This story was originally published by the Illinois Answers Project.

In October, the city’s top environmental official told City Council members that Chicago is “laser-focused on collaboration and bold solutions” to help homeowners battle flooding problems.

Angela Tovar then pointed council members to the program RainReady, created in Chatham to provide grants to homeowners in the South Side neighborhood to install flood-control devices on their properties that can significantly reduce susceptibility to flooding.

RainReady is the brainchild of a local environmental nonprofit group the Center for Neighborhood Technology. The program has had several iterations in Chatham since its development more than ten years ago by CNT and a group of residents.

RainReady works, according to homeowners—including residents in west suburban Oak Park who benefited from the low-cost flood prevention fixes including rain gardens, backflow valves and cisterns. It is so successful that there is a waiting list, officials said.

But it didn’t get the chance to work for most Chatham residents, the Illinois Answers Project learned. Despite Tovar’s assertions and the city’s promise to launch it in 2019, RainReady has yet to get off the ground. The few Chatham residents who did receive RainReady grants worked directly with CNT prior to 2019.

The different outcomes potentially highlight the difficulty of administering the RainReady program at a larger scale.

While CNT walked away from the city’s project in 2021—citing a lack of “staff capacity” in an email to Sean Wiedel, then an assistant commissioner at CDOT in charge of citywide services—the nonprofit group found a way to work with government agencies outside of Chicago on similar projects. A CNT official suggested that Chicago presents unique challenges.

The village of Oak Park made the project work on a smaller scale. Data shows that its RainReady program that ran between 2017 and 2021, administered by CNT, left neighbors satisfied with the results.

“People were looking for solutions. And this is one of the things that we were trying to … provide,” said Oak Park Neighborhood Services Manager Jeff Prior.

Despite its success, the future of RainReady is unclear in both communities. The village is looking for a new administrator for the program and is uncertain whether grants will be awarded this year, despite opening applications in March.

The city also is searching for a new partner to run its RainReady program. Until it finds one, Chatham will benefit from other programs that the water department has implemented, said Brendan Schreiber, chief engineer of sewers at DWM. Those include Green Alleys and Space to Grow, Tovar said in a statement.

“They’re getting resources that we spread across all fifty wards,” Schreiber said.

Why Chatham Floods

Chatham is flat, low-lying and sandwiched between two of the city’s big reservoirs that collect rainwater, making it one of the last neighborhoods to empty into a sewer system that can often already be full.

A confluence of topography, aging infrastructure and limited funding have made the neighborhood—known for its distinct architecture and history of Black art and culture—a point of struggle for the longtime residents who’ve invested in it.

In a 2017 analysis of flood insurance data by CNT, Chatham was ranked highest in insurance payouts for flood damage. One-fourth of residents affected by flooding surveyed by CNT reported flooding damages cost them at least $20,000. And in 2023, Chicago’s 8th Ward—where most of Chatham is located—had the fourth highest number of 311 calls for flooding in the city.

Ora Jackson has lived in the historic community for forty-seven years. She still remembers the first time her basement flooded several years ago after a day of heavy rainfall. Her grandson, who had converted the basement into an apartment, called her from upstairs in a panic.

She rushed to the basement to find him standing on his mattress surrounded by water. He was terrified to wade his way to the stairs, fearing he could be electrocuted.

“It was frightening because I’d never seen anything like that before,” said Jackson, who told Illinois Answers she had no clue how severe the flooding problem in her duplex would grow over the years.

After enduring multiple floods in her duplex—and continually replacing rugs and furniture and paying out of pocket to repair damages—Jackson finally found some relief when she joined the resident steering committee for RainReady in 2014 and received a grant.

“We were just desperate for anything,” said Jackson, who got her downspout disconnected and a rain barrel installed through the program. “It was an education for everybody.”

Harriet Festing, an environmental activist who worked for CNT when RainReady was designed, said she was shocked to hear widespread “horror stories” of flood damage were in Chatham.

“People couldn’t live in their homes anymore because the mold was so bad,” she said.

RainReady’s early steps in Chatham were successful, Festing said, because the program tackled urban flooding by focusing on small measures that could direct rainwater away from homes to reduce or avoid the basement seepage that resulted from water pooling around the home.

Long-time Chatham resident Lori Burns received a free inspection through that early program. She paid for the installation of a rain garden and backflow valve at her home and another garden at her mother’s home in Calumet Heights.

The results: the basements at her two properties never flooded again, she said.

Burns, fifty, called the result “fantastic” in an interview with Illinois Answers.

“And that’s why we thought we were going to be able to expand again. Really bring it to the city and say, ‘Look, we have proof of concept,’” said Burns, who was among the group of residents working with CNT to develop the program in 2014.

But the city’s program sputtered and Chatham residents in recent years faced some of the most significant flooding damage in years.

