The City of Chicago and its Board of Education have a long history of perpetuating segregation, starting with an 1863 City ordinance that required Black and White students to attend separate schools. Segregation in Chicago’s public schools only intensified when Chicago’s Black population boomed due to the influx of Black Americans from the South in the first half of the twentieth century, and it has been reinforced in the twenty-first century through strategic policy decisions, privatization, and neglect.

In 2013, the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) and then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel closed the most schools ever closed at one time in United States history to combat a deficit in the City’s budget. The fifty school closures meant that more than 11,000 students were displaced and given the option to transfer schools. Former CPS CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennett claimed that the district was able to keep track of where all but seven students landed after their schools closed, but it was later revealed that CPS and the Illinois State Board of Education were actually unsure of the whereabouts of more than 400 students—there was no record for these students of a successful transition to a new school.

A large majority of the schools closed were on the South and West sides of the city where the students were majority, if not completely, Black or brown. Of the fifty schools closed in 2013, forty-two had a population that was greater than seventy-five percent Black, and eighty-eight percent of the students affected by the school closures were Black. Neighborhoods such as Englewood, Austin, and Garfield Park faced the most instability, as multiple schools within a few miles of each other were shuttered or relocated. John Calhoun North Elementary School, formerly located in East Garfield Park, was closed despite having high test scores and performance.

Since the mass school closures, CPS has seen a decline in enrollment every single year, continuing to fuel what some have deemed a vicious cycle of disinvestment. This is also fueled by the ongoing exodus of Black families from Chicago: between 1980 and 2020, the Black population in Chicago dropped from 1,187,905 to 787,551, according to the census. This population loss has led to decreased funding for schools in these neighborhoods; under CPS’s Student-Based Budgeting (SBB) model introduced under Emanuel, funding is allocated to schools based on the number of enrolled students.

“CPS puts these policies into place, including the expansion of charter schools, that lead to a decline in enrollment in [CPS] schools in predominantly Black and poor neighborhoods,” said Carol Caref, an education policy analyst at the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU). “And then those schools, because of Student-Based Budgeting, don’t get very much money, so they can’t offer things.”

Decreased funding results in fewer options for students and makes schools even less attractive to potential families, perpetuating the cycle of attrition. “Parents, if they have an alternative, their kids aren’t going to go to those totally underfunded schools,” Caref said.

The 2013 closures also never translated to better offerings for those students who remained in CPS. After the closures, the district said it would flood the schools receiving the dispersed students with resources. But in the aftermath, the district switched to SBB, and though they provided temporary transitional support, “they never actually did something that would reverse the trend in those communities,” said CTU education policy analyst Pavlyn Jankov. “Instead, they doubled down on tying enrollment changes to the ability of a school to provide things for those students.”

As schools were shuttered in both the 2013 closures and through Renaissance 2010—a program under then-Mayor Richard M. Daley that involved closing eighty CPS schools and replacing them with a hundred charters. Selective-enrollment schools, charter schools, and magnet schools—known for their competitiveness—proliferated while neighborhood schools suffered. Between 2001 and 2019, there were 169 school closures and 193 school openings—only 29.5 percent of openings were district-run schools.

Red pins represent where schools were closed in 2013, while green pins represent where charter schools were opened.

How Did We Get Here? The Origins of School Segregation

Residential segregation in Chicago—a product of twentieth-century restrictive covenants, redlining, discriminatory federal and private lending, and discriminatory housing laws that clustered Black residents in the Black Belt located between 12th and 79th streets and Wentworth and Cottage Grove avenues—set the stage for segregation in CPS. Attendance lines were drawn to match these segregated residential patterns without regard for student population or overcrowding.

Activists in the 1950s and ’60s produced maps that showed how the district maintained Black students in schools with more than ninety percent Black populations under Benjamin Willis, the superintendent of CPS from 1953 to 1966. These maps also showed that “doubleshift” schools—schools where students would attend school in four-hour shifts to avoid overcrowding—were overwhelmingly located in Black neighborhoods. According to a 1957 article in the NAACP magazine The Crisis, the average white elementary school in Chicago had fewer than 700 students, while the average Black school had more than 1,200.

