Historically, agriculture and urban planning have had a tight-knit but fraught relationship. In the lower-income neighborhoods of nineteenth-century American cities, livestock—necessary sources of food and wealth—were common, as were concerns about the public health consequences of dense tenements clustered with people and pigs. Some early attempts at outlawing animals for sanitary reasons were met with public derision: As the New York Times reported in 1865 in response to the apparent arrest of a cow in New York City, “The spectacle of ten or twelve policemen guarding a solitary cow on her way to the cattle-jail provokes too much merriment even for those who are interested in having the streets kept clear of four-footed nuisances.” But over the course of the nineteenth century, the expanding power of the field of public health in urban planning meant that many forms of urban agriculture, particularly those involving animals, were significantly curbed.

Urban agricultural practices reemerged in force during the 1970s, when suburbanization and the widespread demise of manufacturing created neglected city cores dotted with vacant lots. Gardens sprouted up in response, the result of neighborhood residents reclaiming abandoned land for their own purposes. And while this version didn’t involve driving hogs through streets, it relied on a similar principle of self-sufficiency, as prospective gardeners cleared out sites littered with detritus, replaced blacktop with topsoil, and canvassed cities for equipment donations. Now, community gardens and urban farms sit snugly within residential, business, and industrial districts. They serve as educational spaces, supply local farmers markets, and beautify their neighborhoods. By 2012, a Google Earth survey by researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Department of Crop Sciences found that Chicago had 4,648 sites of food production, most of them small residential gardens.

Chicago’s city planners were slow to catch up to the ubiquity of the city’s gardens and farms. (They weren’t unusual in this regard—a few cities, like Boston, created open space designations in the eighties that allowed for community gardens, but most had no clear land-use provisions for urban agriculture.) It wasn’t until 2011 that the city finally recognized urban agriculture in its zoning code, creating land-use designations for both urban farms and community gardens. And while some urban farmers still believe further changes are necessary, others are focused on another initiative: clearing up the complicated, often prohibitive business licensing process that currently exists for commercial growers.

