When Margaret T.G. Burroughs passed away in 2010 at the age of ninety-five, condolences flowed in from across the country. President Barack Obama praised her as an “esteemed artist, historian, educator, and mentor,” and called the DuSable Museum in Washington Park, which she founded, “a beacon of culture and a resource worldwide for African-American history.” But for Purdue University Fort Wayne English professor Mary Ann Cain, author of South Side Venus: The Legacy of Margaret Burroughs, Burroughs’s passing was surprisingly personal. “I felt incredibly sad, unexpectedly…I just felt, you know, really deep, deep loss,” Cain remembered. They were not especially close, but had crossed paths a few times after Burroughs initially helped Cain with background research for a novel. Like many others who met Burroughs, Cain had been touched by Burroughs’s generosity. “She was just so incredibly generous to take time for somebody she didn’t know,” said Cain.

In her book, Cain takes up the challenge of writing the first-ever biography of this important but often overlooked Chicagoan, who was by all accounts not interested in self-promotion. She traces Burroughs’s life through momentous periods in United States history, from the Great Migration, when her family moved from St. Rose, Louisiana when she was five years old to the Civil Rights movement, when she founded what became known as the DuSable Museum of African American History. Although the biography carefully documents these events in Burroughs’s life, Cain sometimes sidesteps the opportunity to offer a sophisticated critique of Burroughs’s role in a historical context. It’s a pity, especially when Cain declines to pursue the interesting questions she raises about Burroughs’s actions during the height of McCarthyism.

One could easily assume that Cain’s anxiety over portraying Burroughs in a negative way may be because Burroughs is so beloved by her contemporaries. “[My intention] was to present her in the light of how people who trusted me with their stories about her saw her,” Cain said during a book talk in June at the Printers Row Lit Fest. She encountered apprehension over the idea of a Burroughs biography from some of the people she interviewed while conducting research for the book. “One person specifically said, ‘If you’re digging up dirt on [Margaret Burroughs] then I’m not participating,’” recalled Cain.

But Cain insists she was not constrained by the expectations of Burroughs’s acquaintances while writing the book. She explained that the “dirt” the interviewee was referring to was the government’s crackdown on activists during the Second Red Scare, during which Burroughs saw her share of harassment. During that period, activist groups were viewed with suspicion, and former activists became much more cautious in order to avoid being labeled communists. This in particular affected Black activist groups. “After the 1938 establishment of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC),” Cain writes, “the persistent efforts during the Popular and Negro People’s Fronts to work across color and other identity lines [were] met with more and more resistance.”

As Cain makes clear in the biography, it was just this kind of work to which Burroughs dedicated her life. She had been civically engaged from an early age, attending NAACP meetings in high school and protesting the arrest of the Scottsboro boys. At DuSable High School, where she taught art, she was known for speaking her mind. She would teach her students about famous Black figures such as Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass in secret because the school disapproved. “I’d look over and see the white principal appear at the classroom door,” Burroughs wrote in her autobiography. “Turning back to the class I’d say, ‘And that’s how Betsy Ross came to sew the flag. Now boys and girls, let’s talk about Patrick Henry…’ As soon as he was gone, we’d go back.” Her motivation was simple: “I just couldn’t see myself standing in front of a group of eager-eyed young black people and not being able to tell them something very positive about themselves.”

Burroughs also had direct ties to communism, both through her activist work and through Charles Burroughs, her second husband, who completed his schooling in the Soviet Union because his mother did not want him to “suffer a Jim Crow-style education”. The two initially crossed paths when Charles was lecturing at a Russian chapter of the International Workers Order and Burroughs was an usher for the event. Their second meeting was at a children’s summer camp whose goal was to “integrate the Marxist principles of unity, equality, and democracy […] into family life.” After they married in 1949, they had famous house gatherings dubbed the Chicago Salon, where famous artists and intellectuals, such as James Balwin and W.E.B. DuBois, passed through and where Charles, who “loved his Russian culture and language and shared it with anyone who cared to listen, s[ang] the praises of his adopted country as a place where he did not suffer the kinds of discrimination endured by his wife.”

In 1951, Burroughs was called in to testify before the Chicago Board of Education. At the time, all teachers had to sign a “loyalty oath” in order to teach. The Board interrogated her about her connections to people with communist affiliations and demanded she reveal the names of other teachers who had Communist sympathies. “Their final directive to me was not to tell anyone about the meeting or the questions,” Burroughs wrote in her autobiography, “but of course as soon as I left the building I called all the teachers I knew to inform them of what had happened and what to expect if they should be called down too.” Cain describes Burroughs, who suspected she was the only teacher subjected to the interrogation, as being “shaken to the core” by the experience.

