For five years, the beloved DIY arts festival 2nd Floor Rear has teamed up with Chicago artists to bring ephemeral and experimental exhibits to apartments, backyards, and alternative art venues across the city. In years past, the festival took place largely in North Side neighborhoods, but this year 2nd Floor Rear split its over thirty events between two days and the neighborhoods around two CTA train lines: the Blue and the Pink. Three Weekly writers set out for Avondale and Pilsen last weekend to take part in the festivities. They returned with accounts of forts and kazoos, vibrantly colored dresses, and a temporary greenhouse. (Emeline Posner)

FORT (at the edge of chaos)

by Christopher Good

There’s a bright red message scrawled on the sign hanging from the door: “IF YOU WANT TO KNOW A SECRET KNOCK 3 TIMES.” I’m in Pilsen, a few blocks south of 18th Street, and against my better judgment, I’ve knocked three times.

At once, the door cracks open and a wary pair of eyes looks me over. A voice grills me about the secret I want to know. After I stammer out an apologetic question about the pillow fort I’d heard about online, the door swings open and I’m escorted inside.

It takes a moment for me to untie my shoes and adjust to the dim lighting, but as I squint at the draped linens and the cross-legged crowd, I realize I am standing (or stooping) within “FORT,” a performance art installation staged as part of 2nd Floor Rear. It doesn’t take long for me to realize that, as promised, “FORT” is poised right at “the edge of chaos.”

John Harness and Grace Needlman, the organizers of the piece, described the event online as a “comforting, playful environment for confronting uncomfortable ideas.” Sequestered within the screwball trappings of a pillow fort, I’m told, there is a capital-E Experience.

Blankets are draped across the ceiling; crustless cream cheese and cucumber sandwiches are spread across a kitchen countertop. Someone is strumming campfire songs on an acoustic guitar, and everyone’s playing along with bright plastic kazoos. (As I fold a bright sheet of construction paper into a crown, I’m told that the kazoos are to be used “in the event of a cave-in.”)

Several sandwiches later, the fort is ready. I start crawling through a tight passageway on my hands and knees, and only seconds later I am startled by a loud noise. Previously hidden beneath a mound of stainless steel pots and pans, a woman in a grey blazer and equally grey face paint blocks my path. She introduces herself as “the Wall” and asks me who I deny.

Later confrontations are only more absurd: first, I’m scolded by a woman in librarian cat-eye glasses for making an unsatisfactory paper snowflake, then I’m yelled at by a “snowflake assessment committee.” At times, I’m not sure whether to laugh, take offense, or sit in silence. My paper snowflake is stolen by a raccoon hand puppet; I play a game of chess with Scrabble tiles and dice. At the end, a scepter-wielding princess asks me how everything went, and for the life of me, I can’t think of a straight answer.

I can’t say if everyone would have enjoyed “FORT” as much as I did, but never let it be said that John Harness, Grace Needlman, and their cast of actors settled at just a pillow fort.

Hot House

by Stephen Urchick

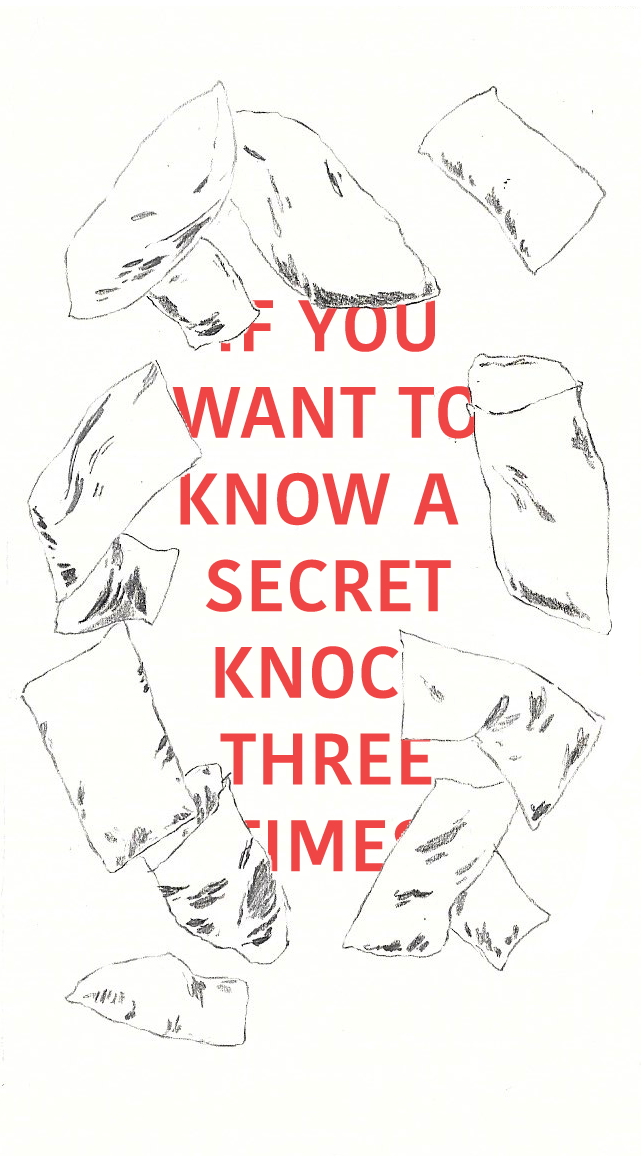

The pop-up exhibit “Hot House” felt less like a greenhouse than a drive-in—a chance to stop by, look over a few bite-sized pieces of contemporary art, chat up the artists, and head back out. Julia Klein, Curt Miller, and John Szczepaniak presented four works inside a semi-cylindrical tent, built out of PVC and plastic sheeting on a back lawn at 21st Place.

