“The water quality, it’s kind of weird. But we’re local people who were raised next to steel mills. It’s been normalized to us,” said East Side native Peter Matushek as he prepared to surf at Whihala Beach in nearby Whiting, a city just across the state line, tucked up against U.S. Steel’s finishing facility.

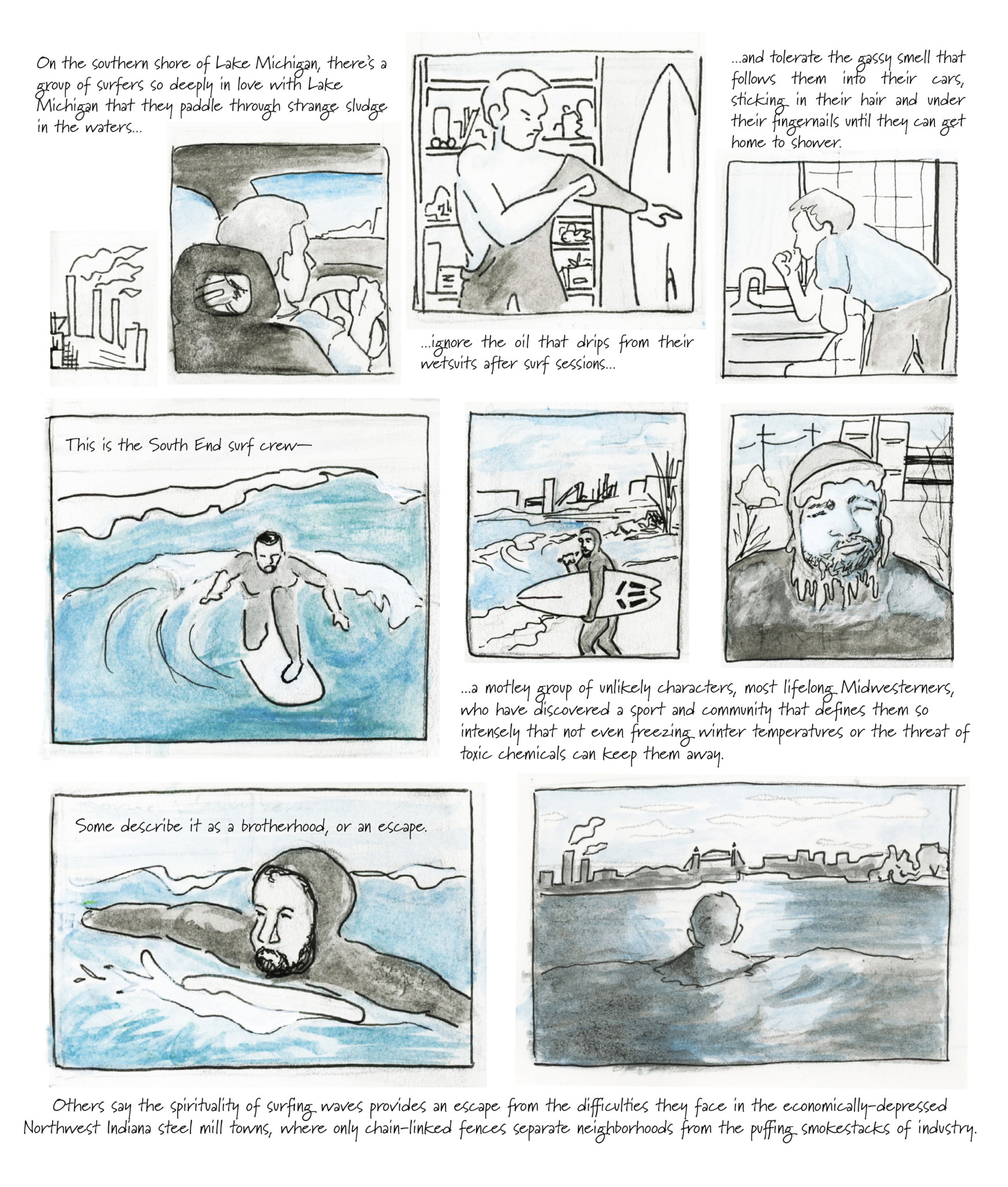

Most of these “South Enders” grew up under the shadow of steel mills and many rely on stable industry salaries to support their families.

