In August, the Pritzker Traubert Foundation’s inaugural Chicago Prize awarded $10 million to an Auburn Gresham community development project. The Prize competition, seeking to fund a project “using physical development to spur economic activity,” was a citywide spectacle, as the judges whittled down an initial eighty entrants to six finalists before choosing the sole winner. The five other finalists continue to do essential neighborhood work, often where the city fails. These projects, like the one from Auburn Gresham that took the purse, are the visions of self-determined Black and brown communities. All six also still face a significant funding gap.

The Greater Auburn Gresham Development Corporation, in partnership with Urban Growers Collective and Green ERA, won the Chicago Prize with “Always Growing Auburn Gresham,” a multi-site plan that includes a “healthy lifestyle hub” at 79th and Halsted and an urban farming campus at 83rd and Halsted. This will bring jobs, food, healthcare, and money into the neighborhood, while also creating an anchor of growth in an area that has withstood decades of racist city policy, redlining, and other forms of systemic disinvestment.

“In 2021 there are going to be cranes lighting the sky of Auburn Gresham,” said Carlos Nelson, CEO of the Greater Auburn-Gresham Development Corporation (GAGDC).

In addition to Prize funding, The Auburn Gresham plan also received $4 million in federal CARES Act funding, which the city directed in support of Invest South/West, Lori Lightfoot’s South and West Side development initiative.

The five other finalists will each be able to apply for a $500,000 matching grant from the Pritzker Traubert Foundation (PTF), a philanthropic effort from billionaire former Secretary of Commerce Penny Pritzker—Governor Pritzker’s sister— and her husband Bryan Traubert. These projects are located across Chicago’s South and West Sides, in Austin, North Lawndale, Englewood, Little Village, and South Chicago.

While these projects didn’t receive PTF’s main prize, their principals remain undeterred in organizing, planning, and bringing growth.

The Chicago Prize was able to elevate six well-planned, community-developed projects. But these projects and the people behind them say they aren’t relying on philanthropy to get their work done; they’re relying on each other. Perhaps the greatest success of the Chicago Prize is that it gave a citywide platform to the ongoing, deeply collaborative relationships between neighborhood leaders working toward equity across the city.

“Neighborhoods like [Little Village] continually go through being studied. There’s study after study done around development and what’s right for this community. But very rarely does our actual voice get included in that,” said Kim Wasserman, executive director of the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO).

Due to its location along the Sanitary & Ship Canal, Little Village has long been home to heavy industry, and residents are left to shoulder the burden of the pollution created by it. Earlier this year, Hilco Developers demolished a smokestack at the Crawford plant, sending a toxic cloud of airborne pollutants across the neighborhood. Little Village and other Southwest Side neighborhoods have also been hit especially hard by COVID-19. LVEJO’s Chicago Prize-finalist project, “Centro de Solidaridad Mi Villita,” is a culmination of years of research and organizing. When Little Village’s Crawford Coal Power Plant closed in 2012, LVEJO began working with the Delta Institute to engage with residents on what they wanted to do with that space. LVEJO and the Delta Institute continued working together to identify and catalog vacant neighborhood brownfields for remediation and reuse. One vacant site included in the report, a former fire station at 2358 South Whipple Street, became the centerpiece of their prize bid.

“What we heard overwhelmingly from the community was an interest in food,” Wasserman said. Many Little Village residents have experience and skills with gardening or agriculture that they are unable to put to use. “We have a quarter-acre garden in the neighborhood and it’s at capacity with a waiting list every year. There’s just not enough land to go around and the land that we do have is highly contaminated.”

Under the plan, the fire station would be transformed into a multi-use food access center to support the neighborhood’s often-marginalized street vendor economy; Little Village has the second-highest grossing economic corridor in the city, and street vendors are a large part of that economy. Centro de Solidaridad would house cart maintenance and storage, a commercial kitchen, and a retail space for local growers to sell their food. The project would address material needs of the community while also emphasizing that the most marginalized in the neighborhood have a space in their own community.

In South Chicago, a similar fight over the twin issues of economic and environmental justice is taking place. South Chicago and Little Village are the two neighborhoods most affected by pollution. “With our history being steel mill history, people say that was the heyday. We don’t believe that that’s our last heyday, we don’t believe that our community has died,” said Angela Hurlock, executive director of Claretian Associates.

