City leaders are trying to prepare in case of another surge of migrants after at the Republican National Convention last month, Texas Governor Greg Abbott warned that he would continue to bus migrants to cities in blue states, and claimed that he would send as many as 25,000 migrants between now and the National Democratic Convention.

The arrival of Venezuelan migrants in Chicago and top Democratic hubs has been used by Republicans to promote anti-immigrant sentiment and overwhelm city resources. While blasting Democrats’ immigration policies, Abbott declared that Texas will keep sending migrants to Chicago and other sanctuary cities “until we finally secure our border.” These remarks come in weeks before Chicago will have the national spotlight hosting the Democratic National Convention and the world will be watching.

In a July meeting on Immigrant and Refugee Rights, 22nd Ward Alderman Michael Rodriguez brought up the potential surge of migrants arriving this summer and wanted to know if this was budgeted for. Annette Guzman, budget director for the City’s Office of Budget and Management, said it was not.

“We have anticipated through discussions with people at the border… and the comments made by the governor of Texas that we would need upwards of 25,000 beds,” Guzman said. But she noted that there are only approximately 5,000 beds currently available.

“There is no coordination with the state of Texas, but at [the peak of incoming migrants in] October, November and December [of 2023], we were seeing about 2,000 arrivals a week,” she added.

Following President Biden’s temporary suspension of migrants’ entry across the southern border, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported a 29% decrease in migrant encounters in June 2024.

