Michael Gaylord James leans against the window, legs crossed and one black boot perched on the other, the two “Jesus Garcia for Mayor” buttons on his chest standing out against his sensible winter fleeces. His black-and-white reflection in the window seems like it belongs among the photographs lining the wall next to him: an artist at work, seventy or so years old, surveying his output.

“I walked a fine line between which side of the camera I was on,” he had told me earlier.

Now, no camera sits in his hands, so there are no sides to worry about. James is at URI-EICHEN Gallery to talk at the opening reception of “People at Work,” a show of thirty-two photos he and his son selected from his upcoming collection, “Pictures From the Long Haul.” The haul is indeed long: James has been documenting his travels in black and white since he road-tripped to Mexico City as a college student in 1962.

The shot he snapped there of John F. Kennedy and then-president of Mexico Adolfo López Mateos zipping by in a Mercedes hangs above the newest photo in the show, which shows unionizers at the 2012 Illinois State Fair demonstrating against then-governor Pat Quinn. Other than the photos of Mexico, which predominate, between the bookends of James’s career lies a miscellany of moments: nightclub dancers in Russia, a still-black-haired Obama campaigning for Senate, a barber in El Paso.

James traces fragments of his own story, from bourgeois Westport, Connecticut, through his time at Lake Forest College and later in several social justice organizations. Though his work as a community organizer taught him the importance of documentation, that’s not quite the reason for his ceaseless snapping; nor, it seems, was his upbringing among artistic types in Westport.

“I don’t quite know what moves me to take the pictures,” James says, a bemused sentiment he likes to repeat. “I just did.” For James, the work of photography is intuitive.

It’s thanks to his son, David Libman, that James even bothered to develop many of his thousands of negatives. When Libman was working at a photo lab in the late nineties, James gave him the JFK negative. “I think you have a show here,” Libman told James when he saw the resulting print.

Although James’s artistic ambitions have grown since that moment of validation—he expressed confidence in an imminent public breakthrough, as well as a desire to make movies—his artistic pretensions haven’t. He remains proud of his photographic ignorance: “I know you got light and all that stuff. Four hundred film and you shoot it such-and-such.”

If he knows some of the photos on view are overexposed, he doesn’t show it. Libman, who studied photography in college, has no complaints. In fact, he says he’s learned from James’s honesty-as-art method.

“To me it’s a different experience,” Libman said, hands in his coat pockets, having arrived too late to snag a folding chair. “It’s not a photographer who has these high ideals about composition and making a statement. This is a reflection of his travels and the people he meets. He pops a shot. A lot of his shots are sideways.”

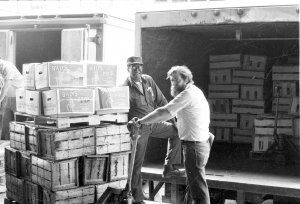

So aesthetic concern is secondary. Fair enough; “People at Work” suggests a focus on political content anyway, and James chose this theme because URI-EICHEN’s owner is a labor organizer. Decorations on a corkboard near the entryway include an Occupy Wall Street poster and an anti-gun illustration. URI-EICHEN often exhibits shows with a left-wing activist bent, dealing with subjects like migrant labor and drones, and has served as a meeting space for union activists.

Somewhat disappointingly, there is little depth to the portrayal of labor in the photos. Libman called James’s enormous collection of prints and negatives “an archive of his life experiences,” which is exactly correct. James’s photos of people at work are often not photos of the people so much as they are photos of his experience shooting them.

In one photo, a Nicaraguan daycare worker’s smile hovers between irritation and charm, an effect of James’s gregariousness, as does the expression of a worker at a Chicago street market in another. The captions below the photos are characteristically loquacious tangents that center more on James’s experiences than on what’s in the frames. James did not step into these people’s lives and their work; they stepped into his. What results is a biography in reverse, of the person at work on the other side of the lens; a fine line indeed.

Perhaps it’s misguided to expect a more rigorous exploration from photos that were shot without sophisticated intention. Although most merely happen to depict people working, sometimes the focus is more than nominal. While Libman explained that each photo was an experience from James’s life, he stood in front of a 1962 shot of blues musicians, Muddy Waters and James Cotton, performing in Chicago. This photo is the show’s best, a joyful blur of cheeks and crooning mouths that emerge from complete darkness while their suits melt into it. Unlike the other photos, it’s an experience from the subjects’ lives, one that James captured fully while omitting his own presence. It says, simply: this is our work, this is what we do, and we love it.

James probably understood such joy. In the boundless rambling stories he and his friends told at the opening, negativity was notably absent. James’s work—the art, the activism, the occasional acting, the radio show, the café, the books-in-progress—seems anything but a burden to him, despite its volume. Still, James was reminiscing about the civil rights movement when he suddenly added, “I never did as much as I thought I should’ve.”

Later, with the audience, his outlook brightened. He described his idea for a new story, of “an old guy” who ventures into the prairie in 2016 with a camera and an old car he’s tuned up. “I think there are a lot of ideas in his head,” James said, as his friends in the front chuckled approval. The work continues.

URI-EICHEN Gallery, 2101 S. Halsted St. Closing reception Friday, February 6, 6pm-9pm. Hours by appointment. (312)852-7717. uri-eichen.com

Thank you JULIA AIZUSS