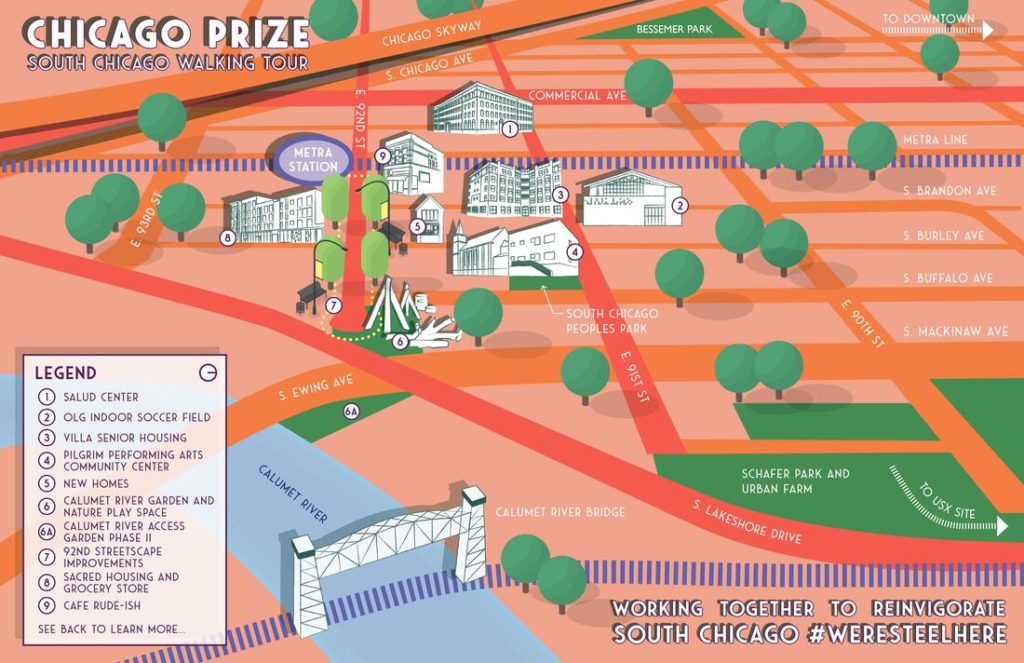

Claretian Associates is the lead agency for South Chicago’s Prize-finalist bid, “We’re Steel Here.” Their proposal includes nine different projects, all already in some phase of development, on 91st and 92nd Streets between Commercial Avenue and the Calumet River. The plan calls for housing, community spaces, and open green areas, all with the goal of creating, as Hurlock calls it, a “community of choice.” A community of choice, according to Claretian Associates, is a neighborhood where residents are making the active choice to put down roots—it is “resident-led, has affordable housing, a thriving business corridor, cultural and recreational spaces, and there’s wealth-building opportunities.”.

The Chicago Prize, while being a substantial opportunity, was not the catalyst for these projects. “Our project was not created for the Chicago Prize submission. We’ve been working on a lot of these projects for years, a couple of them a decade,” Hurlock said.

Austin’s ASPIRE Initiative, which calls for childcare services, early education, and an emphasis on a cradle-to-career pipeline, “was really born from the plan,” said Darnell Shields of Austin Coming Together. That plan he’s referring to is Austin’s Quality of Life plan.

South Chicago, Englewood, Austin, and many other neighborhoods across the city have Quality of Life plans, assessments that include comprehensive community input on what residents want and need in their communities. These plans have been years in the making, and most of the five finalists are aligned with their own neighborhoods’ Quality of Life plan.

The process of synthesizing a neighborhood’s wants, needs, and voice into an actionable document is impressive in and of itself. These plans aim to create an achievable mandate, a set of ideas created by a coalition of neighborhood members. The plans address the wide-ranging issues affecting Black and brown neighborhoods across the city: healthcare, worthwhile employment, food access, and safety. These community goals take on different physical manifestations. Some projects, like those in Auburn Gresham and Little Village, are focused on building multi-purpose spaces. In Englewood, the “Go Green on Racine” initiative, another Chicago Prize finalist, will support job training, healthcare, and food access on one campus.

