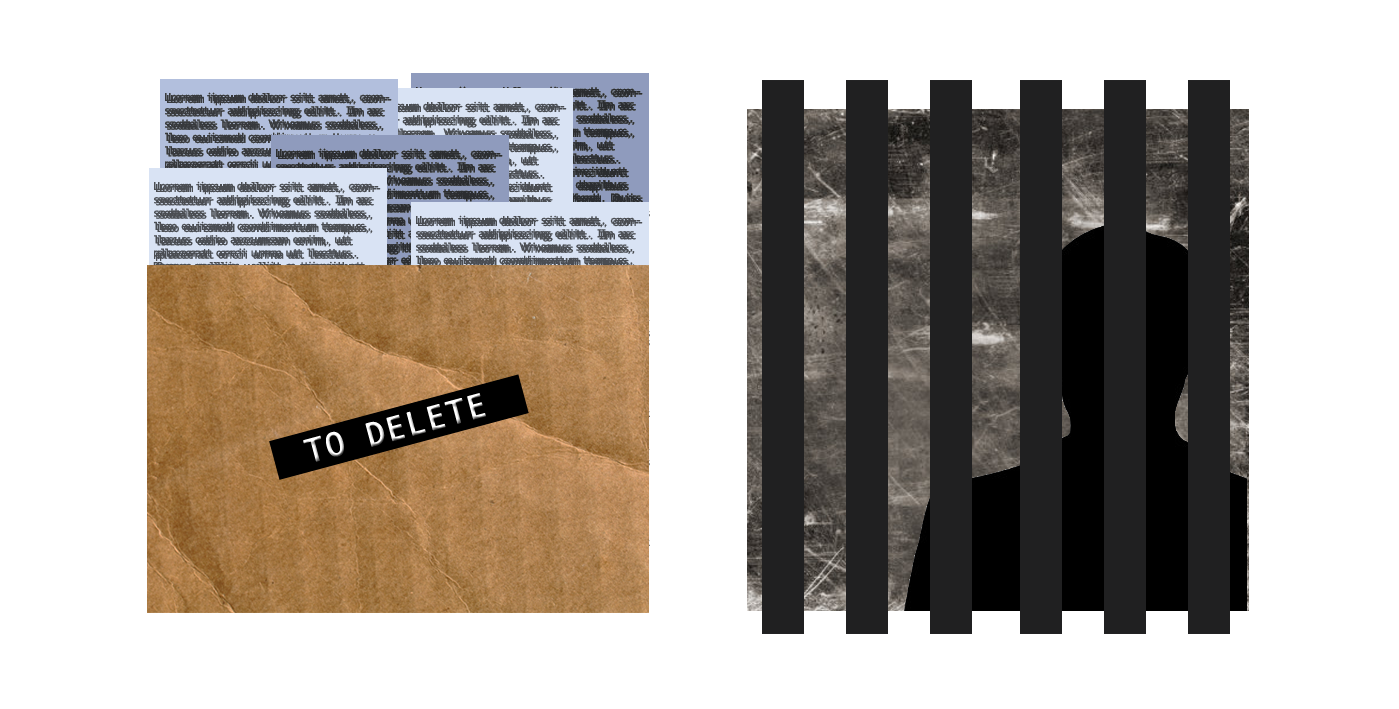

Somewhere in Chicago, on computer databases and in filing cabinets, sit thousands of old police misconduct records dating back to the 1960s, unused and gathering dust. Soon, they will see the light of day—or go straight into a shredder.

In January, an arbitrator in the dispute between the City of Chicago and the Fraternal Order of the Police ordered the city to destroy all records of police misconduct that are more than five to seven years old. And in November, the Chicago Police Benevolent and Protective Association, the union for higher-ranking police officers, won a similar ruling.

The destruction of old police disciplinary records has been a part of Chicago police unions’s contracts for decades. However, only now have union efforts to enforce this part of their contract yielded results. In the 2014 lawsuit, Kalven v. City of Chicago, the Illinois Appellate Court ruled that police misconduct files are public records, which can be released according to the Freedom of Information Act. In response, police unions filed a grievance against the city, arguing that the preservation of these records, let alone their public release, violated the unions’s contracts. They were granted an injunction, halting the release of most of the older documents, while arbitration continued between the city and the unions.

Now that arbitration is coming to a head. The arbitrator in the FOP case, George Roumell Jr., is expected to make a final order on the records’ destruction in April; in the meantime, the city and unions are to negotiate over which records will be destroyed. The files will not disappear without warning due to a ruling that the city must notify the media two weeks before destroying any records.

The unions contend that maintaining these files is unnecessary, and a clear violation of their contracts with the city. The city has argued that the unions have been aware for decades that these records were not being destroyed.

