Sylvester and Felicia Toliver heard about it from a friend. Catherine Williams found out from her sister. Lolita Taylor’s cousin called her to tell her about it. On a sunny Tuesday morning in May, they and scores of other Chicagoans—bus drivers and day care operators and home health care workers and custodians and retirees—waited on foot and in their cars for a pop-up food pantry staged by the Greater Chicago Food Depository (GCFD). For many, this was the first time that they’ve ever waited in line for supplemental food.

As they waited, volunteers from local churches and the Greater Auburn Gresham Development Corporation hustled around the parking lot of a closed Save-A-Lot at 79th and Halsted, stacking boxes of produce and dry goods on folding tables. A video truck screened slides depicting proper handwashing and social distancing techniques, as well as graphics showing the most recent breakdown of COVID-19 deaths in Chicago by race. The Black and Latinx communities have been hit disproportionately hard, and Auburn Gresham has one of the highest per capita death rates in the city. Over the PA, Bill Withers crooned “Lean on Me.”

“Are you here for food?” a volunteer asked a passing pedestrian, then pointed her down 80th Street to the end of the line.

Scenes like this played out all over town in May as the GCFD, the food bank serving Cook County, launched a series of pop-up pantries in South and West Side neighborhoods—not just Auburn Gresham but in South Shore, Roseland, Little Village, Austin, and elsewhere, including Guaranteed Rate Field, aka Sox Park, in Bridgeport.

These and other predominantly Black and Latinx neighborhoods were already food insecure before the pandemic, said Nicole Robinson, the GCFD vice president for community impact. “There’s a large group of folks [on] the South and West sides of the city who have had a history of structural challenges related to double-digit unemployment, housing, and racial segregation that has made living a full healthy life—which includes access to nutritious food—more difficult.”

Now, need is skyrocketing.

In April, food insecurity doubled nationwide, and tripled among households with children compared to the predicted rates for March, according to a Northwestern University survey. A third of white respondents with children said they struggled with food insecurity, but about forty percent of both Latinx and Black respondents with children reported issues with food running out and not having enough resources to purchase more. In the Chicago metropolitan area, food insecurity rates rose to twenty-four percent.

A widely circulating news item in early April reported that in Texas, 10,000 cars had lined up at the San Antonio Food Bank’s pop-up distribution site in one day. Such dystopian scenes have yet to arise in Chicago, but at the Auburn Gresham pop-up the line of cars waiting at 10am stretched three blocks to the west.

“What we needed to do is pop up and bring the community something that they could do to address their immediate needs now,” said Robinson. “We have a lot of folks who are temporarily furloughed, newly unemployed, and maybe are not familiar with our traditional pantry network, which might be in a church basement or at a community center. And if they’re not connected, they don’t know where to go.”

Operations like the GCFD have an outsize footprint in the landscape of hunger relief, which makes them uniquely able to scale up in times of crisis. But even before the pandemic, the disparate distribution of resources between Chicago’s North and South Side pantries made it clear that scale alone is not enough to meet ever-increasing need. And a number of heavily Latinx neighborhoods on the Northwest and Southwest sides of the city have relatively few food pantries, even as that population is hard-hit by the pandemic and resulting economic impacts.

With the pandemic’s significant impact on both the food supply chain and individual food security, the consequences for hunger relief organizations across the country are expected to be dire. Demand for supplemental food is likely to map across all-too-predictable lines of race and class. In June 2020, shortly after the food pantry pop-ups started, the GCFD released an interactive map that outlines disparity in the city and their “racial equity” strategy to address inequality in the times of COVID-19. But why did it take so long?

In Chicago, under normal circumstances, the GCFD doesn’t distribute food directly to residents. Instead, it works with a network of more than 700 food pantries, shelters, kitchens, churches, and other organizations across Cook County. These organizations purchase dry goods and meats, dairy, and produce at reduced rates from the Food Depository, which operates a 280,000-square-foot warehouse near Interstate 55; the organization estimates that it moves 200,000 pounds of food a day.

In 2019, the GCFD announced plans to build an adjacent 40,000-square-foot new facility to house a meal-preparation kitchen and culinary training center, designed to meet the anticipated spike in demand for supplemental food assistance as baby boomers age.

