With a fifth wave of COVID picking up steam during the holiday break due to the Omicron variant, a significant number of Chicago Public School (CPS) parents were reluctant to send their children back to the classroom even before school resumed January 3. So far, the new year at school has been short-lived.

After the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) officially voted to switch to remote learning and resume in-person classes on January 18, CPS CEO Pedro Martinez canceled all classes and extracurricular activities, claiming that teachers were refusing to work and threatening to not pay them. Some teachers and parents say they have felt gaslighted by City officials who have attempted to strongarm them into attending school in person despite rising cases and no comprehensive mitigation plan.

As of Monday, January 10, students were out of school for the fourth day in a row and teachers were locked out of their virtual classrooms, unable to directly contact their students. But that night, after days of negotiations with CTU, Mayor Lori Lightfoot announced that teachers would return to school the next day and students would return on Wednesday. The agreement, which passed Wednesday afternoon after CTU members voted with fifty-six percent approval, includes provisions like additional KN95 masks and a switch to remote learning if forty percent of students in a school are in quarantine or if thirty percent of staff are absent for two days in a row. The agreement also allows every school to have a contact-tracing team, allowing staff to be paid to do contact tracing for student cases in their school.

“These are not the exact metrics that we would like to hit, but it provides some safeguard going forward,” said CTU chief of staff Jen Johnson at a press conference that followed a CTU vote Monday night.

Though the CTU has been seeking opt-out testing, which would automatically make every student eligible for a weekly randomized testing program unless parents opted out, Mayor Lightfoot did not agree to this provision. But Johnson said that the tentative agreement would still significantly increase testing in schools, with the aim of quickly ramping up a screening testing program so that at least ten percent of students in every school would be tested on a weekly basis. It is still unclear whether CPS will make up the five lost instructional days or if CTU members will be paid for the days of canceled classes—these decisions will be left up to Martinez.

Throughout the first week of class, Mayor Lightfoot accused the teachers’ union of “abandoning” their kids during this time. Some parents and teachers who spoke to the Weekly characterized the mayor’s rhetoric as harmful to teacher-parent relations. The mayor has since tested positive for COVID.

“She’s trying to punish the teachers, but she doesn’t realize that she’s punishing the kids,” said parent Liliana Rosas.

When her sons returned home from school on January 3, they brought back laptops issued by their teachers with the expectation that they would shift to remote learning the next day. But students and teachers were caught by surprise that morning. Teachers attempting to log in to the CPS website found themselves locked out–a deja vu of last January, when CPS kicked teachers out of their accounts during the pandemic. As CTU and CPS continued their negotiations, Rosas’s younger son, who attends pre-K at Shields Elementary School in Brighton Park, was receiving assignments from his teacher through a separate platform.

But Rosas worried about her third grader at Shields. He has an Individualized Education Program (IEP), a legally required document for children who receive special education to address the child’s needs. In school, he sees a social worker once or twice a week, and last year when school went remote, he was able to meet virtually with his occupational teacher or social worker. “I haven’t received no email or something from a teacher regarding him, what he needs to be doing. I know he needs that extra help and he’s not receiving it right now,” Rosas said.

While they waited days for a resolution, Rosas tried to continue her son’s learning by encouraging him to use educational apps, do math, and read. “But it’s not gonna be the same as a teacher teaching him, like someone that is educated and has a degree. I don’t have that. So I can’t teach my son what a teacher could—even remotely,” she said.

On Wednesday, January 5, the Brighton Park Neighborhood Council (BPNC) held a press conference alongside Raise Your Hand IL and Alliance of the South East. “We are worried and afraid that COVID will continue to take lives away if wrong decisions continue to be made,” said Jazmine Cerda, a parent organizer, at the presser.

She said teachers and students have been in a push and pull with CPS since the start of the pandemic, and two years later some of the same problems have persisted. “Why are we still here?” Cerda asked.

“We are fighting for a remote option for parents who are afraid to send their children to school because cases keep rising, schools are not properly being disinfected, many students are putting themselves on the line because they have tested positive,” she continued.

