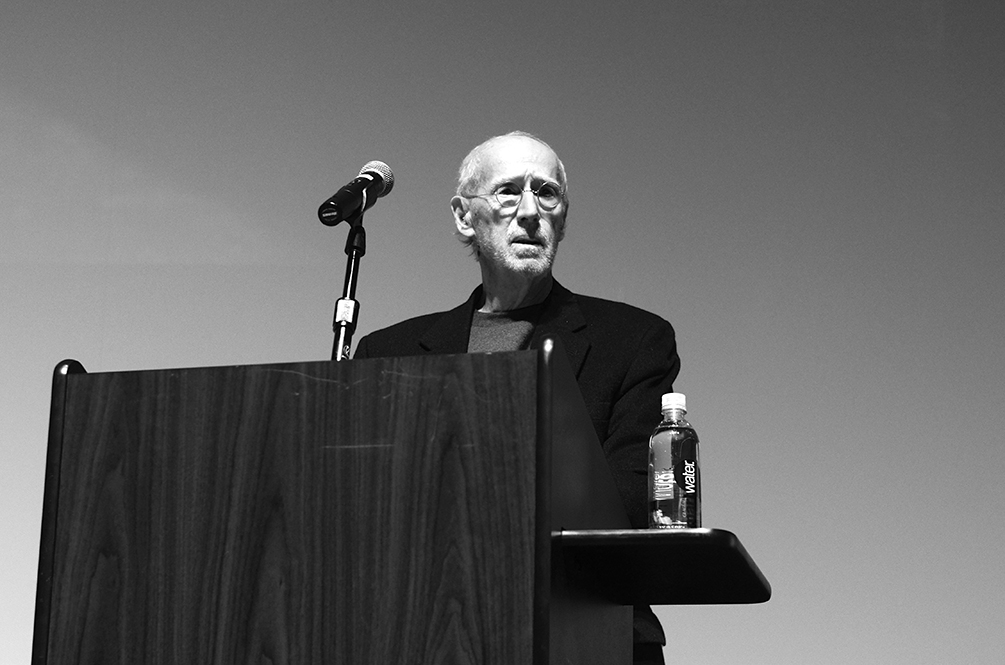

No one in the packed Logan Performance Hall knew quite what to expect when Robert Morris first took the stage and made his way to the podium. Morris spoke slowly with a deep voice that verged on monotone, unassuming but with a sure presence. His first task was correcting Professor W. J. T. Mitchell’s introduction, which got the new name of Morris’ talk wrong. No longer titled “Is a Pound of Passivity Worth a Pinch of Pique?” as advertised, Morris changed the title to “A Few Thoughts On Bombs, Tennis, Freewill, Agency Reduction, the Museum, Dust Storms, and Magnets” at the last minute.

As he took the stage, the large screen directly behind him lit up with an image of a much younger Morris standing behind a similar podium many years ago. Juxtaposed with that image was present day, eighty-two-year-old Morris, who now looks more like an aged professor or elderly relative than one of the key figures in the history of twentieth century art. Dressed in a black blazer, pants, and shoes, with a grey turtleneck underneath and a pair of wire-rimmed glasses perched on his nose, he would blend into a crowd rather than stand out. But as he shuffled slowly back and forth from one podium to the other podium (he had two onstage), musing about everything from physics, to tennis, to ravens, it was evident that the audience hung on his every word.

Morris spent his first few minutes on stage telling the audience about how he’d refused to give talks for twenty years, and doesn’t want to talk about his old art or be interviewed about it. To Morris, “Contemporary art makes enough noise without me.” Yet for all his protestations, Morris came willingly to the Logan Center that night to give this talk, share his knowledge with university students and faculty, and speak about his previous work. Nevertheless, Morris seemed like to remind us that, “I also think I could have said no.”

For all the pomp and circumstance surrounding his talk—two introductions, his past works projected as a slideshow behind him in the “presence of most of Chicago’s art world”— Morris never took himself or his audience too seriously. He delivered his messages with a hint of whimsy. He leisurely strolled to the podium to offer up anecdotes, often swearing or coming up with a cleverly disturbing distillation of the modern world. One was about fighting for one’s country, or “the right to say motherfucker,” in which a young man went back to war, several times, ultimately loosing a hand, an eye, and both legs. After two combat tours, society finally deems his sacrifices “good” enough, letting him remain home. At least now he can say “motherfucker” with prideful patriotism.

Morris spent a large part of his talk critiquing modern society. He pointed out that we pride ourselves on our “innate” rationality, but that it is really all based on assumptions. “Rationality will not save us,” Morris says, as it supports our belief in self-interest, which perpetuates “evil.” Self-interest, according to Morris, requires a “‘what the fuck’ attitude.” To all this, Morris simply says, “WTF?”

Morris also critiqued agency reduction—the continual visual reduction in art, starting with analytic cubism—as a larger critique of culture. This trend of “doing less in art,” he says, “is never separate from culture. Art must tell us what we are.” Morris furthered this by arguing that as art does less, the museum does more, becoming a more social, performative space. Morris believes this focus on the spectacle “leads to passive viewership and less critical engagement.” He then offered up an anecdote of a young man who pops into a gallery, takes a picture of the wall label, and walks out without even looking at Morris’ piece, exemplifying his claim that, today, passive engagement with art from behind an iPhone camera is the norm.

But Morris is more than a pessimist. Deeply fascinated by physics and philosophy—he frequently quoted Richard Feynman, Bertrand Russell, and John Cage—Morris came off as sage, rather than condescending. For Morris, art is a means to deal with the contradictions of the world. These contradictions are reflected in his works, especially in his labyrinths—mazes, which he calls dialectical experiences, “reminiscent of the tension in my work between exterior clarity and inner confusion.”

Though his work characterizes a struggle to understand a world full of crippling contradictions, “Morris makes us feel anything is possible,” according to Professor Mitchell. He goes on to state that Morris’ work is, “too experimental, various, and unpredictable,” for him to be consigned to history just yet.

After an abrupt, haunting ending in which Morris described a spider on a piece of burning firewood, resigned to the inevitably of its death, Morris still had one trick up his sleeve. “I’ve agreed to take a few questions,” he said, cutting through the applause. A man raised his hand to ask a question. Much to everyone’s surprise, Morris answered by pulling out a black hat, filled with pieces of paper. Stooping down to pick one up, he read, “ ‘This is our paradox because every course of action can be made to accord with the rule’—Ludwig Wittgenstein.” Morris proceeded to give quotations from Bertrand Russell and John Cage until he “ran out of answers.” Then, he scooped up his hat and walked off the stage in the same slow, steady manner in which he came.