Now, due to the pandemic, plans for the new facility are delayed. The Trump administration’s proposed cuts to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) eligibility, which would have forced an estimated 50,000 people in Cook County to lose benefits, are also temporarily delayed, but the nonprofit network Feeding America predicts an additional 17.1 million people nationally will seek food assistance in the next six months. And since the implementation of the statewide stay-at-home order on March 20, about thirty percent of the GCFD’s network pantries have closed, some permanently.

Neighborhood pantries that remain open have scrambled to adapt. They’ve instituted mandatory masking and social distancing practices, and placed restrictions on volunteer capacity. Before the pandemic, said Nicole Robinson, the GCFD was working to implement strategies that had the hypothetical (if improbable) goal of rendering the Food Depository obsolete—strategies like getting families enrolled in SNAP, which can provide “twelve times” more food than a trip to a pantry, and is connected to earned income tax credits. The planned Chicago’s Community Kitchen meal prep facility would also provide workforce development for people in communities burdened by high unemployment.

“We were using the food as a connection point to actually get people to work, to get people connected to benefits that they were entitled to, that would make it less stressful so we could actually shorten the pantry line,” she said. “We never celebrated having long lines at a pantry. We wanted that line to be shorter and really keep people out of the line. … Unfortunately, we’re in a situation now where we’ve taken a few steps back.”

History and Disparity

Food banks and food pantries are a relatively recent invention; the first food bank in the country opened in 1967 in Phoenix, Arizona, but the concept didn’t really take off until the early 1980s, thanks to the Reagan administration’s drastic cuts to social safety net programs. As Andrew Fisher points out in his book Big Hunger, in 1979, there were thirteen food banks in the United States. In 1989, there were 180. In the past decade, since the economic crisis of 2008, food banks have doubled their distribution; nationwide, they now distribute 5.25 billion pounds and serve 40 million people a year.

In Chicago, the number of food pantries increased by around sixty-three percent from June 2018 to June 2019. But with one-third of the 700 or so pantries in the Food Depository’s network, temporarily or permanently closed since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, small pantries, with fewer resources, are finding themselves going the extra mile to meet a growing constellation of needs.

Since Chicago’s food pantries are privately run, many of them by churches, there is no underlying system to ensure equity or make sure that all neighborhoods are adequately served. Some lower-income neighborhoods with much need, like Uptown on the North Side, Humboldt Park on the West Side and Roseland on the South Side, have a relatively high number of pantries, according to data from IRS filings analyzed by South Side Weekly. Other swaths of the city have few, including the sprawling Southeast Side; the Southwest Side corridor of neighborhoods like Brighton Park, McKinley Park, Little Village, Gage Park, and Archer Heights; and Northwest Side neighborhoods including Avondale, Albany Park, and Hermosa. All these regions are home to many working-class Latinx immigrant communities, a population that now has the state’s highest number of COVID-19 cases. The disparity in pantry distribution has persisted even as more pantries have opened in the past couple years.