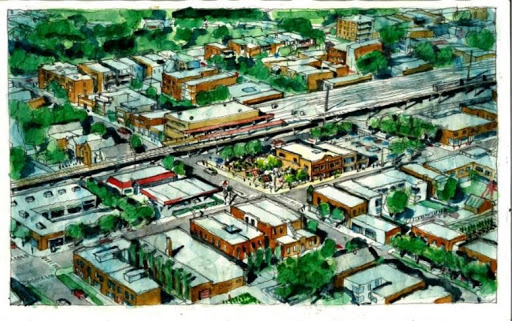

Like South Chicago, bids from Austin and North Lawndale are taking a different approach, eyeing many different stakeholders within a defined area, sometimes encompassing entire business corridors. On the West Side, neighborhood leaders are attempting to right decades of racist disinvestment, and due to their respective Quality of Life plans, they’re doing so with a mandate from their communities.

In North Lawndale, work had already begun on the projects that would make up their Chicago Prize bid years before the Chicago Prize existed. “We had not had a comprehensive plan for North Lawndale … in over fifty years,” said Richard Townsell of the Lawndale Christian Development Corporation. “It’s democracy at work.”

North Lawndale’s proposal contains six different developments, with the goal of increasing affordable housing, workforce assistance, and Ogden Commons, a mixed-use development that will have a partially federally-funded ambulatory care center.

Undergirding this entire process is solidarity and collaboration among finalists, and it feels more powerful than any one grant.

“Common consensus, which is largely being led by people outside of the neighborhood, not people of color, is that they had to come in and do something because there were no leaders here…nothing is further from the truth,” Townsell said. “To survive in this country we have to be extremely collaborative.”

These groups have come together, not just to work with each other, but to advocate for each other. “We’ve partnered with almost every other team,” Hurlock said. “Even now we’re still working to say ‘Hey, we all need funding, we don’t need to compete against one another.’ This is what families need, whether they’re on the West or the South Sides.”

While the structure of the Prize was competitive, community leaders are pushing back against the idea that scarcity should breed competitiveness.

“Life is a series of glass empties or glass fulls,” Hurlock said. “Competition is a glass empty. But raising the visibility of organizations that might not have had that…I’m grateful for the visibility it gave us.”

“We [were] involved in a process that [was] designed to pit us against each other, but at the end of the day…we all care about our community and care about our city and care about our neighbors. It was nothing for us to continue to work together…to just join hands…not just in our respective communities but across the city,” Darnell Shields said.

There is a shared sense of community among the project teams. “I do wish there was an opportunity to foster more cross-pollination,” Carlos Nelson said. “I know competitions are en vogue, but you’re talking about close partners and friends and agencies in an area of dire need. I just wish there was a way to all get together and work on some join efforts that connect each community project.”

None of these projects are yet fully funded. Even the Auburn Gresham group has gaps in their funding that they are still looking to fill. Multiple finalist groups met with Mayor Lightfoot at the beginning of October to discuss ways that they might secure money, hoping that Lightfoot, whose Invest South/West initiative is aimed at stimulating investment in many of the same neighborhoods as those in the running for the Chicago Prize, could work to find corporate or philanthropic donors who might fill in the gaps.

This gets to the question of equitable development, a conversation that Lightfoot has been having regularly throughout her tenure so far as mayor. “That’s why we went to the Mayor,” says Townsell, “in light of her own public conversations around equity, and wealth, and inclusion, that these projects should be priorities.”

Equitable development, or development without displacement, is a strived-for ideal often pursued but rarely attained. These projects offer direct antidotes, and speak to the empowerment of a community from within. “When we talk about equity and inclusion, we’re talking about Black- and brown-run institutions benefiting directly from city investment,” Townsell said.

“Our wish is that all six neighborhoods that were represented … also receive 10 million, 20 million, 40 million, whatever amount is necessary to enact that transformational change,” said Sidney Freitag-Frey, The Delta Institute’s director of development. Nelson has a similarly lofty but more specific number in mind: “Our community needs 100 billion, with a ‘b,’ just to begin catching up to the investment that white communities and suburbs have had over our communities.”

At the heart of these projects is self-determinism, providing the building blocks so as to re-center community needs over the needs of big business. “How do you go from an extractive economy that just takes from us to an economy that gives to us and is regenerative?” Wasserman said. Solutions are not easy, but these projects are at the forefront of the conversation from organizers continuing to do the daily work of building coalitions to shore up power.

Correction, December 14, 2020: This article has been edited to clarify that the $500,000 matching grants have not yet been disbursed.

Jonathan Dale is a freelance journalist focusing on issues related to the urban built environment. He is a Chicago native, and last wrote for the Weekly about the city’s Invest South/West initiative.

Great piece Jonathan!