Earlier this summer, Illinois expanded Medicaid coverage to undocumented adults 42 and older. Hundreds of immigrants who became eligible have already signed up for the low-income healthcare subsidy program, which serves 3.3 million people in the state and 1.6 million in Cook County alone.

Yet any Medicaid recipients who attempt to access mental health care services may face a common problem: a shortage of therapists who will accept them as patients.

Vanessa Baie practices part-time as a psychotherapist in downtown Chicago. Half of her patients are enrolled in Medicaid and every one of them has said how surprised they were to find a therapist.

Mental health providers are paid significantly more per session by private health insurers. For many therapists it is unaffordable to accept Medicaid in their practice, making it difficult for aid recipients to find mental health support. “As a therapist you choose your clients—you can decide whether you want to take those with higher-paying insurance or Medicaid,” said Baie.

Baie was candid about her Medicaid caseload. The only way she affords to take on so many Medicaid patients is because the insurance pay-outs supplement her full-time income, which she earns while working towards her PhD. Her livelihood is not dependent on her psychotherapy practice.

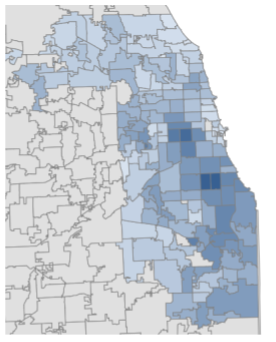

The shortage of mental health providers accepting Medicaid disproportionately impacts the South Side, which has a higher percentage of Medicaid recipients than other parts of the city.

In neighborhoods like Kenwood and Woodlawn, where around thirty percent of residents live below the poverty line, thirty-one percent and fifty-nine percent of people are enrolled in Medicaid, respectively.

For therapists, the difference between sessions funded by Medicaid and sessions funded by private health insurers varies between $50–90 per session. While the difference paid by the insurer can be as small as $12, patients with private health insurance co-pay an additional amount. In Baie’s case, accepting Medicaid-funded patients means she earns approximately $400 less per month, based solely on session fees. This number doesn’t account for canceled sessions. Patients enrolled with private health insurers pay late cancellation fees out-of-pocket—but when Medicaid clients miss sessions, the therapist bears the cost.

“It’s like working on commission,” Baie said. “You get paid per session, but you also have to pay your overheads.”

The size of the difference often makes it necessary for therapists to favor patients with private health insurance, rather than just financially enticing. For many it is unaffordable to take on Medicaid patients, while also keeping up with rising costs, significant overheads and burdensome student loans. Overhead costs can be as high as $50 per session. While the cost per session decreases as more cases are taken on, overheads remain the same whether the therapist is reimbursed at Medicaid’s rates or by private insurers.

Jessica Kuhnen, a licensed clinical social worker in Hyde Park, said she feels like a “sell-out” for not accepting Medicaid patients. However, to earn enough to support herself and her practice, and continue repaying student loans, Kuhnen is reliant on the higher rates paid by private health insurers.

As a result, Medicaid patients are severely disadvantaged when seeking mental health support. Wait times are longer and options are limited, particularly when the patient seeks a therapist with experience in their culture, race or sexuality.

Katie Prout, 35, has first hand experience with trying to access mental health care as a Medicaid recipient. “It would have been easier for me to access drugs on the street than it was to find therapy,” she said. Prout eventually connected with an intern therapist after some months of searching, but finding a psychiatrist to evaluate her and provide official diagnoses was harder – this took nine months.

To Baie, the system is oppressive. “The populations we see on Medicaid are often oppressed populations,” she said. “The whole system where therapists who see Medicaid patients make less money just plays into the existing systems of oppression and racism and ensures they continue.”

Emma Ricketts is a lawyer turned journalist. She has experience working in a New Zealand-based commercial litigation team focusing on climate-related risk and is currently working towards a Master’s in Journalism at Northwestern University.

I am sure what you are describing affects Medicaid patients and providers across the country. Is there any movement to increase the rates that Medicaid pays to these providers?

“The populations we see on Medicaid are often oppressed populations,” she said. “The whole system where therapists who see Medicaid patients make less money just plays into the existing systems of oppression and racism and ensures they continue.”

You had written a pretty wholesome article until you had to include that last paragraph. Now you’re invalidating everything you’ve done by pulling the proverbial (and overused) racecard. It’s ecominic policies you should have labeled as the problem (which it is). But instead you claim leftist rhetoric to look foolish and bow down to your political and corporate masters…..the only ones who are truly continuing the racist and separatist movements. Shame.