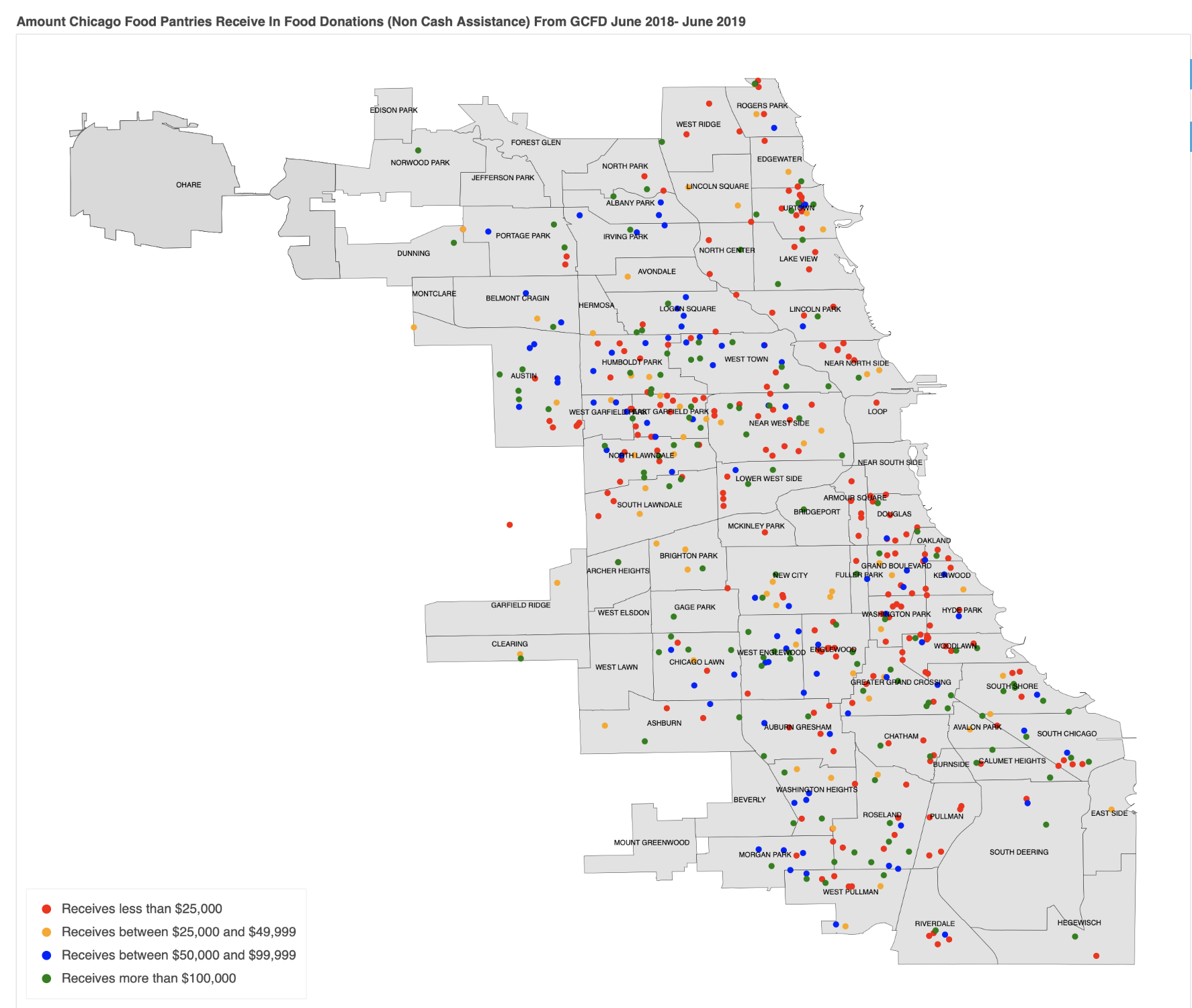

In addition to the food that the Greater Chicago Food Depository sells at reduced cost to pantries, the depository also donates food to the pantries. IRS filings show the amount of food donated as “non-cash assistance.”

South Side Weekly examined the Greater Chicago Food Depository’s 2018–2019 Form 990 IRS filings to retrieve information on all organizations in Chicago receiving more than $5,000 in non-cash assistance, and displayed the information on the (below) map.

In 2018–2019, according to the document, Greater Chicago Food Depository provided non-cash assistance to 499 organizations, predominantly food pantries, in Chicago. Out of the 499 organizations, 113 received more than $100,000 of non-cash assistance; 89 got between $50,000 and $100,000; 60 got $25,000 to $50,000 and 217 got between $5,000 and $25,000. The Greater Chicago Food Depository does not list organizations that receive less than $5,000.

GCFD spokesperson Greg Trotter noted that “the amount of food that a partner receives depends on numerous factors, including their capacity, frequency of distribution, the number of people they serve and how much they choose to order.” Many of the red dots, he notes, are also children’s meal programs, which are typically smaller in scale than a large food pantry.

Still, Rebecca Sumner Burgos, the community engagement coordinator at La Casa Norte, a food pantry and social service organization working in Humboldt Park and Back of the Yards, observed that when she uses the “find food” function on the GCFD website, there are many providers in some neighborhoods and very few in others, especially in parts of the West and South Sides. For example, the finder lists just two pantries in South Shore, but seven in Logan Square, where the median income is $75,333 compared to South Shore’s $28,890.

