- Best CTA Welcome Sign: Cermak-Chinatown Red Line Station

- Best Melodies of Mainland China: Mr. Huang aka Trumpet Man

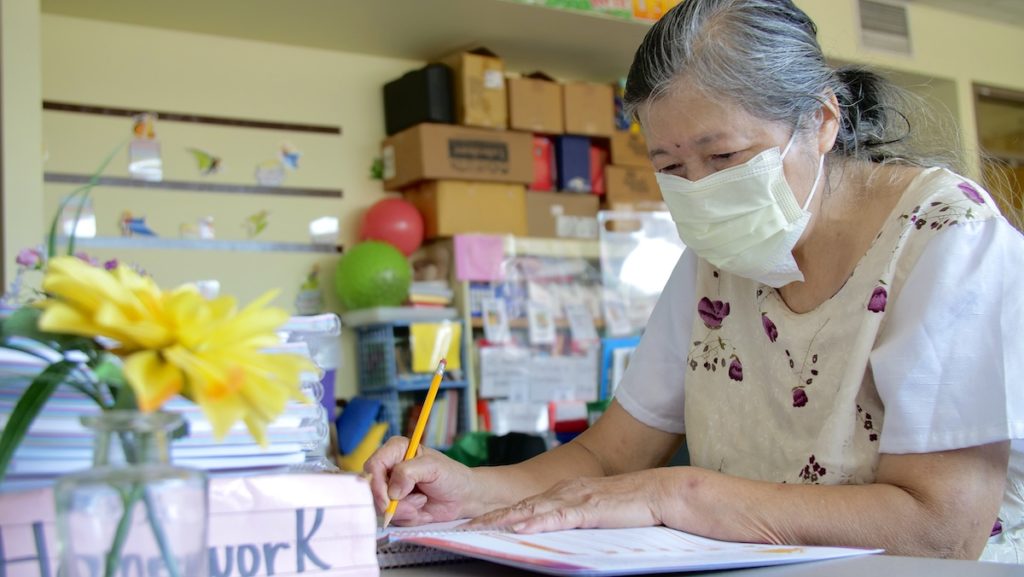

- Best Neighbor to Pay It Forward: Nancy Liang

- Best Intersection for a Modern Roundabout: Intersection of Archer/Cermak/Princeton

- Best Place to Picnic and Be Married: Ping Tom Memorial Park

They outnumber bubble tea shops and dim sum spots. They’re on busy streets and side streets. Their signs might be written in English, or right-to-left. They are not open to the public, but if your family is from China, you might already be a member of one of these exclusive clubs.

They are Chinese family associations. The one Gene Kong belongs to, the Soo Yuen Benevolent Association, has existed in Chicago since 1924. It was first founded in San Francisco before chapters began springing up wherever Chinese people settled. “The Chinese started moving east,” Gene said, laughing as he added, “As opposed to Americans, [who] moved west… A lot of these family associations started out in the west coast.”

Soo Yuen’s office is up to the ceiling in sunworn family association photos. In many of them, people are bunched shoulder-to-shoulder in their Sunday best at chapters in California, the Philippines, Cuba, China, and more. Some chapters appeared large enough to populate a small village. Beside those frames on the wood-paneled walls are photos of Hiram Fong, the first Chinese-American senator and candidate for president.

“Back then those Chinese people, most of them were men—it was a bachelor society back then—they came to this country looking for work. So these family associations, if you’re lucky and your surname fell in that category, you can go to them for assistance… Maybe you need an address. How do you send money back? You get letters sent to here,” he said, referring to the association offices. “This was kind of their official address back then, before P.O. boxes.”

Family associations provided social services and helped recent immigrants get their footing in America. Nowadays, those services are carried out by professionally staffed nonprofits such as the Chinese American Service League and Pui Tak Center. “Right now it’s mostly a social club. They have income, so maybe just have a little party for the Chinese New Year.”

“It was real simple back then. I’d go to school here, Haines School or St. Therese… We grew up around here, we went to school here. During the summer when school’s over, we’d see our friends during the summertime. Nowadays, it’s not like that now. Kids that go to school with them may be out somewhere else… They don’t see their classmates because they’re all scattered.”

Gene grew up in the generation where Chinatown had no nearby parks, but they would play at Haines when it used to have a baseball yard. “Before, Chinese people wouldn’t go to White Sox. A lot of discrimination back then.” He also remembers going to the library when it used to be across the street from his family’s association. There’s even a picture of it in one of the association’s old publications, which is written almost entirely in traditional Chinese.

Gene excitedly showed us to the small office den and pointed out their charter as well as all the important people and politicians who have paid visits. Then, he shared some words of advice about civic engagement.

“You younger people should always vote regardless. Remember in politics there’s no good or bad. Voting is the reality of lesser of two evils. The simplified Chinese version [of the character for ‘party’] means friend… Jesus had a friend: Judas. Betrayal comes from within.”

When asked about his thoughts about the growing representation of Asian Americans in local government, Gene seemed ambivalent. “It’s good to have this. The problem is, in my opinion, are we ready for this? Just because you’re in politics, there’s always that unseen hand behind them. I hate to sound cynical about this, but are they actually working for us? This is still Chicago, a lot of the old guard is still there. They’re not gonna give up right away to you. Don’t get me wrong, I love my own people. But in the same token… little, old factions, that’s the hardest part… unity is hard. There’s no messiah returning from heaven.”

He was intensely pragmatic, but nonetheless incredibly supportive of young people getting involved in politics, just as he once was. He claims he’s voted every year since he was eighteen.

Like for many visitors to the area, the best thing about Chinatown for Gene is the availability of comfort. Chinese, Asians, and non-Asians alike have claimed something homey about stepping into these busy, fragrant corridors, perhaps not knowing that each bite of food is flavored with the past and our own love for Chinatown. “Best of Chinatown for me is being able to go across the street and get a wonton noodle. Even if I had money, I’d probably still live here. I worry that if I move out, this is my identity. I’m just so used to it.”

Phan Le is a Bridgeport resident and a Chicago Chinatown history enthusiast.