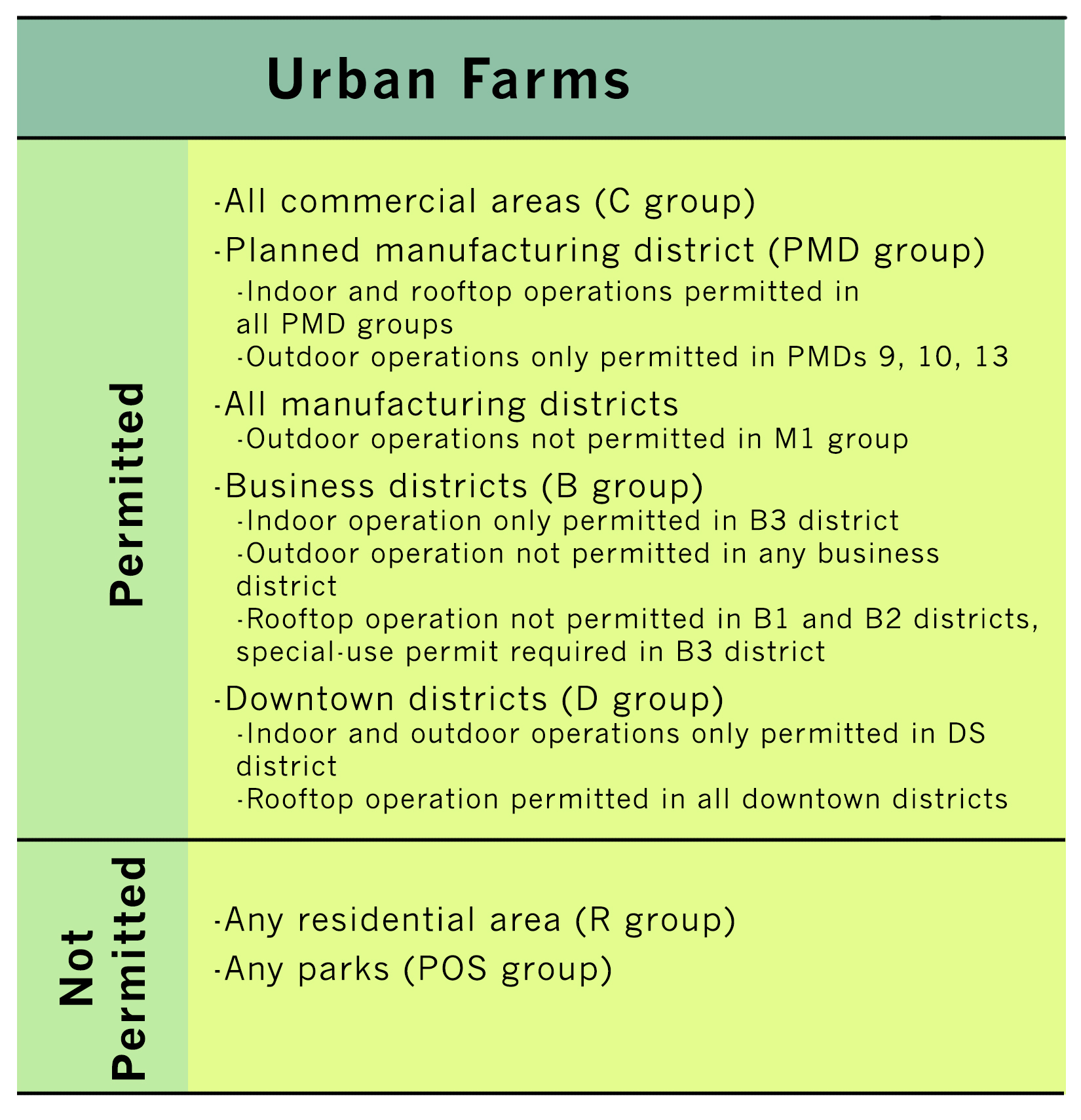

The 2011 zoning amendment created and defined two types of agriculture permitted in the city—urban farms and community gardens. Urban farms are just what they sound like: larger-scale agricultural operations where produce is grown to be sold. They’re usually permitted “by right”—meaning that you don’t have to obtain a special permit to operate one—in non-residential areas, mostly parts of the city zoned for business and manufacturing. There are exceptions to this general rule; rooftop urban farms, akin to the non-commercial garden atop City Hall, are allowed in all downtown areas.

