Between four horn players, a dancing woman throws up her hands and closes her eyes. The performers are in a crowd in the middle of a street illuminated by streetlights, golden shopfront windows, and the stars overhead. Faces look out from windows. A white police officer casts a shifty glance.

In a Columbia College Chicago lecture hall on Michigan Avenue, an audience of several dozen sat before this 1936 portrait of nocturnal revelry, which its painter, Archibald J. Motley Jr., called “Street Scene.”

“This is not a scientific translation of light’s properties,” Richard Powell said from behind a lectern, “but an aesthetics of shine in African-American culture.”

The audience had come for the opening lecture of “Unfinished Business! The South Side and Chicago Art,” a two-day symposium in late October organized by the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago, Columbia’s Museum of Contemporary Photography, and Northwestern University’s Department of Art History. The lectures and panels addressed the South Side’s historic significance and the institutions and artists that often go unrecognized, despite their continued impact on Chicago at large.

As he discussed “Street Scene” and works by other artists, Powell, a professor of art and art history at Duke University, probed the term “South Side:” a place-based shorthand for a culture, community, and body of ideas that has changed over the years.

Motley, like Margaret Burroughs and many other Chicago artists, came to the city from the South during the Great Migration. Those people who went north for an undefined idea of possibility built what Horace Cayton and St. Clair Drake would call the Black Metropolis—and what Powell, acknowledging Harlem’s mystique, calls “the other African-American urban Mecca.”

This other place, centered on 35th and State Street in the first half of the twentieth century, was unique. Powell connected Motley’s use of magical color in his night scenes to the color-consciousness celebrated by Chicago businessman Anthony Overton’s cosmetics line. Overton, who also owned the Chicago Bee newspaper, lobbied for changing the name of Drake and Cayton’s Black Metropolis to Bronzeville, reflecting his interest in the marketing of skin tones. In Chicago, “self-adornment, modernity, and capitalism found a common purpose,” Powell explained.

The packed streets and glowing shops in Motley’s paintings suggest that a walk through Bronzeville was a visceral experience of capitalism. Chicago’s Black publishing industry, which would eventually feature Johnson Publishing Company’s Ebony, Jet, and Black World, possessed an “entrepreneurial, commercial sensibility,” as Powell put it, which inspired designers, writers and artists to think, “What I do has to reach out to people, to communicate with people wherever they are.” In the dark outside, several blocks south of the lecture hall where Powell spoke about this marriage of art, culture and marketing, the Johnson Publishing Company’s Ebony and Jet sign still stands in Chicago’s skyline.

The second day of the symposium continued with panels and lectures at the University of Chicago’s Logan Center for the Arts. Artist Faheem Majeed spoke about the Floating Museum project, which draws attention to different places around the city using, among other installations, a bus-sized, tilted sculpture of Jean Baptiste Point du Sable’s head. It looks like a lost artifact emerging from the ground. “Chicago could easily be called DuSable,” Majeed said, while images of the yellow sculpture flashed on the screen behind him. “You all know who DuSable is? If you don’t, you need to look it up.”

