”

But William Calloway offered a different explanation for the anti-salon rhetoric given voice to at the May 5th Ward meeting: “I think it’s a certain demographic in the community that [Hairston’s] trying to cater to, what they want the landscape to look like…It’s very legitimate to have [salons] in the community.”

Calloway, whose organization, Christianaire, advocates for police reform and is working to develop initiatives to fight neighborhood gang violence, thinks the problems lay deeper than in the presence of salons and dollar stores. “How can you attract businesses until you fix the social issues? I think that’s kind of oxymoronic,” he said.

“She’s not taking a proactive approach to a lot of these social ills,” he said. “If you’ve got drug addicts then you should say, ‘My community has a substance problem.’ If you’ve got people in debt then you should say, ‘My community has an economic problem, and I need to work to try to fix that.’”

Alderman Hairston has since withdrawn the rezoning ordinances and is soliciting advice from an urban planning team, and in a later interview with the Weekly emphasized that going forward there will be an advisory council that “will be meeting regularly” with the Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill planning group.

At the head of the advisory zoning committee will be Susan Campbell, Cook County’s director of planning and development and a resident of the Jackson Park Highlands Disrict in South Shore. An early supporter of the proposed rezoning, Campbell was unable to provide an example of successful residential rezoning in a commercial corridor comparable to 71st Street while speaking up for the ordinances at the May ward meeting—other than Garfield Boulevard, which, as one community group pointed out, remains largely vacant aside from the development resulting from the University of Chicago’s collaborations with Theaster Gates.

While residential zoning may no longer be in the immediate future for 71st Street, questions about the changes the two corridors will undergo and who gets to participate in their creation remain on the table for both communities.

As the South Shore neighborhood gears up for the incoming Obama Center and professional-level golf course, there is worry that any changes undertaken might result in a more aestheticized version of the corridor, one which appeals to those who have a lot invested in its prosperity, but does not address these more deep-seated problems that Calloway brings up.

And while residents have pushed for a more community-driven process for implementing better business practices, Hairston has said that a rezoning of 71st is not entirely off the table and that the programs she implements will depend upon the findings of the planning committee.

In Bridgeport, there is a possibility that the residential downzoning might lead to unexpected results—like an increase in the single-family detached houses allowed by right under the new proposed zoning classification. Although Thompson has denied having any intention of transforming the commercial district into a residential one, anyone would be able to construct a single-family home on vacant land, which is not lacking on Halsted.

“New residential property could bring in more property taxes and more upscale customers for existing and new businesses,” University of Illinois at Chicago political science professor and former alderman Dick Simpson pointed out. He said that while zoning could be used to promote business, this usually occurs within manufacturing and commercial categories, not residential.

It is difficult to predict the long-term impact of zoning changes. But if anyone knows the ins, outs, and question marks of aldermanic zoning authority, it’s Bridgeporters.

Halsted has been an area of focus for zoning changes for decades. “There are areas in my ward that are overrun with taverns, where neighbors just don’t like them anymore,” 11th Ward Alderman Patrick Huels said to the Tribune in 1987 while defending his rampant rezoning practices. By the Tribune’s count, Huels sponsored twenty-nine zoning changes in a three-year period. “I don’t need package liquor stores and fifteen resale shops on Halsted Street,” he said, using language that rings familiar.

A decade later, Huels passed a controversial ordinance downzoning parts of 47th Street and Western Avenue in Brighton Park, industrial-commercial districts, to residential. He let it sit in City Council for three years before bringing it to a vote without the neighborhood’s notice.

Two decades later, aldermen are showing renewed interest in similar tactics.

Alderman Gregory Mitchell of the 7th Ward filed an ordinance recently that would grant aldermen city-wide the ability to unilaterally reject business applications. Hairston, one of the ordinance’s seventeen supporters, has said that if it passes, she would retract her own zoning ordinances. Mitchell’s ordinance is unlikely to pass, however, said Beth Kregor, director of the UofC Institute for Justice’s Clinic on Entrepreneurship, but its implications are concerning: in her opinion, the ordinance would likely discourage entrepreneurs and open the door for corruption.

Even on its own, aldermanic zoning authority, although it has been regulated since the twentieth century, provides an abundant toolbox for those who aren’t shy about achieving their desired ends or fighting their personal battles through political intimidation.

As government accountability nonprofit Project Six reported earlier this year, Alderman Joe Moreno of the 1st Ward threatened to downzone the property that until recently housed music venue Double Door in order to punish the property owner, Brian Strauss, for evicting the long-running business. In a recorded conversation, Moreno promised that after the targeted downzoning (also known as “spot zoning”), Strauss would not see another tenant for three years and that he should expect “inspectors in here on a daily basis, you watch.” Alderman Daniel Solis of the 25th Ward and Alderman Carlos Ramirez-Rosa of the 35th Ward have also recently used spot zoning to discourage development in rapidly gentrifying parts of eastern Pilsen and Logan Square.

Corruption in the zoning process might take a more insidious shape. In a commercial corridor rezoned to be residential—where businesses cannot open by right—a prospective business owner might be encouraged, explicitly or implicitly, to make a campaign contribution to the alderman before asking for a zoning change.

Even if aldermen proclaim democratic intent, as Thompson and Hairston, and develop a robust community-input process for rezoning matters, it will result in discrimination and should be ended, Kregor wrote in a Sun-Times opinion piece.

“No single alderman—or community group—should exercise control over entrepreneurship in a neighborhood. No alderman or community group can forecast which business will be a ‘problem business’ or a ‘desirable business.’ If the power to approve or reject a business is discretionary, it will be discriminatory,” Kregor wrote. “Even people with the best intentions will be operating on assumptions and biases. They may assume, for example, that all dollar stores or nail salons are the same and no more are needed. They may also assume that local residents or businesses that already are established are the only applicants that will (or should) succeed.”

The 3500–3600 blocks of Halsted, with the boarded-up, city-owned Ramova overshadowing an empty street with more than a few bare storefronts, might serve as a general warning sign against greater aldermanic control in zoning and business license matters—and against singling out the businesses that have weathered difficult economic circumstances.

Salons like Antonia’s and Anna’s, or Guyse’s in South Shore, could have packed up and headed for another neighborhood when times were tough—when the theaters closed, or when the recession hit—but they did not.

And newer salons, for now standing in the shadow of the more established institutions or attempting to build other customer bases, may one day step into that position. Or they may close, their spaces remaining empty, until a different business deemed “desirable” expresses interest. It is more likely to be the case in Bridgeport that they remain empty, if precedent is any example.

Although Alberto Murillo was not opposed to Thompson’s ordinance rezoning his building, he did express confidence in the community’s power to support or reject a business over time, without the aid of ad hoc regulation from the ward office.

“The community really decides what’s successful,” said Alberto Murillo, “and that’s really what I’ve seen, being there for so long.”

Nicole Bond contributed reporting for this story.

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.

What is the date of this article?