Just a block south of the 63rd and Cottage Grove Green Line, on the northeast corner of the intersection, sits a squat two-story building. Its facade of light stone is punctuated by decorative maroon bricks and sets of three arched windows framed with golden wood. Though not imposing, the building quietly calls attention to itself with its combination of textures and mesmerizing repetition of small shapes. It begs the viewer to stand and consider it, or perhaps to run a hand over the curls of the putti in its carved stone molding.

This is the Grand Ballroom, previously known as the Frank Loeffler Building. In November 1923, Loeffler purchased the lot’s previous building, a double storefront with tenements in the rear, from the notoriously corrupt former-mayor William Hale “Big Bill” Thompson for $150,000. Loeffler had that building demolished and constructed the Frank Loeffler Building, the two-story Renaissance Revival structure that remains there. Its current occupants include JB One, a carry-out restaurant; Teazze Salon; and the office of 20th Ward Alderman Willie Cochran.

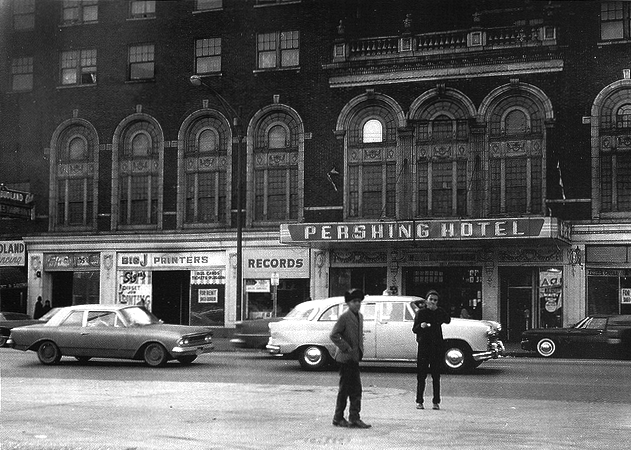

In the Jazz Age years after it was built, the Loeffler Building was neighbored by the 3,200-seat Tivoli Theatre movie palace and the seven-story Pershing Hotel. The Loeffler, in its heyday, was home to the largest beauty parlor in Chicago and the Chinese-owned Cinderella Cafe, a thousand-seat space whose central feature was an enormous crystal slipper suspended from the ceiling above the dance floor.

As Chicago’s Black Belt expanded in the 1940s, white residents moved out of this pocket of Woodlawn, and its hotels and ballrooms began their second lives as hubs of the South Side’s African-American jazz and social scenes. The Loeffler Building became known as the Grand Ballroom, and hosted lavish pageants, dances, and fundraisers for sit-in protests. The Pershing Hotel became black-owned in 1943, and would go on to host countless artists, including Earl Hines, Ahmad Jamal, and Charlie Parker, in its ballroom through the 1950s and 1960s.

Before that, however, the Pershing was the site of a bitter conflict over issues of housing and segregation during World War II. The U.S. Army had planned for a number of redistribution centers for returning overseas veterans. Under this program, dozens of hotels and other buildings across the country were vacated in order to provide temporary housing for soldiers returning from abroad. The soldiers were to be given the opportunity to rest for a few weeks, sometimes in the company of their wives, before returning to combat.

African-American community leaders denounced the plans to seize the Pershing on several grounds. In October 1944, the Chicago Defender reported that the Army intended to keep the centers segregated, which community leaders decried as a Jim Crow program that would almost certainly lead to inferior care and amenities for African-American veterans. Some objected to the repurposing of the Pershing at all, in light of “a critical civilian housing need” that the building met as a residential hotel. This concern highlights the hardship of housing scarcity that plagued the city’s African-American community in the era when racially restrictive covenants still limited the areas in which they could live.

An all-star delegation of leaders— Walter White, secretary of the NAACP; Channing Tobias, secretary of Negro work for the YMCA; and Mary McLeod Bethune, president of the National Council of Negro Women—expressed their opposition in an in-person meeting with President Roosevelt. While the Army did initially seize the hotel, they soon abandoned the plan, and the African-American troops left after a single month. The local community celebrated this change of plans as a victory over Jim Crow.

By the mid-1960s, the Pershing had undergone countless changes in ownership (writer Lorraine Hansberry and her family owned it briefly in the early 1960s) and was falling into disrepair. In 1974, the Defender called it “an eyesore in the Woodlawn community.” The Pershing Hotel was demolished in the 1980s and remains an overgrown vacant lot. The Tivoli Theatre closed in the mid-1960s and a Family Dollar store now occupies the site.

The Grand Ballroom is now the lone indication of 64th and Cottage Grove’s Jazz Age history. It has seen the fortunes of the neighborhood rise and fall around it, and its own fortunes experienced an upturn in 2003, when developer Andy Schcolnik acquired the building. He began a restoration project in partnership with now-defunct ShoreBank, a community-development bank established in the 1970s to fight racist redlining practices on the South Side. The Ballroom is now fully restored and open as a concert hall and private event space, according to its website. Comparing the fates of the Pershing and the Grand Ballroom is a reminder of the fragile contingencies of historical preservation. While we might like to think otherwise, the distance between pristine restoration and the wrecking ball is often nothing more than a question of which gets there first.

