A seemingly simple dot, the Bindu is in fact a powerful Indian symbol that represents the point at which creation begins and may become unity. In a collaborative exhibition at the Bridgeport Art Center named after the Bindu, artists Paula Garrett-Ellis, Mareev Vaid, and Stacey Sirow explore the symbol’s deeper meaning in a collection of works that spans folk art, contemporary printmaking, sculpture, and photography. Within these pieces, the artists search for unity in a clash of cultures and customs—between India and America, past and future, tradition and modernity.

The gallery itself serves as a space for this cross-cultural unity, sheltering visitors from snow outside with sweet, samosa-scented warmth and the soft strumming of traditional Indian music. At the opening reception, gallery-goers in brightly colored saris and shawls mingled with others bundled up in black sweaters and scarves. After lighting an oil lamp in a traditional Hindu ritual, the spectators dispersed to inspect the work on the walls, which ranged from depictions of classic Indian iconography—like the Kalighat Cat and Ganesh, the elephant god of wisdom—to more modern silkscreen interpretations of these symbols.

“Western ‘modernity’ and non-Western cultures are in constant conflict on how to maintain an indigenous tradition and how to incorporate the new world,” said Lelde Kalmite, the exhibition’s curator. “In ‘Bindu,’ we have an unusual combination of art from two expatriate Indian and American women artists who explore the pressure from Western culture to remake the world in the Western mold.”

The first of these expats, Paula Garrett-Ellis, was born in America but moved to India after her husband relocated to New Delhi for work. Even after moving to a new country, Garrett-Ellis wished to create opportunities to continue making and displaying her art. She organized a project called NOWARTINDIA, a group made up of international and national women artists living in New Delhi. Together, these women collaborate to organize studio exhibitions and shows in order to continue sharing their search for self amid new environments and cultures.

While in India, Garrett-Ellis was struck by the cultural sacrifices that accompany modernization and the evolution of symbols within an urban way of life. In particular, she felt that the prevalence of plaster mannequins of women and children in marketplaces and malls typical of the thirties, forties, and fifties encapsulated these trends. While adorned in traditional Indian garb, these gaudy mannequins exhibit the faces of a Westerner: fair skin, blue and green eyes, blond hair. Many modern Indian women aspire to these Western ideals of beauty and strive to alter their natural appearance by using bleach to lighten their skin and blue contacts to change their eyes.

“Why?” asks the artist. “Why Bollywood, why bleach, blue contact lenses, white skin? In becoming globalized, so much is lost, so much natural beauty and priceless tradition.”

In “The Why Project,” Garrett-Ellis probes these questions by creating a series of silk-screen prints of women’s faces. In one of these pieces, she paints the jagged features of a woman’s visage in an unnatural, garish yellow hue. Her bright orange hair juts in spikes from her scalp while her smeared red lips scowl. Along with bright blue eyes that unabashedly glare outwards, her demeanor captures a seemingly universal discontentment with appearance that leads to the desire to fit a certain “ideal” mold.

While Mavee Vaid, an Indian woman working in America, is also concerned that her heritage is losing out to modernity, she chose to explore this topic by showcasing traditional Indian folk art from a variety of artists who capture the narratives of Indian mythologies. The collection, entitled “Deccan Footprints,” explores the tension between humans and nature in India of the past and present. She hopes that these pieces remind people all over the world of the beauty of India and open their eyes, hearts, and minds to the Bindu in order to bridge cultural differences.

In a piece called “Kundalini,” Indian artist S.H. Raza paints a series of repeating concentric blue and black circles that are reminiscent both of a dormant, coiled snake and the shape of the Bindu. The third artist featured in the exhibition, Stacy Shirow, also aimed to portray the energy and spirit of India by designing interactive water pots which try to reproduce the sounds she associates with her native country.

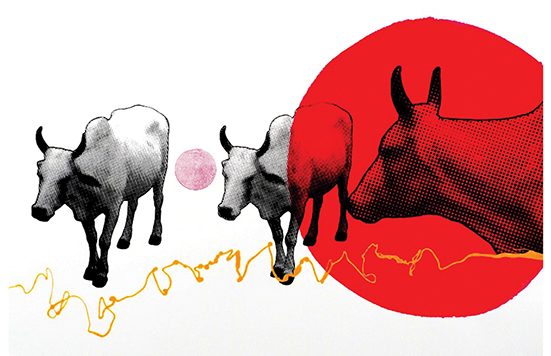

By weaving circular motifs within her works, Garrett-Ellis ultimately unifies the exhibition through the subtle interplay of traditional cow symbols along with modern art-making techniques. In one image, a pulsing ring of circles emanates from the middle of a cow’s forehead, epitomizing the relentless beat of the Bindu—a rhythm that will continue to unify humans even amid the inevitable trends of modernization and globalization.

“Bindu,” Bridgeport Art Center, 1200 W. 35th Street. Through February 28. Monday-Saturday, 8am-6pm; Sunday, 8am-noon. Free. (773)247-3000. bridgeportart.