Another parent, Jennifer Baez, spoke about what happened when her ten-year-old child tested positive prior to winter vacation. A parent from her son’s school replied to an email thread directed at the principal; Baez said they asked the principal, “Am I to understand that you just announced the closure of a fifth grade classroom via Facebook?”

The principal, admitting to having notified parents and students with a Facebook post, confirmed that class was canceled, Baez said. She hadn’t seen the post or been made aware of the closure until that moment. “{I had} a lot of emotions happening at once because I had already sent my son out the door to go to school, and had I not seen that email my son with special needs would have just been sitting in the lot at the school waiting to go in, and nobody would have come out to get him,” she said.

Upon the cancellation of the class, the fifth graders were assigned to remote learning for the time being. The remote class was led by a substitute teacher and Baez later discovered it was their regular teacher who’d tested positive. The next day, when her son began to feel ill, he tested positive as well. Baez also tested positive.

Citing official claims that schools have low positivity rates, Baez said she thinks that this is mostly attributed to parents noticing when their children are sick and just refusing to send them to school without reporting a positive test. The voluntary CPS testing program that sent take-home testing kits to families over winter break proved to be a logistical nightmare that had FedEx mailboxes overflowing with packages on New Year’s Eve. According to CPS data, 24,843 out of 35,590 of the completed tests-by-mail were ruled invalid.

CPS officials have held that schools are safe, saying that there has not been evidence of widespread in-school spread of COVID, that there were only fifty-three instances of outbreaks in the fall, and that less than five percent of students who quarantined were found to have COVID. At Monday night’s press conference, Mayor Lightfoot said that during remote learning last year, CPS lost contact with 100,000 children, nearly one-third of the student population.

The Principals and Administrators Association reported that about the same number of students missed in-person class on January 3 and 4. They wrote in a public letter that they were blindsided by the CEO and called for a districtwide strategy. “It should not be an ad hoc reactionary response that creates inequities that are predictable among social and economic lines,” the January 6 letter read in part. “It feels as if the district’s approach was more focused on eroding the trust we’ve worked so hard to develop by pitting schools, principals, parents, and staff against each other than on actually providing safety and support for students and communities.”

The majority of suburban school districts and other districts downstate held classes remotely on the first week of school after the holiday break and have continued to do so as of press time. The Illinois Department of Public Health’s dashboard continues to show that schools are the place with the highest potential for exposure.

Catlyn Savado, a youth organizer and freshman at Percy L. Julian High School, said, “I heard the CEO himself say yesterday that ‘every one of our kids are wearing masks in school.’ The CEO was at my school on Monday and I know he didn’t see every high schooler at my school with a mask on.”

In a CTU poll, teachers responded that high-quality masks for students are a higher bargaining priority than masks for themselves.

As of January 4, CPS reported 446 new student cases and 276 new adult cases, more than double the previous daily record this school year. There were also 7,951 students and 2,076 adults in quarantine (isolation), the highest number since the start of school, that has since been surpassed, with almost 10,000 students reported to be in isolation on Friday, January 7.

There are wide disparities in vaccination rates across high schools in CPS. Chalkbeat found that majority Black high schools had an average vaccination rate of twenty-eight percent, compared to schools with fewer than half of Black students, which had a vaccination rate of 57.62 percent. Opt-in rates for school-based testing also vary, and some South and West Side schools have almost no students opting in.

A CPS middle school teacher who prefered to remain anonymous, was out of the classroom when students returned from winter break because they’d contracted COVID. “I was already teaching remotely Monday and Tuesday,” they said. “Tuesday evening they were doing the vote with the House of Delegates with the CTU.

“We were going to send messages to students [the next day and] send them some remote work or enrichment to do while the classes were canceled, but we had been locked out of everything: Gradebook, parent contacts, Google Classroom, email, all of that stuff we are still completely locked out of, so there’s no way to communicate with parents or students,” they said.

The teacher added that parents rely on communication with teachers in order to stay in the know. “For a lot of students and families, their main source of trust and communication is that child’s homeroom teacher. Teachers at my school really pride themselves in making that relationship with their parents: texting, calling, emailing, sending updates. And so when that was locked out and not able to [be accessed], I know that was really difficult for parents to even reach out with questions.”