“We needed for it to work, so that 2023 didn’t have to be as bad as it was,” said Burns.

For Oak Park resident Nicole Chavas the flooding wasn’t as bad.

Chavas said that when her neighbors were struggling with flooding in July, the RainReady-subsidized rain garden helped prevent water basement seepage in her Victorian home. In contrast, she and her husband found their basement flooded with rainwater after a torrential storm in 2020.

Chavas says that the rain garden along with other flood prevention devices the couple installed on their own make them more prepared for serious rain.

“It was all like doing what it was supposed to be doing and that was a really rewarding feeling,” said Chavas.

The village is susceptible to flooding for many of the same reasons that Chatham is—including aging infrastructure and low-lying topography.

Bill McKenna, the village engineer and co-director of the Public Works Department, said that after spending several years studying flooding patterns in the community, the city determined that a home-based solution program would work best.

Testing resident interest, Oak Park launched a pilot program in 2016 that granted $1,300 each to ten homeowners in the village. In 2017, the village expanded the program to include thirty homes and concluded the pilot in 2019.

“By doing those projects on private property … we can relieve the burden on the village’s sewer system and reduce the likelihood and severity of sewer backups in people’s basements,” McKenna said.

What Happened to RainReady Chatham?

The city’s plans floundered for years in bureaucratic back-and-forth and delays due to the pandemic, records show.

Years of negotiations and bureaucracy slowed RainReady’s implementation to such an extent that not a single Chatham resident of the forty planned participating households received grants from the program, according to records from the city.

The city’s water and transportation departments in August 2016 began negotiating an agreement with the MWRD to test a pilot program in Chatham, due to outreach by CNT and residents.

In 2019, the city’s Water and Transportation departments struck a deal with the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District to funnel $600,000 from the city and the MWRD into a pilot expanding the program. The City Council and MWRD’s board of commissioners signed off on the agreement and it went into effect that year.

The plan included a $400,000 commitment from MWRD and $200,000 from the city. CNT would administer the program and be reimbursed by the city for any costs associated with running the program.

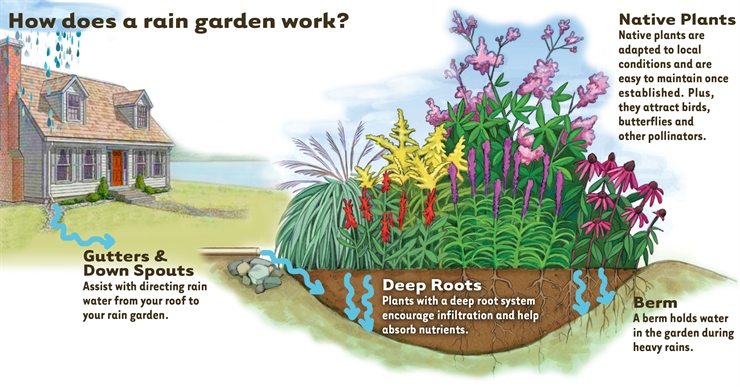

Under the agreement, the program participants would receive assessments to determine the appropriate flood control devices for their homes. Those devices included rain gardens, which use native plants to collect and absorb rainwater runoff from roofs, driveways, and other surfaces, and backflow valves which prevent sewage from backing into basements when the system is at capacity.

The program empowered CNT and its contractors to coordinate inspections and installations. CNT was also responsible for surveying participating households for feedback over time.

Invoices from CNT acquired through a Freedom of Information Act Request show that CDOT paid CNT at least $36,000 for work related to the program between October 2019 and May 2020.

After progress on pilot study halted due to the pandemic, the three agencies agreed to revamp the program and extend its deadline to the end of 2022. But shortly after the amendment passed, CNT’s then-CEO Robert Dean, told the city in an email that it could no longer continue as program administrator.

“CNT no longer has the staff capacity to administer construction related programs of this nature. We remain strong supporters of the concept… but playing the role described in the above agreements is no longer within our organization’s skills set,” the email read.

Illinois Answers asked CNT why the organization no longer has the capacity to run the program in Chatham but is still doing so in other neighborhoods.

“We continue to talk to [the city] on a regular basis to try to explore ways to make things happen,” said Ryan Scherzinger, a project manager at CNT overseeing the $6 million RainReady project recently funded by Cook County for six suburbs in the Calumet City Corridor. “Working with the city… has its challenges. I’m not sure that we’ve cracked that nut, so to speak.”

Still, Tovar boasted about the program’s future in that October meeting and told aldermen that the city is energized to “protect our most vulnerable Chicagoans.”

A November memo from Tovar to a City Council committee shows that $800,000 was budgeted for the RainReady Chatham program. Nothing had been spent.

Reporting on equity issues by the BGA is supported by Joel M. Friedman, president of the Alvin H. Baum Family Fund.

Sidnee King is a reporter for the Illinois Answers Project.