Cain marks that testimony as a catalyst for some important changes in Burroughs’s life. In 1952, to escape from the pressures of the situation in Chicago, Burroughs took a year-long sabbatical from teaching to live in Mexico, where she met Mexican artists and learned printmaking, a technique she later used to make her signature lithograph prints. It was also in Mexico where, praised by people on the natural curl of her hair, Burroughs got the confidence to stop straightening her hair—an unusual choice in Chicago at the time. A former student said that Burroughs’s early adoption of wearing her hair naturally helped in “communicating a message of racial pride and self-determination to students.”

Burroughs also became less of an activist during this period. Cain writes that “as the 1950s came to a close and civil rights movements began to mature […], Burroughs did not join up or actively promote such events.” Cain thinks Burroughs learned to maintain a low profile, allowing her the ability to continue her “cultural and historic work” that supported her greater mission. “Because a lot of people…their careers were destroyed,” said Cain in an interview, listing artists Charles White and Elizabeth Catlett as people who had to leave Chicago as a result. Cain muses of Charles and Margaret Burroughs: “To what extent did they have to ‘compromise’? Or did they compromise? How did they maintain and still keep their integrity?” It’s unfortunate that instead of exploring these questions, Cain seems primarily concerned with casting Burroughs’s step back from left-wing activism in the best possible light. Cain suggests that had it not been for Burroughs’s adoption of a lower profile, the DuSable Museum itself might not exist.

It’s true that the origin story of the DuSable Museum includes some savvy political maneuvering by Burroughs. The museum started as the Ebony Museum of Negro History and Art on the first floor of Burroughs’s home, with a small collection that she expanded by sending out letters requesting donations to exhibit and writing to “foundations and businesses for funds.” In 1968, community pressure was building for a museum to celebrate the Black settler Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable. Burroughs took advantage of this by contacting the mayor’s office and offering to change the museum’s name to DuSable, which would give the museum official status as a DuSable monument, along with receiving $10,000 from the City. When the museum grew too big for the Burroughs home, she petitioned the Chicago Parks Commission for the use of a vacant Chicago Police Department building in Washington Park. “Students wrote the superintendent and copied their letters to the mayor. As Burroughs recalled, ‘Luckily election year was coming up, and I guess the mayor [Richard J. Daley] figured it might look…good to see his picture in the paper presenting me with the keys to this building.’”

Cain said it would be interesting for future Burroughs biographers to catalog the “full breadth of her accomplishments as an artist”. “Most people know her by the linocut prints,” said Cain, “but she was a sculptor, she was a painter.” Cain pointed to Burroughs’s hefty five hundred page surveillance file, compiled by the government during the McCarthy era, and the DuSable Museum’s trove of articles, short stories, and letters Burroughs wrote. These materials became available within the last few years, as rich resources Cain wasn’t able to properly explore due to time constraints.

It’s exciting that there are many more primary sources of Burroughs still waiting to be tapped, because it’s when Cain quotes directly from Burroughs’s own writing, such as her 2003 autobiography, Life with Margaret, that Burroughs comes most alive.

Burroughs is a wonderful writer. Events as large as the Great Migration are made personal through her eyes. In the autobiography, she recalls her excitement as a child taking the train to Chicago with her family, even though they sat in the noisy car behind the engine designated for Black travelers and Burroughs, who was big for her age, had to walk around with her knees bent so the conductor wouldn’t charge them extra. “Many noisy, arduous hours later we arrived in Chicago, a marvel of a place,” she wrote, “We had never seen anything like Chicago, with all its buildings, bigness and people—all sorts of people. We instantly liked it.”

Burroughs provides interesting historical commentary as well, especially when she excoriates the US government for pushing Black activists toward socialism by “watching us as if we were criminals”, and then “offer[ing] us the unpleasant choice of renouncing socialist leanings in order to win greater civil rights freedoms—which seemed a near acknowledgement that civil rights was our only goal in the first place.”

Life with Margaret is sprinkled throughout with origin stories, humorous anecdotes, general advice, and poetry, including an especially moving piece written to her husband Charles after his death. But the best writing Burroughs does is early on when she describes her early life before moving to Chicago, when she was living with her tight-knit family in St. Rose, Louisiana.

“As children, we enjoyed the freedom of the open fields and of dangling our feet in the Mississippi when it flowed up to the levee,” Burroughs writes. “We would stand out by the station and watch the big Illinois Central trains snort in from Chicago and all up and down the Mississippi. Or sometimes we’d stand in front of the General Store on Big Street, which was white-owned, and enviously watch the white kids skate around on their roller skates.”

Though Burroughs later looked back on her childhood in Louisiana with a new understanding of the role racism played, she carried an appreciation for the power of community with her to Chicago. “It was wonderful growing up in a community of people who cared so much for one another,” she writes. “We were a team because we had to be; we had to work together to survive. There is a certain strength that comes from pulling together, working together, laughing and crying together.”