To address this issue, the Board of Education placed students in portable classroom structures made of corrugated steel deemed “Willis Wagons” in the parking lots of overcrowded Black schools instead of allowing Black students to attend majority white schools. Willis became notorious for perpetuating segregation, and many civil rights leaders led protests against him from 1963 to 1965, including hunger strikes, picketing, boycotting classes, and burning mobile classrooms.

Public school officials proposed plans to transport Black students to underutilized white schools on the North and Southwest sides in order to alleviate the overcrowding of Black schools. But across the South Side, like many other places in America at the time, white residents met these changes with anger and violence. Anti-busing movements and protests made it clear that white people would stop at nothing to ensure that Black students were not integrated into their schools. When CPS attempted to integrate schools such as Bogan High School in Ashburn in 1977, white parents protested and aggressively disrupted meetings to sabotage the efforts.

In 1980, after “more than a decade of battles between the federal government and Chicago” regarding segregation in Chicago’s schools, CPS was put under a consent decree and a court-mandated desegregation plan. While the decree was in place, officials relied on voluntary approaches, which included encouraging transfers from segregated schools and establishing integrated magnet and selective-enrollment schools which used race as an admissions factor.

Under these policies, schools remained segregated.

In 1980, eighty-two percent of Black students in CPS attended highly segregated schools where at least 90 percent of the students were Black. In 1989, almost ten years after the consent decree was signed, seventy-five percent of Black students were still in extremely segregated schools. The decree was lifted by a federal judge in 2009. In 2012, three years after it was lifted, seventy percent of Black students still attended highly segregated schools.

After the High-Rises Came Down, So Did the Schools

City disinvestment in public housing—which destabilized families and neighborhoods on the South and West sides—led the City’s investment in schools in these neighborhoods to plummet, as well.

After high-rise public housing developments were demolished under the Plan for Transformation and residents were relocated, adjacent schools slowly began to shutter, as well. Many schools that weren’t closed during the Renaissance 2010 project were eventually closed during the 2013 closures. “There are a number of schools that are along State Street through Bronzeville that were closed down,” Jankov said. “The district response was [that] they aligned the school policy to what they were seeing in the communities, which was this removal of housing investment in those communities.”

Edward Jenner Elementary Academy for the Arts, located adjacent to the Cabrini-Green housing development on the Near North Side, was one of the schools that served children primarily in public housing. After the demolition of Cabrini-Green, the population of the school began to shrink, and soon it was the last remaining school that once served children from Cabrini-Green. The school was threatened with closure, and in 2015, a proposal was introduced by parents to merge Jenner with nearby overcrowded Ogden International School, a school on the Gold Coast whose population was mostly affluent and white. At the time, Jenner was ninety-eight percent Black and predominantly low-income. In contrast, thirty-seven percent of Ogden students were Black.

The Ogden-Jenner merger was an example of a parent- and community-driven integration effort, but to Caref, it was a unique case for a reason. “I think that school—even though it was predominantly Black—was in the ‘acceptable’ neighborhood for white parents. And that’s not true, necessarily, of schools on the Far South Side,” she said.

The Shuffling and Reshuffling of Students

Many students directly affected by the 2013 school closures were forced to transfer to whatever school was nearest or able to take on more students. These mergers dramatically altered the lives of students and parents of closing schools and overcrowded the schools that absorbed them. The majority of schools that were closed in the South and West sides were in predominantly Black neighborhoods.

Black and brown students were disproportionately hurt by these closings, even by those that did not take place on the South and West sides. Joseph Stockton Elementary School was merged with Mary E. Courtenay Language Arts Center in Uptown, and although the school was one of the few closed on the North Side, Courtenay had more than ninety percent students of color, while Uptown is fifty-four percent white. The merger turned the middle school into what parents and teachers described as a “war zone,” filled with constant fighting between students.

According to a 2018 report by the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research, “students affected by school closures experienced negative effects on test scores,” though they experienced no change in their core grade point average (GPA) immediately after closure. But test scores and GPAs alone are not adequate to measure the turmoil faced by students affected by the closure of their schools.