They surf in winter conditions and battle gale-force winds, but the real obstacle they face is the pollution. Nearly everyone has a story about a hospital visit after a surf day, a urinary tract infection, kidney issue, ear or eye infection, or rash.

After one surf session two years ago, Matushek spent an entire week in the hospital. He had a kidney infection, and it took three months before he could surf again. After storms, which tend to push dirty runoff from nearby roads and factories into the lake, Matushek checks the newspaper for water quality alerts, but his passion for surfing usually trumps fear of illness or infection. He and his buddies log three to four surf days per week, especially in winter.

“My entire life someone would say watch out for this or this cause you’re going to get cancer. Don’t eat hot dogs every day because you’re going to get cancer,” Matushek said. “I’m like, I grew up next to mills, man. I’ve been breathing this stuff my entire life. If I’m going to get it, I’m going to get it.”

But in April 2017, U.S. Steel facilities spilled hundreds of gallons of toxic waste into Matushek’s backyard playground, closing beaches and drinking water inputs. The Clean Water Act violations prompted a major lawsuit by the Chicago chapter of the Surfrider Foundation, an environmental nonprofit focused on protecting the world’s oceans, waves, and beaches. Soon afterward, the City of Chicago filed its own lawsuit, which was eventually combined with the Surfrider suit.

Federal and Indiana state regulators also took action, and this April, released a proposed consent decree as part of a settlement, which includes requiring U.S. Steel to pay $900,000 in fines to the National Park Service, EPA, and other agencies involved in the cleanup. It also, if approved by a federal judge, will require U.S. Steel to implement better spill notification practices to these agencies and the public, to repair facility infrastructure to prevent further spills, and to conduct daily monitoring.

But this plan falls short of what the environmentalists and lawyers view as necessary measures to protect public recreation and drinking water from another spill.

It’s easy for to Chicagoans to miss what happens across the state border in the industrial Northwest Indiana region. But pollution doesn’t observe state borders. For hundreds of years, those who have claimed the lake’s 1,640 miles of shoreline as their homes have pulled natural resources like iron ore, coal, and limestone from its basin; drunk its water; and harvested its fish. In the reverse, runoff from agriculture, sewage from Chicago’s bulging population, and trash has found its way into Lake Michigan.

Today ten million people drink Lake Michigan water, including every resident of Chicago. The city’s water purification process is powerful and can filter most pollutants from the water. But it’s difficult to be sure that every last trace of a known carcinogen like hexavalent chromium—the main pollutant in recent spills—has been completely removed.

Surfing on the South End of Lake Michigan is a far cry from the rolling waves of places like sun-drenched Venice, California.

For one, there’s the season. Winter is the best time for waves on the South End of the lake, when the area benefits from more than 300 miles of open water to its north, a runway that provides south-blowing winds with enough space and depth to build powerful waves and where water temperatures dip to thirty-two degrees, even freezing in parts.

“It only calls the people who really want to do it,” Matushek said. “I think the lighthearted surfers, it’s just not for them.”

Roger Coppinger of Porter, Indiana has surfed in Lake Michigan since the late 1980s, making lifelong friends who structure work and family obligations so they can surf when the waves crash right. But he’s also seen his share of the damage.

“You can just tell that there’s something in the water that shouldn’t be and that’s where you end up with infections,” Coppinger said of the area in Portage where the water tends to turn chocolatey brown after a rainstorm.

Coppinger talked about a time in the nineties when he was in and out of the doctor’s office with ear, eye, nose, and throat infections so often that his doctor told him to take a break from the water.

“When you’re surfing it’s kind of hard to keep your mouth closed and not get any water in your mouth,” he said.

“I put in some ear plugs to chase the ear infections away, and I deal with the rest,” he said. “Being in the water is the only thing that I would do to prompt any of that stuff.”

