A black man lies in a white room on a white bed, a white woman draped around his body in the shape of a question mark. She is asking him something.

“Don’t you ever think about how sad it is, the way people treat each other?”

“Not really.”

It’s the scene that opens Kofi Ofosu-Yeboah’s Akata, a short film that follows an acclaimed black artist as he navigates life in a city where his blackness is stereotyped: the movie’s running gag is that he can’t catch a cab.

Akata was one of five short films shown at Black World Cinema’s monthly screening in the unfinished Studio Movie Grille in Chatham, all of which were directed by former or current graduate Astudents in Columbia College’s film department. The lineup included a film of cut-together archival footage, as well as two movies directed by members of the Kinfolk Collective, an artistic community that documents stories from the African diaspora. For his part, Yeboah is currently trying to crowdsource funding for Chicago I See You, a documentary about the Concrete Kings, a street theatre group that works to expose and defeat systems of institutionalized racism.

Akata mines similar territory at the intersection of race and art. During a Q&A with the audience after the screening, Yeboah explained that, in the languages Yoruba and Fante, an akata is a wildcat that doesn’t live at home. It’s often a denigrating term when used by African peoples to describe the African-American community, but in his film Yeboah shows how, in America, the word becomes divorced from its original meaning and is instead applied indiscriminately to all black people.

“We do not account for the history of the black person—the racist system they have had to face in this country. Africans have a better infrastructure and support system,” says Yeboah, who himself is Ghanaian. “But akata is also the African in America. There, no distinction is made between them.”

Yeboah’s exploration of how this ethnic nuance often collapses into one overarching category—black—is at times subtle, at times a little heavy-handed. “Do you need me to call a cab?” the main character’s partner asks him at one point, and the unspoken implication lands with all the subtlety of a jackhammer. The rest of the dialogue often feels similarly overwritten, with the exception of a strikingly powerful poem written and performed by the film’s lead actor.

But from the beginning, Yeboah’s eye more than makes up for this clumsiness; in the opening scene, he lays out the central tension—a black man in a white world—elegantly and without didacticism. At the film’s climax, Yeboah lets the camera linger lovingly in and around the setting, a car parked underneath the trestles of a railroad.

The night’s other standout, Savage vs. the Void, is more overtly political. It is set in 2011, on the night when the state of Georgia executed Troy Davis, a black man convicted of killing a Savannah police officer. Director Darren Wallace said he wanted to make the movie as a way of working out his own complicated feelings about the death of Davis, stemming from his own work advocating for Davis’ exoneration.

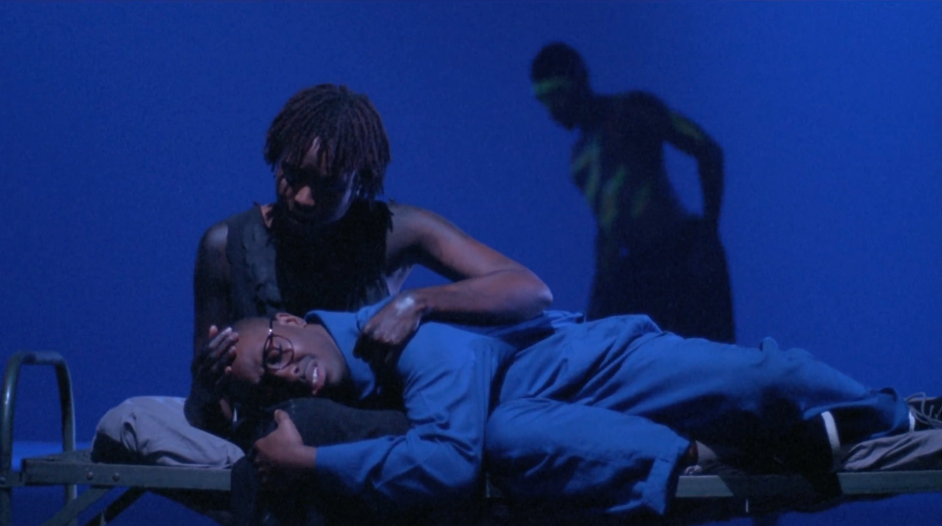

The film follows a director and set of actors who are putting on a play about the events surrounding the Davis execution. Savage, the lead actor in both the play and film, objects to the idea of performing the execution on stage when it looks as if Davis will be granted a stay of execution in real life. The director, Reuben, argues with Savage, contending that the martyrdom of Davis, even if it only takes place in a play, advances the cause of racial justice and immortalizes Davis.

Savage vs. the Void is deeply cynical about the possibilities of art, but it’s also a lingering, artistic work of beauty. Wallace’s enactments of scenes from the fictional play are particularly memorable, including one containing a haunting rendition of Gil Scott-Heron’s “Home is Where the Hatred Is.” In fact, the film is molded by music: in the opening shot, Savage sits in his dressing room, humming Lauryn Hill’s “If I Ruled the World.”

“I use music as another character,” explained Wallace afterward. “In a couple of scenes, I put bossa nova in there to play against or accentuate the themes.”

Ultimately, the debate between Savage and Reuben is rendered moot: Davis is executed anyway. “A man, not a martyr,” Savage-as-Davis shouts defiantly after he receives his lethal injection, given by a nurse who dispassionately lists off its components. But Savage’s protest is hopeless—Reuben bounces up on stage afterward, thrusting both fists in the air, proclaiming his artistic triumph. Savage lies on the stage, exhausted. It is not clear who is right.

While these two films were the most impressive of the night, the other three—which included Shades of Shadows, a chopped up fever dream scored by the sunny Chicago soul band The O’My’s—also showcased promising talent. More importantly, however, all of the films aroused an energy in the room that curator Floyd Webb quickly pounced on, announcing the impending publication of a new magazine, Southside Cine, devoted to covering film on the South Side.

“For too long, the conversation around film has been confined to the North Side,” said Webb, who has worked in the Chicago film scene since the mid-eighties. But if the quality on display this past Thursday is any indication, the geography of Chicago’s film scene could soon begin to shift.