Bill Schmit, a teacher at Lindblom Math and Science Academy in Englewood, described the result of the spike in COVID cases after the holiday break in his classes. “My attendance numbers on Monday and Tuesday were abysmal. I’ve never had such low attendance in my career,” he said. “The last couple of weeks [before the winter break] were so disruptive with students being in and out that, for all of its shortcomings, remote learning would have been a far more equitable option for everyone,” he said.

He described having to juggle teaching in-person with ensuring his students in quarantine were being taught the lessons remotely as well. “I’m not very big on remote learning. Personally, I had a horrible time with it and I did not want to go back to it,” he said. “But for the sake of this wave and how many kids were getting sick, I didn’t see too much of an alternative.”

Brittany Nash, a teacher at Henry R. Clissold Elementary in Morgan Park, said, “This fight, the ones before, and the ones to come, are always, at the root, about the students and the teachers.”

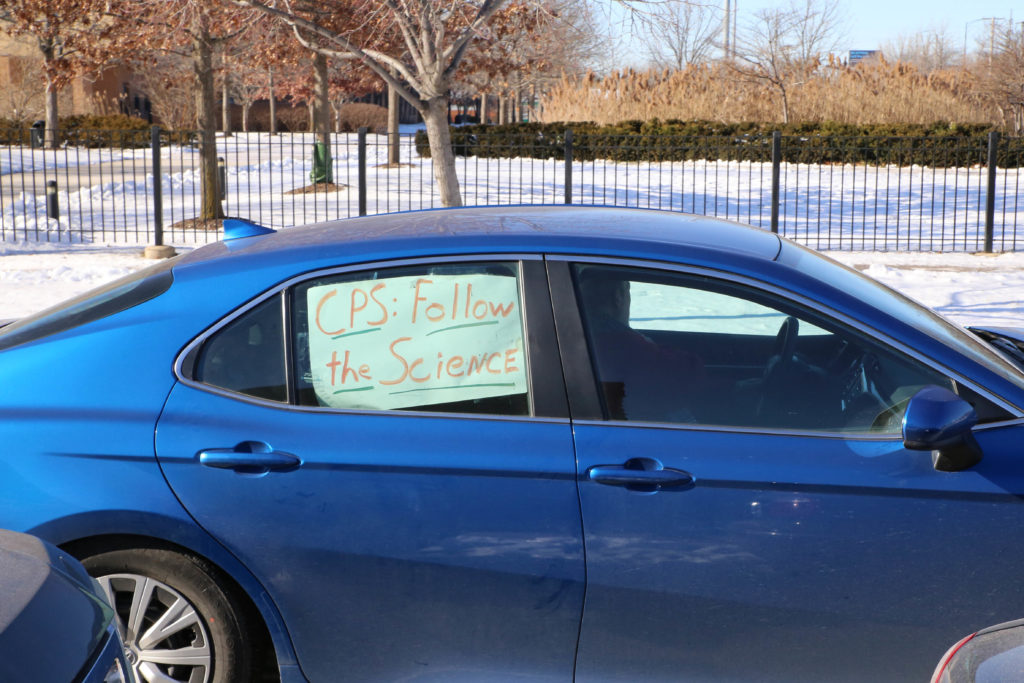

On Monday morning, hours before CPS and CTU reached a deal, teachers and parents from West Side high schools and schools across the city organized a caravan to City Hall. Around lunch hour, they congested downtown, honking their horns and waving signs in support of a comprehensive safety plan that called for temporary remote learning and weekly testing.

“It’s been powerful standing with the union and realizing that it is much bigger than me, my classroom, and even my school,” Nash said. “It’s hard hearing that teachers don’t care, they don’t want to work, they don’t want to support families and students, which is exactly the opposite.”

Update, January 12, 2022: This story was edited after publication to include the CTU vote on January 12.

Madeleine Parrish is the Weekly’s education editor, Chima Ikoro is the Weekly’s community organizing editor, and Jacqueline Serrato is the Weekly’s editor-in-chief.