And even in the neighborhoods that appear in the data to be well served by food pantries, supplies may not be enough to meet demand, and access can be difficult for families who struggle to get transportation or risk facing violence when they venture out. These barriers are only heightened by the pandemic, when traveling on public transportation has become highly risky for people especially vulnerable to the disease, and neighbors or family members may be less able to help out because they have kids at home or their own health concerns.

A network of neighborhood-based mutual aid groups has sprung up to help provide food to needy people during the pandemic and community groups like Teamwork Englewood and R.A.G.E. (Resident Association of Greater Englewood), and many others, are adding food provision and delivery to the host of services they already offered on a shoestring budget. In the aftermath of the late-May protests against police violence and racial injustice, when the threat of looting and vandalism temporarily closed the few existing South Side grocery stores, banks, and other businesses, grassroots food distribution efforts saw another strong surge, many of them led by young Black and brown activists. But it’s still unclear how such efforts may be maintained over the long term, and whether they can possibly be enough to meet the vast and increasing need in struggling neighborhoods.

Challenges

With the disparate distribution of resources well documented, it’s worth asking why closing the gap appears to be such an intractable problem.

For some organizations, simply having space to operate is a hurdle, as are the requirements and paperwork of setting the group up as a nonprofit—a requirement to participate in the GCFD’s network. That’s why so many pantries operate under the existing nonprofit umbrella of churches or faith-based organizations, said Ryan Maia, an AmeriCorps volunteer at La Casa Norte researching “food as medicine,” the increasingly prominent idea that making sure people have affordable and healthy food will improve their health outcomes.

In those instances, “the organization itself already exists,” Maia said. “But if you’re trying to create something new in an area that doesn’t have emergency food providers, where are you going to get the money for that? Who’s going to just give you a check for $100,000?”

Pantries operating out of church basements and kitchens may have more flexibility and less bureaucracy than the nonprofits that are part of the GCFD network, but with sparse resources and aging buildings, they often struggle to serve their communities. They might only be open on weekends, or just not have the resources or capacity to run a robust program. South Side Weekly’s analysis showed that out of 499 food pantries listed in Chicago in 2019, more than 170—over a third—were run out of churches.

For example, at Our Lady of Guadalupe church on the Southeast Side, a few volunteers stock nonperishable food, clothes and other emergency supplies in a small room to help the elderly and low-income residents of the once-thriving community that has struggled economically since steel mills shut down decades ago. Working with allies in a coalition called the South Chicago Food Network, they try to reach people who may be homebound, skeptical or suspicious of aid efforts, and not accustomed to getting or cooking healthy, fresh food. The goal is to help residents not only with food but with connections to housing, immigration, and mental health services. At a meeting in the church basement in the early days of the pandemic, a handful of women ate yogurt, blueberries, and granola bars while reminiscing about a successful health fair they ran last year, strategizing about reaching residents, and lamenting the plight of people unable to travel to stores in other communities or Indiana, even if they did have the money to spend on groceries. The food pantry is not connected with the GCFD, so they rely almost entirely on private donations. While they are grateful, it is not always ideal.

“[Donors] give you garbanzo beans, cases for months, so people don’t want garbanzo beans anymore,” said Vanessa Molina, a food pantry director with the church. “Connecting people with resources at pantries is a good move because people don’t know what’s out there. They’re real isolated, they don’t know who to ask.”

Molina noted that on July 15, St. Kevin Catholic Church on the Southeast Side held a food giveaway—including watermelon, cabbage, milk, and meat—but few residents showed up. “It’s on Facebook, but a lot of people don’t have Facebook,” said Molina, who with others at Our Lady of Guadalupe prints fliers listing food pantries in the area. “There’s stuff to be given, it’s just people are unaware. It’s word of mouth, and catch as catch can.”

Our Lady of Guadalupe closed its pantry for several months this spring; it just reopened in early July, handing boxes of food through a gate in the alley by the church. Other church-based pantries on the Southeast Side are in the process of figuring out how to safely reopen.

Meanwhile, the two-year-old Pilsen Food Pantry has stayed open throughout the pandemic, and even moved into the Holy Trinity Roman Croatian Parish church at 1850 S. Throop in the middle of the shutdown, maintaining hours of service five days a week. They’ve seen traffic spike as high as 260 families a week, but, said founder Dr. Evelyn Figueroa, things have currently stabilized at around 220 families and, “every day that there’s one of those pop-ups, if the alderman is hosting or a church is hosting, our numbers go down by about thirty families.”