In Chicago, Surfrider members were tired of hearing about surfers getting sick. So in 2016, its Chicago area chair Mitch McNeil and member Judith Miller started gathering information on industrial pollution near their surf spots. They wanted to better understand whether industry was breaking the law and the kinds of penalties and fines they faced for polluting. They called it the South End Water Quality Campaign.

“We didn’t really have any grand designs on reforming the system. It just seemed too immense and intimidating,” McNeil said. “We wanted to educate the surfers, let them know what was in the water.”

Meanwhile, the South End surf crew was growing. More and more locals began to gather, learning through word of mouth and at the St. Joseph, Michigan-based Third Coast Surf Shop about the best places to surf, the weather to track in anticipation of the best waves, and how to scrub hard, wear earplugs, and avoid illness.

The group’s favorite surf spots span from the industrial cities of Whiting, East Chicago, Portage and Gary, Indiana to the more upscale vacation town of New Buffalo, Michigan. The waves break cleanly on the South End, and at some beaches, decrepit piers from industrial shipping blocked the east-west winds, creating protected alleys that kept the water smooth on stormy days.

Then on April 11, 2017, a Portage U.S. Steel facility spilled 350 pounds of chromium—including 300 pounds of toxic hexavalent chromium—into Burns Waterway, an industrial ditch just one hundred yards from Lake Michigan and a common dumping site for other industrial waste and local sewage.

Hexavalent chromium, or chromium six, is the toxic, man-made version of the chromium that occurs in nature and is classified as an essential nutrient. It is proven to cause lung cancer and skin rashes, with possible links to infertility and liver and kidney disorders. It is a common byproduct of industrial processes and is used to prevent metal from rusting, or to preserve leather and wood. At its finishing plant, U.S. Steel uses chromium in the manufacturing of tin and steel for use in cars, construction, industrial containers, and electrical materials.

After the spill, authorities closed beaches around the Indiana Dunes, and the town of Ogden Dunes shut down the flow of drinking water serving residents near the lake. Three days later, EPA testing revealed no major risk, so the town turned the water back on and the surfers got back in the water. But then, in October, U.S. Steel spilled again, this time dumping 56.7 pounds of chromium in one day. But, unlike with its previous spill, it didn’t test to find out how much of the spill was the toxic hexavalent variety, according to a report by an inspector with the Indiana Department of Environmental Management.

The spills prompted the Surfrider Foundation to speed up its existing water quality surveillance project, and begin proceedings for a lawsuit. Rob Weinstock, an attorney with the University of Chicago Law School’s Abrams Environmental Law Clinic representing the Surfrider Foundation, was concerned with both the April spill but also the less-reported October 2017 spill, which he said could have prompted all sorts of other response actions had it been tested as toxic. “We’ll never know how much was toxic chromium. It could have been all 56.7 pounds,” he said.

The lawsuit, and subsequent inquiries undertaken with the law clinic, uncovered a history of gas and chemical dumping longer and more extensive than they had imagined. In its research, the group found numerous clear violations of the Clean Water Act dating back to January 2011.

Beyond the violations of U.S. Steel’s pollutant discharge permit, there’s still plenty of legal dumping. Every mill has permits that allow them to dump certain amounts of certain chemicals. How the EPA sets these limits and what they mean for human health is a murky issue, one that Surfrider hopes to change.

What Weinstock also found disturbing was a lack of maintenance records for the facility.

“They were operating this facility like it was a lawnmower in your garage,” he said. “But even with a lawnmower you change the oil. That is really troubling.”

Meanwhile at the Indiana beaches, Matushek and his surf brotherhood has kept surfing. The winter was a windy one and winds from the north piled up, slamming themselves into the icy barrier along the South End.

I don’t want surfing taken away from me,” Matushek said. “I’m going to do what I want and surf when the waves come. And if shedding more light on this brings about the fact that beaches will be shut down because these companies spill, that will suck.”

The Chicago-based environmentalists want to protect coastlines, beaches and the health of the people who enjoy them. South End surfers want the same, but not if it costs them surf days. They’re asking for more both transparency from industry and regulators—state and local authorities have long capitulated to the whims and needs of industry in Northwest Indiana—and faster cleanup times when spills happen.