“The City of Chicago opposes the destruction of police disciplinary records,” Chicago Law Department spokesperson Bill McCaffrey said in an emailed statement. “Our longstanding position is that these records have an administrative and legal purpose that warrants preservation, and we will continue our legal efforts to maintain and preserve these records.”

The FOP could not be reached for comment.

The city’s defense of the preservation of old police records comes at a time when its administration is under pressure to increase transparency and regain public trust in law enforcement. Chicago is currently under investigation by the Department of Justice over its police practices, and next month, Mayor Rahm Emanuel will receive recommendations on how to rebuild trust between residents and law enforcement from the Police Accountability Task Force, established in late 2015 after the video release of the Laquan McDonald shooting.

“The idea that at this moment, these documents and this body of information, which we only gained access to recently through our victory in the Kalven case, should essentially go up in a big bonfire is almost inconceivable,” says Jamie Kalven, a human rights activist and journalist with the Invisible Institute.

Kalven, whose lawsuit brought about the public release of police records, says he should not be overconfident about the city’s success in the dispute, because of the “immensely valuable” nature of the information that might be destroyed.

“There’s a lot at stake,” he says.

According to Kalven, these records are essential for identifying patterns of police misconduct and determining whether accountability methods have been effective. As proof of the findings these records could reveal, Kalven points to the Citizens Police Data Project (CPDB) from the Invisible Institute, a searchable online database that compiled police misconduct records from 2001 to 2008 and 2011 to 2015, which were released after the Kalven decision. An analysis of that database revealed, for example, that ten percent of the police force received thirty percent of the complaints, and that African Americans file a disproportionate amount of complaints, which are sustained at a disproportionately low rate.

The CPDB has also given context to individual cases; multiple news sources cited the database to show that Jason Van Dyke, the officer charged with murder in the 2014 shooting of black teenager Laquan McDonald, had twenty complaints filed against him prior to McDonald’s death.

“Just the last four years have been regarded as a kind of unprecedented wealth of police misconduct information,” Kalven said. “So imagine if we had [records], going back close to half a century?”

These records also hold the key to future investigations of police misconduct that aim to overturn wrongful convictions from the past fifty years. Chicago has a history of serious police abuse, including the torture perpetrated by former police commander Jon Burge and the officers under his charge, who coerced confessions from African-American suspects throughout the seventies and eighties.

Burge was fired in 1993. In 2006, a state-appointed special prosecutor concluded that there was evidence “beyond a reasonable doubt” that torture had occurred in at least some of the cases of alleged abuse. By then, however, the statute of limitations on those crimes had run out; no officers could be prosecuted. In response, the state General Assembly created the Illinois Torture Inquiry and Relief Commission, which investigates allegations of torture by Burge and his subordinates.

According to the Commission’s spokesperson Michael Theodore, the Commission received appeals in about 260 cases. About half of those cases have been determined to be beyond the jurisdiction of the Commission, which only covers cases related to Burge. Of the investigated cases, the Commission referred seventeen for post-conviction hearings and dismissed thirty-one; it still has eighty-two cases to investigate.

The Commission uses old records to review the evidence and determine whether a case should be referred to the courts for a post-conviction hearing. However, Theodore says, the Commission does not necessarily know which records it will need for its investigation until it examines each allegation, which happens on a case-by-case basis. If old police misconduct records are destroyed before all the investigations are completed, the Commission may find itself in the middle of an investigation without access to the documents they need.

To prevent this from happening, the Commission’s executive director Robert Olmstead reported at a January 20 meeting that he had served subpoenas for the misconduct records and files of all police officers involved in the allegations of torture. Those subpoenas have not yet been fulfilled.

“These records are vital to our work, and their destruction would pose a great challenge to our ability to investigate these cases,” Olmstead said at the meeting, according to documentation provided to the Weekly.

An appeal of the initial injunction, launched by the city and the Tribune, might be able to prevent the destruction of the records; the case is currently awaiting oral arguments in the Court of Appeals. Another, more long-term resolution to the dispute could come from legislation, proposed by State Representative LaShawn Ford of the 8th District, which would preserve police misconduct records permanently (though new legislation may not apply to existing records).

In the meantime, however, the initial injunction has real-time consequences for those interested in and affected by police misconduct. While the arbitration is ongoing, Kalven says, old records of police misconduct are inaccessible to anyone, from journalists investigating patterns of police abuse to prison inmates trying to challenge their convictions.

For now, they just have to wait. While the situation is still unresolved, Kalven says it’s “hard to believe” the records will actually be destroyed. After all, the underlying issue is the question, who has a right to these records: the public, the police, or the city? And on that issue, Kalven says, the courts have already spoken: “This information belongs to the public.”