Though people are not allowed inside the building to pick and choose their groceries as they once were, they are able to place an order with an intake worker, and then the order is filled by a volunteer working in the back.

“It’s like science at this point. It works really really well,” said Figueroa, noting that it was important to her to try to maintain the dignity of the experience.

What doesn’t work so well is the building, owned by the Archdiocese of Chicago, which has recently closed and merged several churches in Pilsen. “Taking care of these old buildings costs a lot of money,” pointed out Figueroa. “It’s a 110-year-old building. It doesn’t have an elevator; it’s not ADA accessible—we had to build a ramp. The boiler is broken, the windows are terrible.”

In the wake of the May 31 unrest following the killing of George Floyd, the pantry saw a surge in monetary donations. But it’s still not enough. Perhaps more crucially, they also saw a surge in volunteers—but figuring out how to harness that enthusiasm for the long term is a challenge.

“A lot of people were very motivated after the riots and signed up a month in advance, and when we check in with them then you get a cluster of cancellations the day before that makes it very difficult to manage,” said Figueroa. “It’s very hard. Because this is for the most vulnerable people, and it’s really only a three-hour shift, so it’s just very disappointing when people don’t understand that a food pantry operates through volunteers; we don’t have any money.”

Innovation and Expansion

The Greater Chicago Food Depository has been looking at ways to leverage technology to move the needle on food insecurity issues—even before the pandemic—and such innovations could be even more important now. In November 2019, the depository announced it had partnered with McKinsey, a management consulting firm, to create a tracking dashboard that would rank areas in terms of highest and lowest need, helping them decide which areas to prioritize.

Other initiatives have included the build-out of a chatbot that recommends nearby food resources in partnership with Here360, and a food optimization model, in collaboration with McKinsey, that helps manage the distribution of fresh produce.

The depository isn’t alone in trying to think innovatively about food security and distribution issues. In January, Burgos and Maia said they wanted to explore “food as medicine” partnerships with local hospitals and health services such as AMITA Health and Howard Brown Health. The services could refer patients to the La Casa Norte food pantry. In turn, La Casa Norte also hoped to implement a new referral service called NowPow, which would enable them to provide and track referrals to other community services such as shelter, health care and social services.

“Something that a lot of emergency food service providers struggle with is hunger is not the only thing that’s going on, right?” Burgos said. “It’s part of the constellation.”

In March 2019, La Casa Norte launched a new fresh food market in partnership with Lakeview Pantry, one of the city’s oldest food pantries, in an effort to serve a large swath of the city. The partnership came out of a five-year strategic plan built with Boston Consulting Group, a management consulting firm.

In 2019, Lakeview Pantry covered thirteen neighborhoods, served 9,000 unique clients and received $1.56 million total in-kind food donations from GCFD and stores including Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods.

Lakeview Pantry has developed a lucrative donor base—seventy-three percent of the pantry’s monetary donations come from individuals. Monetary donations from individuals and grants accounted for $2.5 million in revenue in 2019. Individual funding allows the pantry to be flexible and innovative in its models.

“We can be really creative,” said Jennie Hull, director of programs at Lakeview Pantry. “I think this area has blessed us. I mean we’ve been around fifty years. I think people know us, and we’ve gotten really lucky that we have so many individual donors.”

Over the years, Lakeview Pantry has rolled out new services including mental health counseling, home food delivery, career advisory sessions and pop-up pantries in long-term-care homes.

Meanwhile, the new 10,000-square-foot warehouse that Lakeview Pantry opened last year in Ravenswood, called The Hub, could be a model for pantries of the future. High tech and efficient—equipped with commercial food chillers and a kitchen with a luxury coffee machine—the warehouse allows Lakeview Pantry to serve people living in other neighborhoods through an online ordering system. People from anywhere in the city and suburbs can order food from The Hub, provided they are able to get there to pick it up, a potential challenge since it’s not easily accessible by public transportation.

“You can just go [online] and pick what you want and then just show up and get it,” Hull said. “If you go to our other locations, and it’s a busy day, you’re going to wait two to three hours.”