But many Chicagoans have began to limit their time in South End waters. Instead they opted for the lesser surf at Chicago beaches. Some said that the risk of illness didn’t seem worth it for a few waves.

“It’s bad. My wetsuit, my surfboard, my hair. All smell like gas,” said Humboldt Park resident Amanda Bye. “I value my health more than a good wave.”

Bye stopped surfing in the South End after reading news of the spill. She described the strangely warm water and little flecks of black, indicators that something wasn’t right.

McNeil grew up swimming and surfing in Lake Michigan, but said he has to “rearrange his thinking” when he surfs on the South End. “Two times I didn’t shower just after. And I broke out in a rash that resembled hives,” he said.

Surfers like Bye and McNeil have the advantage of mobility and location. From downtown Chicago, it takes about an hour to drive to South End surf spots. Bye now drives two hours north to Sheboygan, Wisconsin, known in surf documentaries as “The Malibu of the Midwest” for its peninsula-like geography, which creates optimal surf conditions regardless of which way the wind blows.

This past Superbowl Sunday, a group of six surfed through a windy snowstorm before gathering with families for the big game.

Frozen chunks of ice floated in the thirty-three-degree water, moving in time with the rhythm of the swell. After a wave broke, it left behind a heaping pile of dirty ice chunks, a slushy barrier between land and water.

Matushek pulled his wetsuit hood over his ears and ran down the icy steps to the beach. He only slowed to step gingerly across piles of ice at the water’s edge, his foot occasionally breaking through and splashing into the water. In one smooth motion, he lay on his board, bare hands scooping water as he paddled out past the white water. Finally, he pivoted on his surfboard to face the shore.

Minutes later, with the flick of his wrist and a few powerful strokes, he moved into a wave, one, two, three more strokes and he was standing, board and body sliding down the front of a blue-gray wall of water. For a minute, it looked like he might fall. Then his knees bent and body relaxed as the wave took over. It propelled him forward with a surge of energy. Icicles coated his beard and wind sent whitecaps across near-freezing water.

“Surfing is the best. It just clears everything. It clears your mind. You’re allowed to just not think for a few hours of your life,” he said.

In anticipation of the proposed consent decree’s release, the Surfrider Foundation and city had temporarily paused their lawsuit in April to see if its remedies would be strong enough. As it happens, they were not, and according to Weinstock, the plaintiffs are going back before a magistrate judge this week to continue arguing their case. Separately, in comments submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice’s Environment and Natural Resources Division, which is responsible for the consent decree, the Surfrider Foundation and law clinic write that its proposed penalties are “insufficient” and “[fail] to vindicate the public interest.”

Among the allegations made in its comment are that future illegal discharges would not be prevented by the repairs required by the decree; the financial penalty is too small to deter other industrial facilities from illegally polluting waterways; and that the process by which the consent decree was created was rushed and did not contain sufficient community or public input. If the DOJ declines to amend the consent decree, the foundation and law clinic write, they will attempt to directly intervene with the federal judge overseeing its potential implementation. Left unsaid is that U.S. Steel is just one of many industrial facilities polluting waterways that lead to Lake Michigan—including BP’s Whiting refinery, which regularly pollutes with impunity, as it is rarely if ever disciplined by Indiana regulators, even when violations are found.

As summer continues, the lake water is warming up. Schoolchildren enjoy their weeks of freedom beyond the classroom and Whihala Beach lifeguards oversee the thousands of visitors who play in their sand and swim in their waters this summer.

The waves don’t build as high this time of year, and often surfers wait days or even weeks between surf sessions. But this year a lack of surf is the least of their concerns.

Sam Stecklow contributed reporting

Rebecca Fanning is a contributor to the Weekly. She recently received her masters from the Medill School of Journalism, and has volunteered for the Surfrider Foundation in the past. This is her first article for the Weekly.

Katie Hill is an illustrator for the Weekly and sometimes the Chicago Maroon, newly branching out into comics. She’s also worked with SkyART in South Chicago and currently works in the archives division at WBEZ.

Here is a link to the real story of these people you are depicting. Please feel free to share it!

https://vimeo.com/224848916