This sense of community is a legacy Burroughs leaves behind in Chicago, felt not just in the institutions that she helped build, but in places like the acclaimed Yassa African Restaurant in Bronzeville, where a painting of Burroughs overlooks the room, or the latest album by Jamila Woods, the title of which is inspired by one of Burroughs’s poems, or the recently dedicated mural coordinated by an art instructor at Stateville Correctional Center, where Burroughs taught for many years.

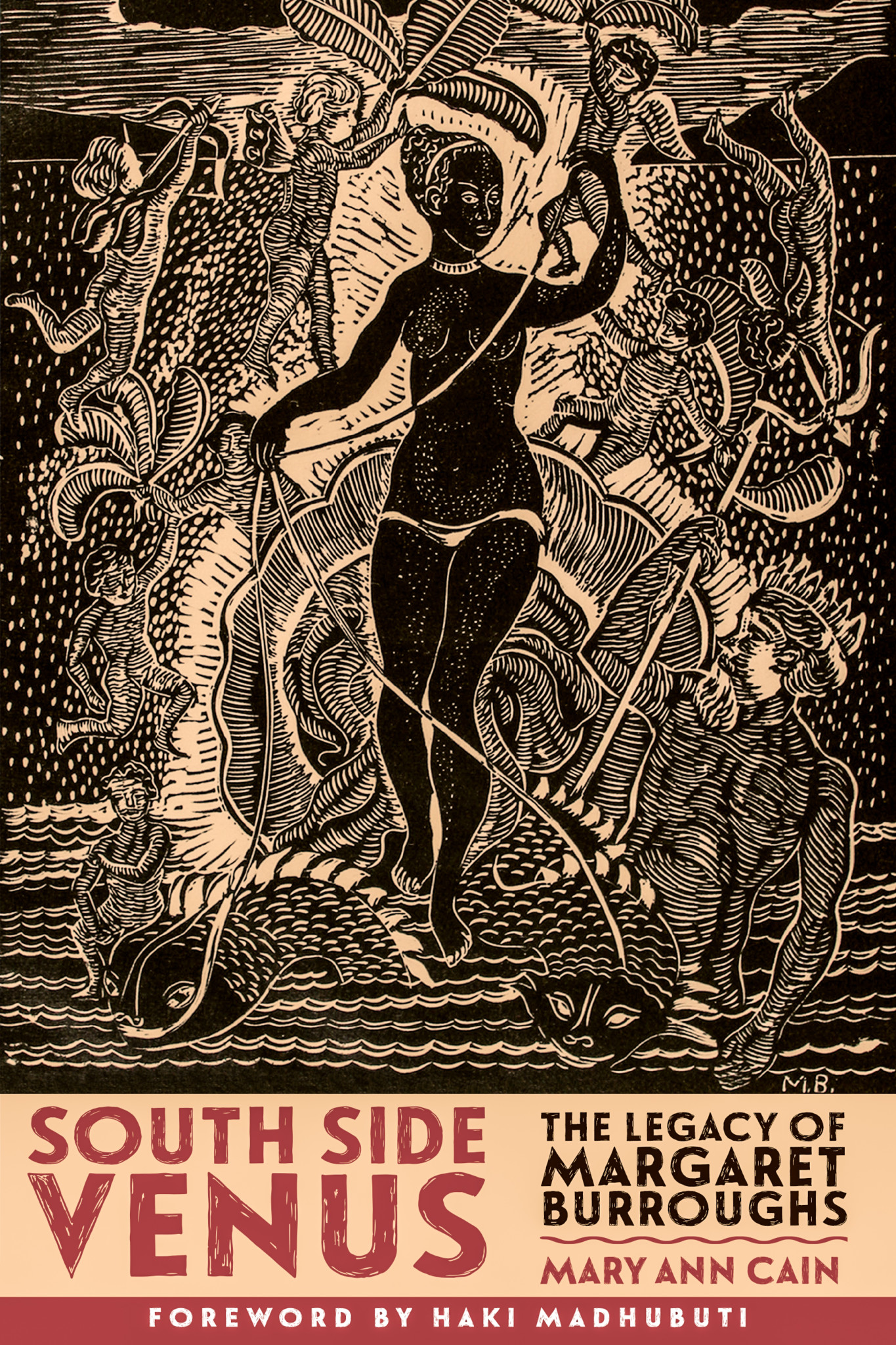

Cain explained that she titled her biography South Side Venus because Venus was the goddess of love. Burroughs had always been all about “love of self, love of people, love of community,” Cain said. “Margaret was all about love.”

Mary Ann Cain, South Side Venus: The Legacy of Margaret Burroughs. $18.95. Northwestern University Press. 240 pages

Tammy Xu is a contributor to the Weekly. She last wrote for the Weekly in April about the Richland Center food court in Chinatown.