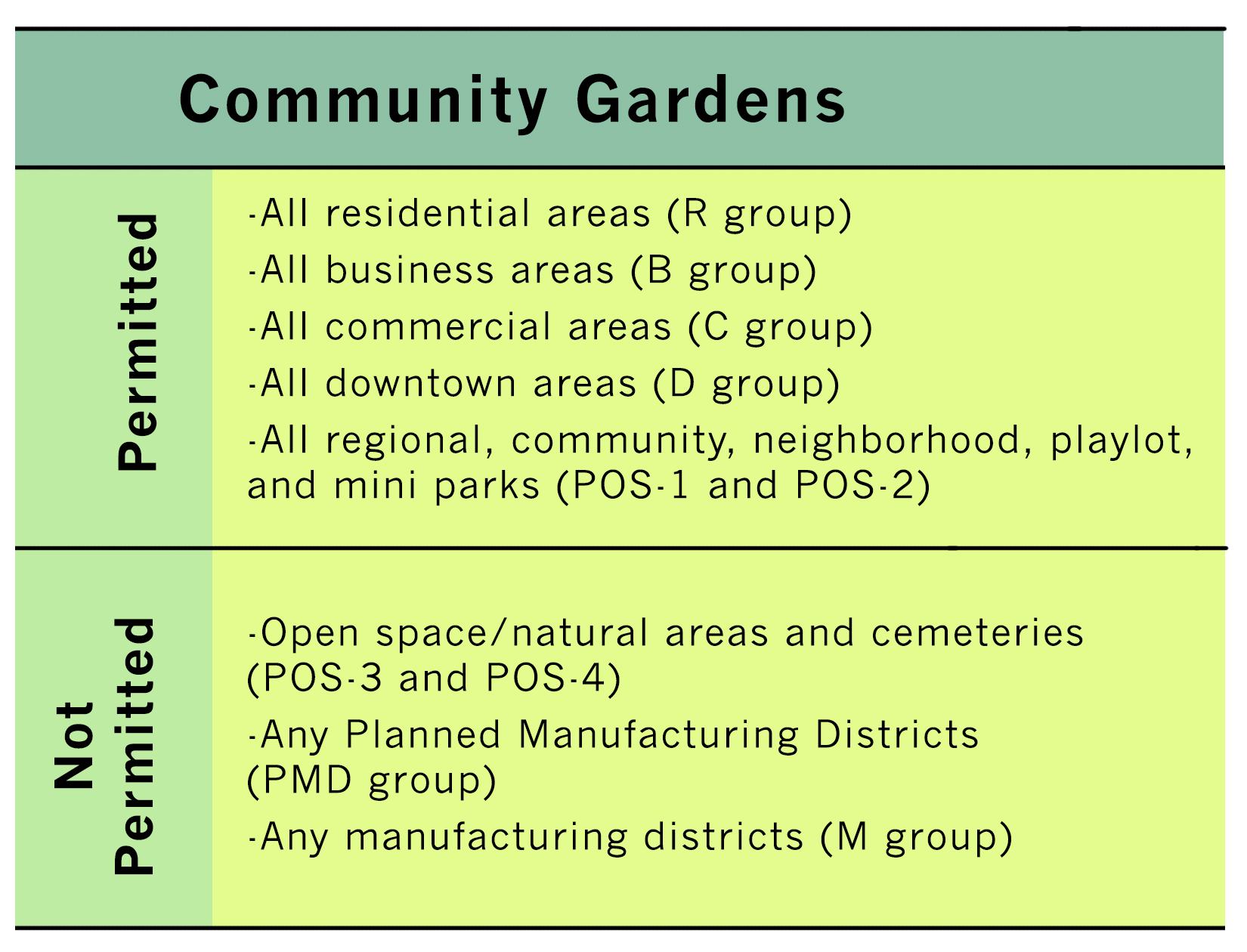

On the other side, community gardens, often smaller than urban farms, are meant to function as spaces for “beautification, education, recreation, community distribution, or personal use” within a particular neighborhood. They’re permitted in pretty much every part of the city except areas zoned for manufacturing. Though owners—usually a nonprofit or neighborhood organization—aren’t allowed to run dedicated commercial operations, “incidental sales” are fair game, and don’t require the owner to get a business license.

“People have had vegetable gardens going way back. In Chicago, because it was a big meat industry city, people had backyard chickens, geese, peafowl. They call it an incidental use, a use that’s normal or expected.,” said Abe Lentner, an adjunct lecturer in the College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “Everyone probably knows people who sell things on Etsy… Just because you sell a few things that you make doesn’t make it a home-based business.”

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly

The amendment also established certain building requirements for agricultural plots: urban farms, for example, must have fencing and screening, as well as parking for employees. That’s frustrated some farmers, who think the stipulations act as restraints on the possible flexibility created by farming in a city, particularly one with plenty of vacant land on the South and West Sides. “You have to say, here, we don’t need to put in parking because nobody lives on the block anyway…. We shouldn’t put all of this permanent infrastructure as if it were a permanent business,” said Ken Dunn, founder of the Resource Center, a nonprofit environmental organization.

Dunn’s Resource Center runs City Farm, a farm that operates on vacant land and shifts locations every couple of years when the plot it’s working on is slated for development. From 2011 to 2014, it ran a farm at 57th Street and Perry in Washington Park, until the city decided not to extend the lease. It moved into a vacant lot near the old Cabrini-Green public housing complex in the early 2000s, then left at the end of 2015 to make way for a mixed-use development. The farm’s transience is its point: it provides work for neighborhood on land that would normally remain idle.

Dunn believes the city should institute the City Farm model on a large scale, temporarily turning many of the city’s vacant properties into short-term urban farms that would benefit communities with high unemployment rates. “We have to realize that we are in an emergency situation in our city, as well as more broadly…. If [people] need jobs, we bring them, no matter how glamorous,” he said, estimating that Resource Center farms can generate up to $150,000 per year per acre in revenue by selling to and composting for high-end restaurants. “We need a solution in the next few months, or the next year or two. We’re in trouble: let’s look at what we can do.”