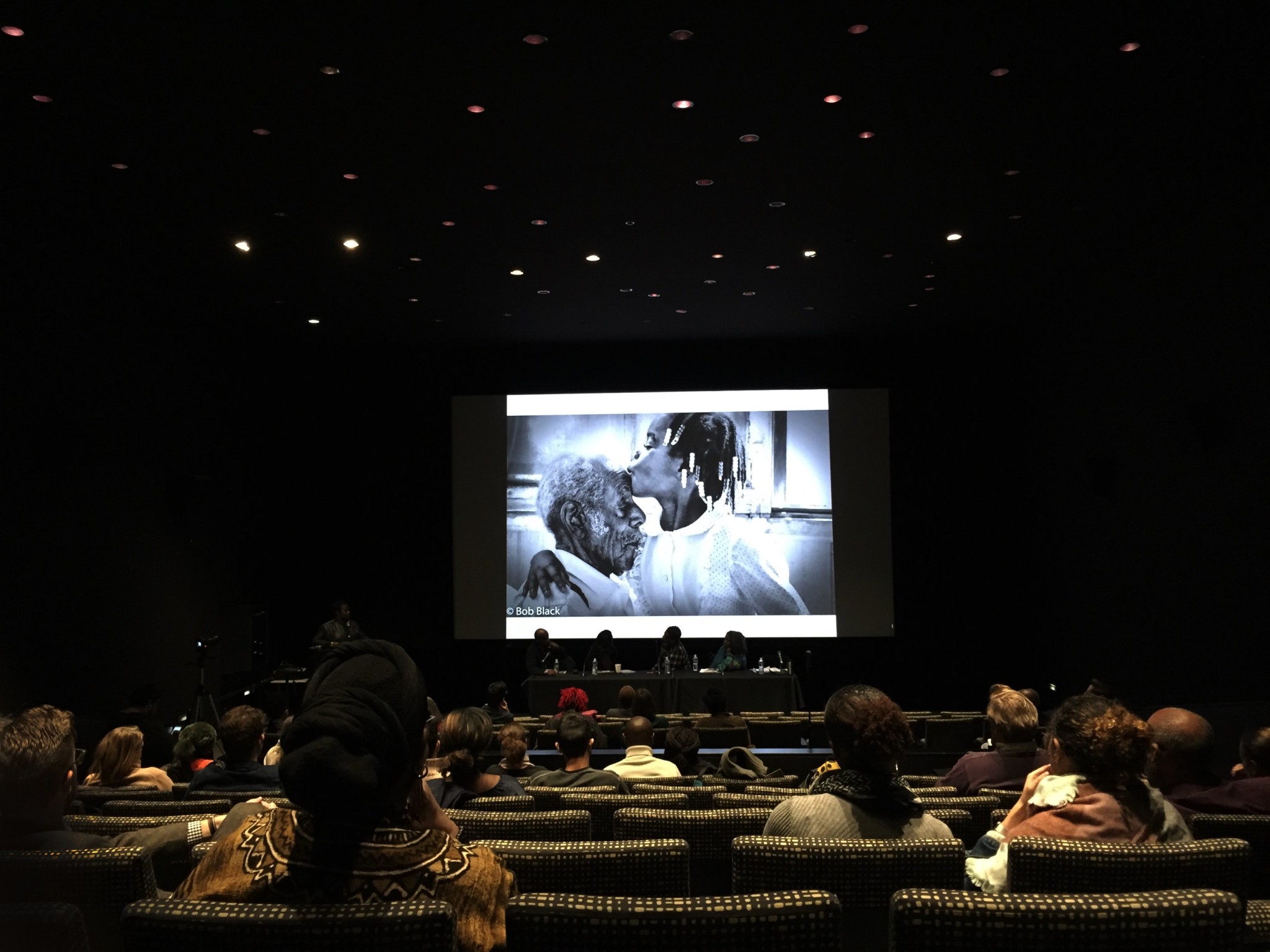

Later, the audience looked at a photograph by Bob Black of a young girl kissing a wrinkled man’s forehead. She was the man’s sixth-generation granddaughter, Black explained. When Black had asked his subject what he thought when cars first appeared, the aging man said, “Oh, we didn’t think that was going to last long.”

After a buffet lunch eaten around a single, long table in an adjacent room, the attendees and speakers returned in chatting twos and threes to the lecture hall. Kai Parker, a doctoral candidate in history at the University of Chicago, spoke to the audience about his work gathering the collaborative oral and musical history of a long-shuttered jazz jam in an alley on 50th Street. While the author Richard Wright wrote that Chicago was “the known city”—known by statistics which suggest “how it is run, how it kills”—Parker said that the Alley LP was about knowing the city in different ways. “You can’t know Chicago only from news reports…and presidential candidates,” he said. Sandra Swift, a Sojourner Scholar alum and collaborator on the Alley LP, explained that the alley became a place because of the work of under-represented musicians and artists. “If you’re going to live here, you need to know them,” they said.

But before following Swift’s advice and getting to know people like Siddha Webber, Mitchell Caton, or Daniel “Sandman” Pope, stop at the DuSable Museum of African American History to become acquainted with another artist’s work at “The Art and Influence of Dr. Margaret T. Burroughs, 1960-1980,” an exhibition running from September to March.

Of the hundreds of artists mentioned at the symposium, no one encapsulated place, art, and the South Side like Burroughs. She shares with many others her northward migration to the Black Metropolis—but once there, she made not only art, but institutions. Twelve years before the DuSable Museum moved to Washington Park in 1973, it was known as the Ebony Museum of Negro History and Art and located on the first floor of Burroughs’s home. She founded it.

The DuSable’s Skyla Hearn and Erica Griffin curated the Burroughs exhibit around four themes. The works of Alonzo S. Pashman, Ralph Arnold, Charles White, and others hang as testament to Burroughs’s efforts as a mentor. A Burroughs print of Malcolm X showcases her role as an anti-racist activist. A bronze sculpture, “Crown Head of an Oni,” demonstrates her work as a multimedia creator. And in a separate room, objects and images from the institutions that Burroughs established—like the Lake Meadows Art Fair and the DuSable Museum itself—speak to her role as a placemaker.

But other pieces in the exhibition challenge these neat divisions in the work of an artist who identified as a humanist and who strove for “the liberation of my people in particular, and broadly, for the end of imperialist oppression of all underprivileged people of the earth.” An Arkee Chaney sculpture of a Black man in an electric chair entitled “Government Premeditated Murder” calls attention to Burroughs’s volunteer work in local jails. Burroughs also wrote collections of poetry, including “What Shall I Tell My Children Who Are Black?”

At the symposium, Majeed asked the audience: “Has anyone had Dr. Burroughs jump into their car?” A woman raised her hand and several people nodded. “Take me to the bank…let’s get cat food…take me home,” Majeed recounted. “I loved that woman.”

On a recent Sunday, a steady stream of museumgoers passed through the exhibit. Some wandered from drawing to sculpture to print, seemingly confused by the lack of explanatory text on individual pieces. Others surveyed the gallery more methodically, and one pair of visitors entered into a heated debate over the use of swastikas in a Leopold Mendez print.

Burroughs’s print of Mahalia Jackson shows her connection to Bronzeville, to the South Side, and to Chicago. Her bold lines recall her time working with artists in Mexico City. And the artist’s African aesthetic hints at her extensive travels there in the 1960s, when she was one of the few Chicago artists to engage with the continent. Powell had said at the symposium that Black artists in Chicago often saw themselves as “local, national, and global” all at once.

But even at those three scales, Parker reminded a hushed audience that “Black culture is not floating in the abstract, but is located in specific places.”

The night before, back on Michigan Avenue, Powell told the audience that during a trip to South Africa in the nineties, a resident had approached him and asked: “Are you African-American?” He responded yes. “Well, you must know Margaret Burroughs!” she exclaimed.

And yes, he did.

“South Side Stories — The Art and Influence of Dr. Margaret T. Burroughs, 1960–1980.” DuSable Museum of African American History, 740 E. 56th Pl. Through March 4. dusablemuseum.org

Max Budovitch is a contributor to the Weekly. He recently wrote a piece about the history and future of Woodlawn.