In a commentary on the study, Dr. Eve Ewing, a sociologist, author, and poet based in Chicago, wrote that “all schools involved in the closure process were embroiled in a highly stressful, internally competitive, even antagonistic process that established their institutional futures as being threatened by the institutional survival of their colleagues and neighbors. Given this context… any social cohesion that schools were able to develop whatsoever post-closure should be seen as nothing short of miraculous.

“Ultimately,” she wrote, “we must ask how and why we continue to close schools in a manner that causes ‘large disruptions without clear benefits for students.’”

Underutilization and Lack of Resources

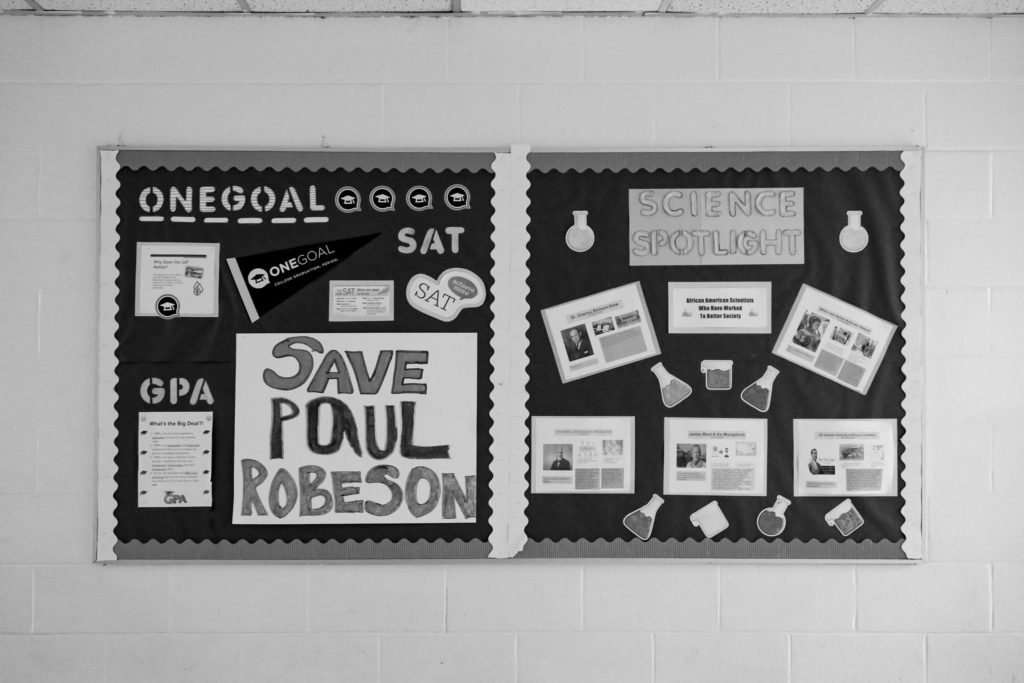

When a school is enrolled at less than seventy percent of its capacity, it is deemed “underutilized” by CPS, even if the school doesn’t have the same resources as better-funded schools to bolster their enrollment—making it susceptible to closure. In 2018, CPS closed Robeson High School along with three other high schools located in Englewood, citing low enrollment. However, these schools were not well resourced. Jankov called this practice “closure by attrition,” saying that “even if you’re a community that is nowhere near getting the services they need in their schools, if you’re losing students, CPS was cutting funding from those schools. So you end up with situations where even if a school didn’t close, your budget has been cut twice, thrice over a period of a decade and a half, and you’re no longer able to provide services.”

In an interview with South Side Weekly, Ewing noted, “Chicago is all one property tax base and one school district. So having more expensive homes in Lincoln Park vs. Englewood doesn’t affect the tax base.

“What does make a difference within Chicago is private fundraising that schools do,” she continued. “Public schools are allowed to fundraise, and since communities with higher incomes are more likely to have disposable funds to participate, this widens the gap in resources further.” Combine this with the per-pupil funding formula, and “neighborhood schools where enrollment has been dropping a ton have just less money to work with than a competitive school that is always fully enrolled.”