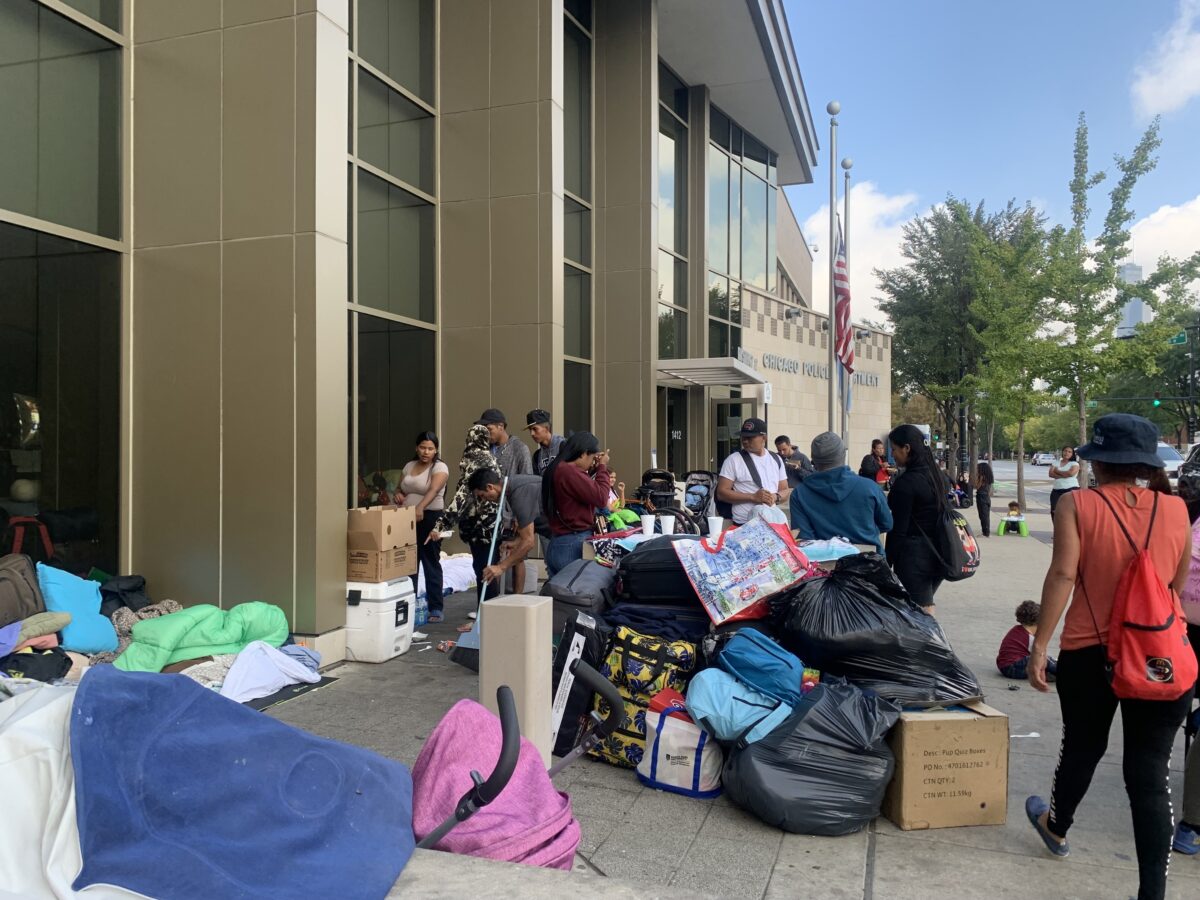

The city has found it difficult to handle the humanitarian crisis, rushing to open makeshift shelters during the winter, while migrants, including children, slept on the floors of police stations throughout the city for months.

The City-maintained arrival dashboard indicates 46,191 asylum seekers have arrived in Chicago since August 2022. Approximately 20,000 migrant children have been enrolled at Chicago Public Schools.

Currently, over 5,000 migrants are being housed in seventeen shelters by the city and state, 2,000 of whom are minors.

“This is from a peak of 15,000 the week right after Christmas,” Deputy Immigration Mayor Beatriz Ponce de Léon said in the July meeting. During this peak, the daily cost of temporary shelter was over $1.4 million a day.

The data from June shows that number has gone down to approximately $680,000 per day.

Last week, the city dashboard reported a total of eight migrants at the designated “landing zone” at 800 S. Desplaines and nine migrants “awaiting placement”—not a drastic increase.

“As you have seen, this has not been a perfect mission, this has not always been pretty, we have had to make adjustments along the way,” Ponce de Léon said. “We have had to be nimble and flexible and course correct and build partnerships that we did not have before.

As of July, over 8,000 work permit applications in the Chicago region have been submitted to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), of which more than 5,000 have been approved.

Some of the partnerships are nonprofits and their local network partners that have been working to support asylum seekers and migrants who have arrived from Texas.

The National Immigrant Justice Center (NIJC) has been helping new arrivals navigate the labyrinth of the legal system to help people remain in the U.S. and obtain employment.

“We’ve been hearing what everyone else has been hearing, that there’s this expectation that the governor of Texas might try to send an increased number of Southwest border arrivals to the Chicago area around the time of the Democratic National Convention,” said Lisa Koop, who is the National Director of Legal Services at NIJC.

“I think looking at it more broadly, the city of Chicago has worked really hard over the last months, and at this point we’re moving into years to set up structures to receive people, to keep people safe to first and foremost, recognize the humanity of people. And obviously, it’s not always been perfect, and systems have been strained.”

“For us, it’s a top priority to help people get stabilized. Oftentimes, that means if we can help someone achieve employment authorization that gives them the tools that they need to move out of shelters and find a stable place to live and get their kids enrolled in school,” said Koop.

Throughout his 2024 campaign and during his presidency, Donald Trump has often issued anti-immigrant rhetoric. During an April campaign speech in Wisconsin, Trump dubbed immigrants “animals” and “not human.”

Just weeks ago, at the National Association of Black Journalists 2024 conference, the presidential candidate used the platform to blast migrants for taking “Black jobs,” something he has done before, controversially, including in a June debate with Joe Biden.

“It’s really sad and disappointing to hear politicians dehumanize immigrants, and treat them as political instruments to further promote negative messaging,” said Koop. “I’m very proud that NIJC is a part of a Chicago community that has countered harmful narratives and has worked really hard to show that we embrace the humanity of everybody that arrives in our communities,” she added.

At the July meeting, Antonio José Reyes Ortega, a Venezuelan migrant wearing a gray sweater with an embroidered Chicago Bulls logo, stood up during the public comment period. He expressed gratitude at being able to stay at a shelter in Chicago, but said he is struggling to get work because he doesn’t have a work permit.

Addressing the people and members of the City Council he said in Spanish, “You’ve provided me with a roof, somewhere to sleep, somewhere to shower. I think that what you do is wonderful. I have tried to look for work. I don’t even know where to go to look for work anymore. I think, every time I go look for work, I go to a place farther and farther away. If it’s farther than I’d been, there I will go. But the answer remains the same, ‘No. Because you don’t have a work permit’ or ‘because you don’t speak English.”’

Alma Campos is a senior editor at the Weekly.