Since the pandemic started, restaurants and coffee shops like Starbucks have adopted a model where people order online and pick up their food, often in a “no-touch” system with little human contact to avoid transmitting the virus. This model could increasingly be an option for food pantries, like Lakeview Pantry, allowing them to more efficiently serve a wider range of clients, even during a pandemic lockdown.

While technology and innovation can help food pantries streamline their operations and increase efficiency, veterans of social service work know well that the interlocking challenges facing poor, vulnerable and marginalized communities don’t necessarily lend themselves well to an efficiency-based approach. It’s likely a matter of “all of the above,” where expanded, centralized, data-driven, and innovative food distribution programs are needed, but where at the same time there is no replacement for grassroots organizations or churches that are deeply embedded in their communities.

On the Ground With Client Choice

Back in late January, a hushed crowd filled the entrance and main room of Casa Catalina Basic Human Needs Center in Back of the Yards on a Wednesday afternoon. After being closed for three months for renovations, the pantry was reopening with a new “client choice” system for distributing food that allows people to “shop” for options much as they would in a grocery store—as a way to destigmatize the need for food assistance. Sprinkling holy water, Father Gerard Kelly, chaplain for Catholic Charities, blessed the space, “so that the good work here will continue,” he said.

Among its 10,000 unduplicated visitors a year, Casa Catalina serves a largely immigrant population, many of them undocumented. About a third of Back of the Yards residents are foreign-born, and a third of households in the community earn below the poverty line.

But even as the need for food has intensified across Chicago, Casa Catalina has seen a drop in participants, said Sharon Tillman, director of Family Support Services for Catholic Charities. Many clients fear even at the pantry they’ll be caught by the federal government’s stepped-up immigration enforcement, she explained.

“They may trust us, but how do they know what’s going to happen to them?” Tillman added.

Ironically, Casa Catalina spent three months revamping its space to launch the “client choice model” just before the pandemic forced it and food pantries across the city to abandon that process. The vibe on that opening day in January showed the important role that the pantry plays in the neighborhood, and the great need for its services.

Several supermarket-like aisles were stocked with canned goods, cereals, and other dry goods, along with several freezers of meat. After the prayer, clients filled the cluster of seats inside as a line formed down the block outside in the cold. One by one, the pantry’s volunteers—that day a mix of older nuns and neighbors, along with young college students—called the attendees’ numbers and proceeded to help them “shop” for food.

Darrell Price, waiting his turn, leaned against a shopping cart in tall diabetic boots with heavily padded soles. Receiving just $16 a month through his Illinois Link card, Price said he was looking forward to picking up some beef and other protein. Previously, he added, the prepacked bags the pantry used to hand out didn’t always suit his dietary needs, offering items made with additives, such as corn syrup, that he couldn’t eat.

“I’m diabetic,” Price said. “So now I can pick what I want, like fresh fruit and bread.”

Six months later, strolling the aisles chatting with volunteers and choosing food off shelves is a thing of the past. Groceries now come in prepacked boxes from the GCFD, and are distributed out the back door of the building to clients waiting in socially distanced lines in the alley.

The whole goal now is to reduce contact between volunteers and clients, and thus reduce the risk of spreading the coronavirus. Meanwhile, the center’s longstanding volunteer base has shrunk, and the number of workers (now mainly interns) allowed in the building at one time is strictly limited. With so few workers, “it’s been a struggle to get it all done,” said supervisor Sharon Holmes, who took over in May. “Because believe me, we’ve been working.” In June, said Holmes, the center served 1,110 families, or about 3,000 individuals. Tillman said that the agency as a whole has seen a sixty-two percent increase in need since April 2019.

The Future?

The GCFD has been working for the past few years to use data to better understand food insecurity and to more effectively allocate resources. “At the same time,” said Greg Trotter, “we’ve also committed to putting racial equity at the forefront of our decision-making. We are still early in this journey.”

In mid-July the Food Depository announced plans to disburse an additional $1.3 million in emergency grants from both state and GCFD funds to community partners, the majority of them serving low-income Black and Latinx communities throughout Cook County. The vast majority of the grant funds, said Trotter, will be distributed by the end of July. Still communities continue to make do on their own.