For Dunn, then, the strength of urban farming lies in its flexibility, the temporary reprieve it can provide by easily moving in and out of economically depressed areas; Lentner, for his part, thinks the benefit of urban farming is its proximity to the city’s core. On most metrics, farming outside the city is the fiscally prudent choice: land, taxes, and labor costs all tend to be cheaper. But the comparative advantage of an urban farm lies in its easy access to food vendors and restaurants. To take advantage of it, Lentner says, city farmers have to go beyond “just producing tomatoes… [Instead], take the raw product, prepare it in a certain way and deliver that. If you were raising chickens in the city at a large scale, you wouldn’t just sell eggs, but would sell quiches, because you have a much greater ability to make a living than just simple production of commodities.”

Actually selling their products, though, has been a surprisingly tricky process for many farmers to navigate. Currently, farmers largely have two business licenses available to them: a peddler’s license for small-scale farmers, and a wholesale license for bigger operations. Both have their disadvantages, according to the Chicago Food Policy Action Council (CFPAC). If a farm has a peddler’s license, each person in the business has to buy their own, which can get expensive, and there are restrictions on when and how they can sell their produce. A wholesale license works well for the biggest farms, like Gotham Greens in Pullman, but isn’t a good option for more mid-size businesses because of onerous infrastructure and inspection requirements.

Because those options are insufficient, and the licensing process at the city’s Department of Business Affairs and Consumer Protection (BACP) can be confusing, many farmers operate without a license. “Most people just don’t have a license, and they’re operating in a grey space where there’s no [obvious] license to go for,” said Lauralyn Clawson of Urban Growers Collective, an organization that helps communities develop sustainable food systems.

Clawson is also the co-chair of a CFPAC working group proposing a modified version of a third existing business license for urban farmers, an effort that’s been gradually building momentum over the past three years. The CFPAC working group has already met with the city once, and plans to present its proposal to the city in two weeks. “After that, it depends on how quickly the City moves on it,”said Simms.

CFPAC is pushing for a modified license because it can’t create a new one; in 2012, Mayor Rahm Emanuel charged BACP with cutting its number of licenses and to largely refrain from creating new ones. (It’s not a complete moratorium: on April 18, for instance, the city announced a new license for mobile boutiques.) Instead, the working group wants to modify the mobile food business license for produce merchants. The mobile produce merchant license was initially created to accommodate initiatives like StreetWise’s Neighbor Carts, a program designed to help homeless people earn revenue by operating traveling produce stands.

As written, the license is unnecessarily restrictive to urban agriculture. Because part of the purpose of Neighbor Carts was to encourage healthier options in food deserts, one of the license’s requirements was that at least fifty percent of produce merchant business take place within areas underserved by grocery stores. This presents an obstacle for farms that aren’t already located in areas defined by the city as “underserved,” which can still include neighborhoods with low healthy food access. The CFPAC working group has presented several possible solutions to this problem, including suggestions that the requirement be reduced, or replaced with a more general requirement.

Still, Sims and Clawson emphasize that the point is not to eliminate the requirement entirely, just to make it more manageable. “We’ve gotten feedback from communities around [the fifty percent] number. In general we think that there should be some number that would encourage and really require businesses to give back to the communities in which they’re farming,” Clawson said.

Nick Lucas, the programs manager at Advocates for Urban Agriculture, one of the groups working with CFPAC on the proposal, echoed this point. “The mobile produce merchant license was focused on increasing food access, and that’s something we very much care about,” he said.

Ultimately, the zoning amendment, business licenses, and the discussions around both initiatives reflect a broader aim of food policy advocates: minimizing the cost of selling produce or starting a garden, thereby ensuring that the fruits of urban agriculture are distributed more equally. As Lucas put it, “Urban farms should have the lowest possible barrier to entry. And that’s what we want from this business license—not expensive and straightforward.”

Christian Belanger is a senior editor at the Weekly and a reporting fellow at City Bureau. He’s lived in Chicago since 2013. Currently in Bridgeport, he enjoys long walks up the Palmisano Park hill, and burning vegetables he means to roast. He also wrote this week about Far Southeast Side activism around the area’s zoning for manufacturing for the Weekly.