Magnet and Selective-Enrollment Schools: A Failure of Integration

Many magnet and selective-enrollment schools in Chicago were created under the desegregation consent decree in place until 2009.

Magnet schools are public schools that have specialized classes and a focused curriculum. Most magnet schools use a lottery system to determine admission, and the consent decree called for the lottery for magnet schools to be “based on race, to ensure integration in enrollment.”

CPS runs a busing program for magnet and test-in schools—which include classical, gifted, and selective enrollment schools—in an effort to attract diverse populations. But a 2019 WBEZ study showed that only twenty percent of magnet and test-in schools met the racial makeup goal of the desegregation court order.

Under the consent decree, race was an admissions factor for selective-enrollment schools, which generally accept applications from across the city and accept students based on grades or test scores. White students, who made up nine percent of the district’s enrollment in selective-enrollment schools in 2009 when the decree was lifted, were allowed up to thirty-five percent of placements.

Jones College Prep, Lane Tech, Northside College Prep, Payton College Prep, and Whitney Young Magnet High School are consistently ranked as the top five public high schools in Chicago. Each of these schools is a selective-enrollment school, and each of them has a disproportionately low percentage of Black students. While the district as a whole is 35.8 percent Black, Jones is 11.6 percent Black, Lane Tech is 6.7 percent Black, Northside College Prep is 6 percent Black, Payton is 9.7 percent Black, and Whitney Young is 17.7 percent Black.

CPS is aware of this discrepancy and utilizes a socioeconomic tier system to rank students based on where they live and weigh their chances of getting into a good school. This system shows that lower-tier areas have less income and less education, while higher tiers have the opposite. In 2012, Derek Eder, a civic technology builder, partnered with Open City to compile data about the meaning of this tier system. The website they created points out that selective-enrollment schools are designed to increase the chances of disadvantaged students of attending better schools by reserving a certain number of seats for students from low-income neighborhoods. “The quota tries to keep wealthier students from dominating selective schools,” according to the project. The analysis concluded that “a high-achieving student from an impoverished area has a better chance of getting into a selective school than a similar student from a richer area.”

Although this provision is helpful for some students, it does not dissolve the clear lines of segregation that determine the fate of a majority of low-income Black and brown students who are confined to neighborhood schools. These selective-enrollment schools are not always nearby or physically accessible, and they have fewer seats. Even now, elementary and high school students from the South and West sides of the city have longer commute times to reach their schools than their counterparts.

Privatizing Education: The Charter Movement

Renaissance 2010 was a project of the Chicago Public Schools backed by business and philanthropic communities. The idea was to “launch marketplace school choice by quickly adding privatized charter schools”; the district would “manage the district like a stock portfolio—phasing out weak schools and schools that would become under-enrolled due to competition,” according to a 2018 article by education advocate Jan Resseger found on the National Education Policy Center website.

These charter schools are publicly funded like neighborhood schools, but they are independently run, somewhat similarly to private schools, and can receive private donations, as well.

A 2017 study conducted by the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research found that attending a charter high school in Chicago led to substantial improvements in test scores, high school attendance, college enrollment, and college persistence. However, critics of the charter movement have pointed to charter schools’ lack of accountability. Unlike district-run schools, charters aren’t required to have elected local school councils. “We’ve brokered the responsibility of educating children to private operators with little-to-no accountability to the public,” said Jitu Brown, National Director for the Journey for Justice Alliance and former education organizer with the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization.

Charter schools are also able to push out students who are not performing up to standards. In 2014, the Tribune reported that charter schools expelled sixty-one out of every 10,000 students, whereas district-run schools expelled only five out of every 10,000 students.

“They come up with creative ways to kick children out,” Brown said. “They call it counseling a child out, and their language is ‘it’s not a good fit.’ But public schools don’t have that option and shouldn’t have that option. Because the school must be ready for the child.”