On June 4, with the South and West sides reeling in the wake of vandalism and looting following protests against the killing of George Floyd, an ad hoc group gathered in the parking lot of a boarded-up strip mall at 54th and Wentworth and gave away 500 chickens. The organizers—who included Todd Belcore, executive director of the nonprofit Social Change, Cook County Circuit Court Judge Erika Orr, and Ta’Rhonda Jones, an actor on Empire—had met just that week when they’d been called to a meeting with Mayor Lori Lightfoot at Chicago Police Department headquarters. The mayor didn’t show up, but the group decided to join forces on their own to do some good. Kasey Rush, Rep. Bobby Rush’s daughter, offered her father’s campaign office (later revealed as the site where CPD officers relaxed during the May 31 looting) as a command center, and three days later they were in business.

In addition to the chickens, donated by Tyson, the group distributed fruit and vegetables, cereal, doughnuts, and diapers. It was a decidedly low-tech affair, with the food heaped in piles on tarps on the asphalt. Volunteers from other neighborhood groups like R.A.G.E. chipped in and all in all they served an estimated 800 people, said Jones.

Before the pandemic, Social Change focused mainly on amplifying community voices to affect public policy, seeking to drive state and local government to address racial and economic inequity. But right now, said Belcore, “People are hurting and we want to do everything we can to respond to that hurt. We’re a policy organization, but if we have to gather diapers and vegetables, that’s what we’re doing to do.”

Belcore’s sentiments were echoed July 10 by Berto Aguayo, the cofounder of Increase the Peace, an antiviolence program based in Back of the Yards. Increase the Peace isn’t usually in the food distribution business, but when the pandemic hit, the group mobilized its volunteers to help out at Casa Catalina. After the looting and unrest in the wake of the George Floyd protests, the group started to stage their own “Black and Brown Unity” pop-up food pantries in partnership with groups like, on this day, La Casa Norte.

Some Back of the Yards residents are unwilling to go to a traditional food pantry, said Aguayo, because they can’t, or don’t want to, provide identification, or information about their place of residence. Sometimes they are just put off by unreliable hours of operation which, during the pandemic, may be constantly in flux. Or maybe, he said, they just don’t feel welcome.

Increase the Peace is known in the neighborhood for cookouts with teens and other “positive loitering” activities designed to reduce gun violence; during the May 31 looting, volunteers were on 47th Street trying to protect local businesses. When more established groups like this get into food distribution, no questions asked, said Aguayo, it can make residents feel safe because there’s a relationship of trust already in place.

In early June, said Increase the Peace organizer Julia Ramirez, there was a surge of enthusiasm from people anxious to help, but that energy has already dissipated.

“That always happens. It’s specifically, like, the people on the North Side were coming. … And then you don’t see that anymore. It’s not really that rush and that urgency,” she said. “But the organizations that don’t necessarily do like food pantry or food distribution, I think that that has to be one of their main initiatives moving forward.”

“We’re trying to model what a pop-up food pantry could look like for other organizations,” said Aguayo. “What I envision is for the Greater Chicago Food Depository, or Catholic Charities, or these other big organizations to come out of their bricks and mortar and meet people where they’re at; meet them on the street corner.”

“Like a lot of organizations, we had to pivot to meet basic need,” he added, as a line of volunteers ferried 1,200 boxes of fruits and vegetables across the street from the Huntington Bank parking lot to tables set up alongside La Casa Norte’s drop-in youth shelter at 47th and Hermitage.

“Especially after the riots, we realized we can’t teach people about policy and community organizing if they’re hungry.”

This story was produced through a partnership between South Side Weekly and the Social Justice-Investigative specialization at the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University.

Martha Bayne is managing editor of the Weekly. She last wrote about the timeline of and police response to the May 30 George Floyd protests.

Kari McMahon is a journalist from Scotland covering business and technology. She is currently studying at the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University.

Maura Turcotte is a journalist from Los Angeles studying at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism. She tweets at @mcturcotte. She last wrote about muralist Brenda Lopez for the Weekly.

Kari Lydersen leads the Social Justice-Investigative specialization in the graduate journalism program at Northwestern University and works as a journalist and author covering energy, politics, and more.

Thank you for the excellent article! One thing: there is a quote,

“We were using the food as a connection point to actually get people to work, to get people connected to benefits that they weren’t entitled to, that would make it less stressful so we could actually shorten the pantry line,” she said.”

I assume this is meant to say benefits they WERE entitled to?

Yes! You are correct. Fixing that now.