One of many stops in this year’s 2nd Floor Rear crawl, “Hot House” was a tidy and efficient display: poetry to a gallery’s lengthy prose. The temporary greenhouse was erected as part of a collaboration with the “Uptool” programming series, based out of UIC’s Greenhouse and Plant Research Laboratory. “Uptool” screens films, holds science demos, and gives lectures inside a more permanent greenhouse near Little Italy. The smaller-scale plastic frame in Pilsen served as a conceptual frame, gesturing at ideas of shelter or inhabitation. In passing into the half-opaque bubble, the visitor walked into the context helpful for understanding the objects on display.

This bubble was noticeably warmer than the outside air: Curt Miller had placed four terracotta space heaters in the corners of “Hot House.” Each heater was powered from underneath by a lit buddy burner, a stove made from smoldering cardboard coated with fuel and crammed in the butt of an aluminum beer can. The pots were hot to the touch, and gradually warmed the hand before singeing it.

A humble-looking, grade-school science project on a table at the tent’s center, “PF-TEK city no. 1” was a rock inside a sealed-up fish tank, humidified through a plastic tube that was connected to an adjacent, water-filled evaporator. On top of the rock a colony of yellowish-white mushrooms sprouted under the tank’s favorable conditions. The title of Szczepaniak’s piece references both a technique for indoor fungus cultivation (“PF-TEK”), and the tendency of modern artists to title their abstract works with non-descriptive numbers (“city no. 1”). By isolating the mushrooms and placing them on a pedestal, Szczepaniak highlights a case where nature appears to imitate art. But at a second, deeper level, “PF-TEK city no. 1” is a hot house inside of “Hot House.” Remove the fungus from its muggy home, and it will dry up in a matter of hours.

An untitled piece by Julia Klein helped to draw together the artificially biological feeling of “Hot House.” Klein suspended a floor-to-ceiling wire net from one of the greenhouse’s PVC support struts. She tied tufts of Spanish moss and bits of other multicolored detritus to the looped weave. The whole apparatus swayed gently with the passage of air through the plastic tent. The thick-leaved clippings felt parasitic, or spore-like, clinging to the net in a colorfully counterproductive way. Their occasional tremors heightened the sense that the greenhouse was alive, even though nothing had been planted inside.

“Hot House” turned the botanical conservatory into conceptual art in a deft and modest way. In a way, it symbolized the kind of “flash formalism” encouraged by 2nd Floor Rear at large. “Hot House” captured the wandering spirit of this backdoor expo, offering the visitor an installation that was equal parts swift, small, and smart.

Don’t Tell Me I’m Pretty

by Michelle Gan

This year’s 2nd Floor Rear installments centered on the concept of “being somewhere.” It seems fitting then, that the textile-centered exhibit in Avondale would be housed in the second-floor gallery space of the Hairpin Arts Center, a building impossible to miss on account of its massive, glowing sign.

Curated by poet Elizabeth Lalley and Lauren Leving, a UIC grad student, “Don’t Tell Me I’m Pretty” showcases the work of photographer and textile artist Na Chainkua Reindorf and fiber artist Grace Kubilius, alongside fellow textile artist Grace Cross and mixed media painter Sherwin Ovid. Their creations––mannequins dressed in loud outfits including a floor-length hot pink dress, bouncy exercise balls encased in colorful patterns of woven fiber, and a seemingly blood-soaked hammock––vivify the white walls and floors of the gallery space.

The range of visitors and gallery organizers present amplified the sense of animation. A girl in black lipstick who had manipulated a clear garbage bag into a jacket, complete with hood and shorts, conversed with a woman wrapped in a bright green Ghanaian dress that almost looked like it was lifted off of one of Na Chainkua Reindorf’s mannequins. A four-year-old child and his sister bounced on the textile exercise balls as their mother chatted away to a friend, competing to see who can bounce higher.

By the entrance, there were tables occupied by 2nd Floor Rear organizers; one invited passersby to play a tarot card game. “People just want to promote creative practices, we’re all about that,” said Jesus Gonzalez Flores, one of this year’s associate curators, “We just present a platform for them.” Flores noted that many involved with “Don’t Tell Me I’m Pretty” are currently pursuing an MFA, and that the host gallery is not corporate, meaning that all proceeds go entirely to the artist.

In her response to the overall theme of “We Are Here,” Na Chainkua Reindorf took a global point of view. She showcased six textile dresses—on mannequins and in photographs—that represent six of the eight Millennium Development Goals, international development goals for developing countries set by the United Nations.

One photograph depicts a woman in an African print dress with hues of red, orange, and yellow, looking skyward in a barren field. The stark contrast between the crops on the pattern of the dress and the dead fields in which the model stands seems to refer to the UN’s goal of eradicating extreme poverty and hunger.

Reindorf honed in on Ghana, a developing country where clothing is an important indicator of status and occasion. Explaining her rationale for exploring the Millennium Development Goals as they pertain to Ghana, Reindorf said, “Ghana’s progress, in terms of reaching some of these national developmental goals, has not been fully realized.”

“Don’t Tell Me I’m Pretty” challenges viewers to look past first impressions of elegant women in beautiful dresses, or of cute, bouncy playthings, and instead encourages us to look past reactions to aesthetic and to explore what each component may mean.

Na Chainkua Reindorf’s MDGS: A Fabrication Study can be seen at ncreindorf.com/mdgs-a-fabric-study