The Washington Park National Bank building, across the street from the ballroom, is another historic and disappearing Woodlawn edifice that begs for adaptive reuse. It has a meandering history that includes being founded by a major-league baseball player and the wake of Clarence Darrow.

Woodlawn’s nightlife attractions, established at the outset of the 1893 Fair building boom, later operated in plain violation of the Volstead Act, including dozens of taverns and gambling halls on Cottage Grove such as Gypsy Lane or the Southland Club.

At 68th & Cottage Grove was the Granada Cafe, a brothel/gambling den/cabaret which played host to Guy Lombardo’s group and which was the site of a gangland shooting which was broadcast over the radio during a live performance.

When the Granada mysteriously burned down, owner/wiseguy Al Quodbach leased the Cinderella Cafe and renamed it the New Granada.

The Pershing Hotel was founded by two vaudevillians who ran a dance hall at 61st & Cottage and a bootlegger who worked with Al Capone – his South Side operation included a headquarters which was the entire top floor of the hotel.

Is the Ward Office for an Alderman located there, or nearby?

Great Historic Information!

Tear the Grand Ball Room down. We, the African American people, need to rebuild. We need housing. Tear the ballroom down. The neighborhood is drug infested, crime infested and infested all around the board. Tear the property down so the black community can rebuild. The Grand Ballroom building is not doing the black community any good at all. The only thing that should be left standing is the green line, the social security building and the public aid office. Send the wrecking ball crew in. Begin tearing down south of 63rd street on Cottage Grove. I am standing on this on. Just run the wrecking ball through. We need housing. I am walking in Thurgood Marshall’s shoes. Whites don’t come in the neighborhood anyway. Blacks were not even allow in the community when whites were going to the Grand Ballroom. Tear it down. Then maybe the African American Community can raise their standards.

My grandmother owned a salon “Selena’s House of Beauty” in both the Mansfield and Pershing Hotels at the same time during the height of the civil rights movement. I wrote about it in my award winning book “With These Hands; A Country Girl Came To Town” Before moving to 63rd & Cottage and opening the first 24 hours salon. She then became the first Black woman to open a Beauty & Hair Weev salon in Chicago’s Loop in the Stephens building 17 N. State Street that Great Street!

My father had a used furniture store at 6454 Cottage Grove. As a kid I saw many black celebrities coming and going at the Pershing…Joe Lewis, Lena Horne and many others.

In the 1920’s my grandfather and family including my mother Lily Mark Tolpo lived at 7634 S. Cottage Grove Ave. Sing Hong Mark would walk the 12 blocks to the Cinderella Cafe where he and other Chinese men had borrowed money from Al Capone and opened the Cinderella Cafe. There my mother would pass out party favors as a young child. Music by the Century Serenaders Orchestra and the Frankie McMasters Orchestra would fill the ballroom with sound. Later in the late 1930’s Lily would perform with the Hollywood Cowgirls featuring Dot Hackley.

Why is my comment shown under Bob O’ Malley’s name?

Was there a grocery store in the 60’s located where the Family Dollar is on Cottage Grove called Del Rey Foods.

I think it was black owned.

Thank you for this article. I live on 57th and Kimbark and often go running south on Cottage Grove. Listening to Ahmad Jamal and seeing the album at the Pershing got me to look up the hotel.

So sad to learn about the fate of such a historic building glorified in the Jazz Age. Still nice to know a portion of the structure is still left for memory’s sake.

I remember the Pershing Hotel from living close to it’s location in Woodlawn. Walked past it all the time as a pre-teen and then as a teen/young adult by frequenting the Budland Dance Club located in the lower level of the hotel. I still have the now collectors item 33-1/3 LP record Ahmad At The Pershing…..Good memories.

Me too!

Great article. I remember a barber shop or hair salon from my youth (in the Sixties) named “House of Nelson.” It was home of some serious “processes” (or “conk jobs”) and was even featured in a booklet inserted in the original packaging of the Muddy Waters “Electric Mud” album. I seem to remember House of Nelson being located across the street from the Tivoli but it might have also been across from the Regal. I just remember seeing a lot of “players” and musicians there and it was always a bustling atmosphere.

Anyone have any historical info about that place? And where was it located?

I got a process at House of Nelson my sophomore year of high school. Josephine was the woman conking women. It was my mother’s idea for me to be the Guinea pig. I recall it being in across the street from the Tivoli. I was cute for a hot minute then my hair leapt from my scalp. It didn’t fall out, it leapt! Josephine felt terrible about it so she gave me a wig. Fabulous wig way before anyone – especially a teenager — was wearing them. I eventually got the nerve to toss the wig and be the 1st Afro at Harlan High School.

Hello. Does anyone remembers the name of the hotel/motel that used to be on 201 E 63rd Street, long time ago?

I remember going to Budland every Saturday and Sunday. What ever happened to a young man by the name of Tony that spin records sometime at budland