When Ytasha L. Womack, author of the newly released “Afrofuturism,” walked into 57th Street Books for a chat and signing this Saturday, she didn’t immediately stand out. Upon closer inspection, however, there was something a little more offbeat to this young woman with the bright smile and lively presence, dressed stylishly in black: her bracelets and rings carried strange, intricate illustrations, and she wore lipstick and eye shadow the color of a blue raspberry Jolly Rancher. Her book talk, too, began innocuously enough, with Womack telling the story of how she was exposed to the expansive universe of black culture within science fiction and other popular media in her college years. But it quickly veered off to touch upon, among other things, the idea of race as a type of technology (i.e., a man-made creation), how alien abduction relates to the slave trade, and how science fiction can be used to revive past cultures as well as imagine future ones.

As a popular explanation of a theory that has long been present in African-American academia, Womack’s talk was heavily sprinkled with relatable pop-culture references. Womack updated and explained longstanding ideas, providing the audience with a clear description of what exactly Afrofuturism is.

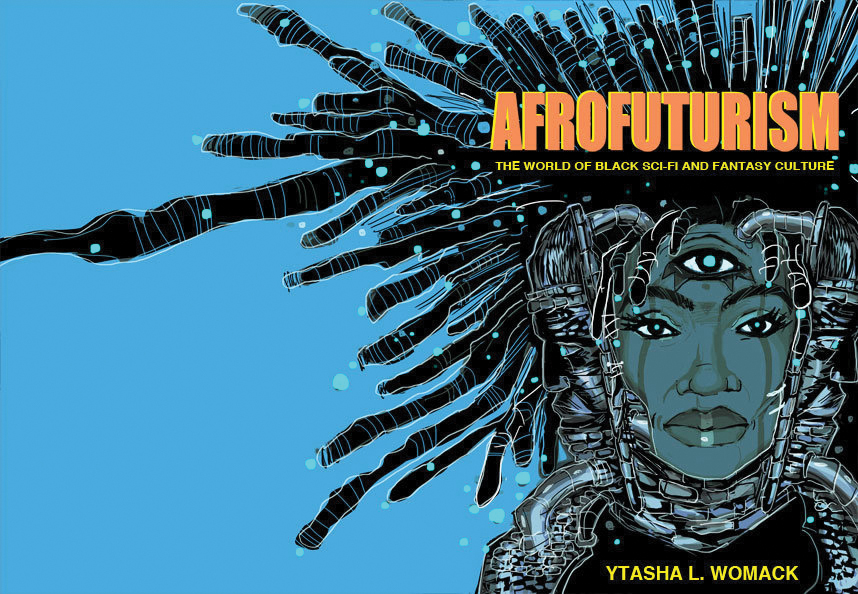

Afrofuturism (both the book and the artistic movement) is, according to Womack, about “the intersection between black culture, technology, liberation, and a little bit of mysticism.” The marginalization of African-Americans within science fiction and fantasy has been well documented. (Take, for instance, the slightly tongue-in-cheek, though often fairly accurate assertion that the black guy always dies first in a horror movie.) Afrofuturistic works attempt to rectify this by imagining a world of mostly black characters, or future societies that have distinct connections to African cultures like the Yoruba or Dogon. It is also an optimistic vision, positing that current struggles and challenges can be overcome to produce a post-racial, fully equal world.

Womack conceives of race as a weapon created a couple hundred years ago in order to justify discrimination against and enslavement of Africans. In nature, she writes, racial divisions don’t spring up in the same way tribes or cultures do; racial divisions are a social creation, invented mostly by Western Europeans in order to justify early enslavement of Africans by portraying them as inferior. By removing the designation of race, imposed originally by outsiders, Afrofuturists hope to encourage all people to choose which groups they want to belong to for themselves. Afrofuturism, Womack claims, can “take you to a space where you can look at yourself and your world more objectively.”

At 57th Street Books, Womack was a charismatic, engaging presence, deftly answering audience questions and explaining some of her more complicated ideas. Her book, on the other hand, is not always so clear. A deeply personal piece of journalism, “Afrofuturism” overflows with purple prose, stuffing pop-culture references and space-laden metaphors into stilted, awkward sentences. At other times, she reaches for short, pithy summation, but simply leaves the reader feeling confused and alienated (pun intended) from the text. Still, the ideas presented in her talk can be found in greater detail in the book, making for a reading experience that is often deeper and more interesting than a brief chat. Her explanations of ancient African cultural motifs that continually resurface in Afrofuturist art and literature—as in the music of space-jazz legend and South Side fixture Sun Ra or the sci-fi novels of Octavia Butler—are intriguing and concise.

As she finished her talk, Womack looked at her audience’s stunned expressions and quipped: “You all look like you just got off a spaceship!” Chuckles rang out around the room, which included two men who once helped Public Enemy shoot a video in Chicago, Sun Ra’s self-proclaimed greatest fan, and a man who took copious notes and rang out with exclamations of assent after every one of Womack’s sentences. People began to mill about and voice their thoughts, which appeared to be some combination of agreement and mild confusion. Womack herself finally sat down, picked up someone’s copy of her book, and signed her name. “I’ll be here for a while,” she said knowingly, “answering people’s questions.”

Afrofuturism, Ytasha L. Womack. Lawrence Hill Books. 213 pages.