The Bungalow

The Bungalow

The Chicago bungalow—sturdy, low slung and emblematic—is here to stay. Perfect roosts for big shoulders, bungalows account for almost one-third of Chicago’s single family housing today, and have been an aesthetic and residential staple in the lives of Chicago communities and families for over one hundred years. Most sit arced in a crescent framing the western swath of Chicago—from Lincoln Square in the north, through the West Side to Auburn Gresham in the southwest and down to kiss the lake at South Shore. This so-called “bungalow belt” fosters some 80,000 residences and eighteen historic neighborhoods. A true Chicago bungalow must meet several criteria, including a construction date between 1910-1940, a brick face with a stone trim, a low-pitched roof, and an offset entrance, often on the side. These, among others, allow for conservationists to identify and help preserve historic bungalows as a distinctly Chicago architectural style. (Jack Nuelle)

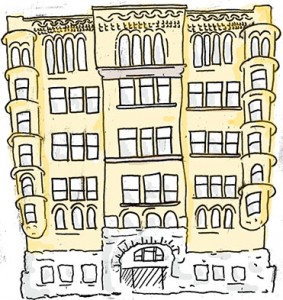

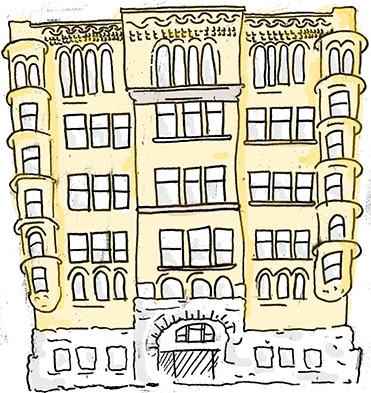

Yale Apartments

Yale Apartments

Constructed in 1892, the Yale Apartments in Englewood still stands, handsome and proud. It is a solid example of the Romanesque Revival style popularized by architect Henry Hobson Richardson, who incorporated 11th and 12th century French, Spanish, and Italian influences into his work. In addition to detailed and elegant facades, the building incorporates a twenty-five-by-eighty-foot skylight in its atrium, dramatic even today. It was restored at a cost of $9.5 million in 2003—for a long time it had been vacant and was slated for demolition—and won city landmark status in April of the same year. Its original fifty-three two- and three-bedroom apartments have been divided into sixty-eight one-bedroom apartments, which are now rented at affordable costs to seniors. Once a symbol of the middle-class property boom in Gilded Age Chicago, Yale Apartments now provides a dignified residence to Englewood community members who need it most. (Emily Holland)

Trumbull Park Homes

Trumbull Park Homes

Built in 1938, Trumbull Park Homes was one of the first three housing projects of the CHA, constructed by the federal Public Works Administration in 1938. The building is made of brick and, in keeping with other Chicago housing projects, angular and utilitarian, subordinating form to function. The homes—which sit at 105th Street and Yates Avenue—were originally erected in an all-white neighborhood, and so, due to unspoken CHA policy, only white residents could move in. In 1953, however, the CHA mistook Betty Howard, a fair-skinned black woman, for white and allowed her to move into the homes, thereby integrating Trumbull. Race riots ensued, with attackers targeting Betty and her husband Donald’s home. Out of this conflict came a call for further integration in Trumbull homes. Ten more black families moved into the complex that same year, leading to further riots. Trumbull Park Homes, and its history, still stands today. (Emma Collins)

The Greystone

The Greystone

Greystone buildings, characterized by their limestone façades made from southern Indiana stone, are brick homes usually two to three stories tall, though some reach up to six stories. The style was utilized from the 1890s to the 1930s, when middle class residents were the most popular tenants. Limestone is easily carved, and there were primarily two architectural motifs used in construction: Romanesque, characterized by arches and cornices, and Neoclassical, incorporating bay windows and columns. An estimated 30,000 greystones are left in the city. The Ida B. Wells-Barnett House, which housed the journalist and activist Ida B. Wells from 1919 to 1929, is one. Located between 36th Street and 37th Street on Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, and employing a late-nineteenth century Romanesque style, the home is a prime example of this quintessentially Chicago architecture. (Jason Huang)

Muhammad–Farrakhan House

Muhammad–Farrakhan House

In James Baldwin’s 1962 essay “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind,” he recalls a dinner he had in a Hyde Park mansion with the Prophet Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam and mentor to Malcolm X: “I looked again at the young faces around the table, and looked back at Elijah, who was saying that no people in history had ever been respected who had not owned their land. And the table said, ‘Yes, that’s right.’ ” While the mansion which stands today at 4855 South Woodlawn is not the one Baldwin visited—it was constructed later, in 1972—it is a testament to the persistence of the vision Baldwin heard expressed by Elijah and affirmed by his disciples. After Elijah’s death in 1975, the Nation of Islam split into two factions: one was led by his son, Warith Deen Muhammad, who embraced Islam and moved away from the black nationalism which characterized his father’s leadership, founding the American Society of Muslims. In 1977, Louis Farrakhan, who had served as a prominent minister under Elijah, led a group of Black Muslims to revive the name “Nation of Islam.” Warith Deen inherited the twenty-one-room house, its marble floors and crystal chandeliers, as well as the smaller houses built across the street where disciples lived. In the summer of 1985, Black Muslims protested his rights to the building—a 1986 Hyde Park Herald article describes them “brandishing picket signs and chanting” that Warith’s retention of assets which belonged to the organization made him “a traitor to his father and community.” In 1986, the Black Muslims were able to purchase the building—with the help of donations, bank loans, and a $5 million donation from Moammar Gadhafi, whom Louis Farrakhan, who lives in the house, once called a good friend. While the house and what it represents may not always inspire respect from all who behold it—the Libya connection, reports of Farrakhan’s anti-Semitism, and the Nation of Islam’s financial troubles all remain sources of controversy—it certainly demands attention. (Rachel Lazar)

Illustrations by Isabel Ochoa Gold.

Thanks, I loved reading here about Elijah Muhammad’s properties in Chicago. But all I find is info on his 1970-built properties. I read James Baldwin’s essay some years ago and wondered, where is the OLD mansion, the one where James went to famously dine and discuss matters with the prophet and his N.O.I. in 1961? I wish to see (without trespassing) that porch where the two figures stood and shook hands before departing. Pray do tell please.