Brown pointed out that where charter schools are built, the number of Black students decreases, citing the discomfort and alienation students of the shuttered and discarded schools may feel. Despite these schools being open enrollment and available to the public, students from the neighborhood often struggle with reacclimating, and their parents might even decide to leave the school altogether. “It is directly connected to the agenda of moving populations that are seen as undesirable out of municipalities as opposed to addressing the inequities that create the conditions in the first place,” Brown added.

“In many ways, [charters] were sort of created to replace district schools that were segregated, that were underfunded, that were predominant in the South and West sides,” said Jankov. “Those charter schools were opened in those same communities where they closed schools under the pretense that they would be offering something new, something more effective with better results. The reality is those schools remain segregated, oftentimes with either segregated staff or overwhelmingly white staff.”

Between 2001 and 2019, CPS opened 105 charter schools.

Disparities in School Quality: Teachers Work with What They Have

CPS data from the 2020-21 school year shows stark differences in access to quality schools and programs between Black and white students.

The Greater Lincoln Park region, which is eighteen percent Black and fifty-three percent white, has triple the number of high school fine and performing art seats per hundred students as the Bronzeville/South Lakefront region, which is ninety-one percent Black (twenty-seven seats versus nine).

Dyett High School is one school located in the Bronzeville/South Lakefront region explicitly focused on the arts: after hunger strikers prevented the school’s closure in 2013, it reopened in 2016 as a school for the arts, and students can choose one of five pathways to follow: digital media, music, theater, dance, or visual arts. When it reopened, CPS gave $14.6 million in funding to refurbish it, adding amenities including a dance studio and a digital media lab.

Rex Peel started as a music teacher at Dyett in 2018 and taught beginner, intermediate, and advanced band and choir as well as a piano course until leaving his position earlier this year. “Dyett is special because it was a reopened school, and so they provided the funding so that it would succeed,” he said. “But I have worked for a number of other schools in CPS that did not have that.”

Mollison Elementary School is located in Bronzeville, just a couple of blocks from Armstrong (Lillian Hardin) Park, named after jazz musician, composer, and bandleader Lillian Hardin Armstrong. Bronzeville itself has a long history of producing legendary musicians, including Louis Armstrong and Nat King Cole. As a music teacher there, Peel described his class as “music on the cart,” where he would move from room to room with very few instruments.

At both Mollison, where he worked from 2016 to 2017, and William Bishop Owen Elementary School in Ashburn, where he worked from 2017 to 2018, Peel was the only music teacher.

The differences in access to elementary school art programs are stark between regions located on the North and South sides. During the 2020-21 school year, there were zero seats per hundred students for fine and performing arts in the Bronzeville/South Lakefront region. In Greater Lincoln Park, there were seventy, in the North Lakefront region, there were fifty-two, and in the Central Area region, there were fifty-three.

As a teacher at Dyett, Peel has felt the effects of lack of access to these programs in elementary school. “It’s very hard to develop sixty children who have never had a musical experience, even after four years, if there’s nothing laid at the beginning,” he said.

Nadine Smith is the only music teacher at Dyett now that Peel left. She started five years ago and has since taught choir and band. “At the elementary level is where students should be getting those foundational skills and should be able to walk into high school and be prepared to go to the next level.”

In a previous role as educational outreach coordinator for the Lyric Opera of Chicago, she visited schools on the North Side. “For some of the schools, i.e., Northside College Prep… you’ve got to be kidding me,” she said. “I thought I was walking in on a college campus when I walked into that school. Their strings department is extremely strong, and I mean just big, beautiful basses in a room designated for the arts, for music; their orchestra is just profound,” she said. “And I guess that poured kerosene on my desire to be able to see that also occur on the South Side of Chicago.”

In 2009, when he lifted the desegregation consent decree, U.S. District Judge Charles Kocoras stated in an opinion that within the district schools, “the vestiges of discrimination are no longer.” But more than a decade later, the district remains highly segregated. Black students in Chicago are disproportionately harmed by school closures, decreased access to quality schools, and the increasing privatization of Chicago schools.

Madeleine Parrish is the Weekly’s education editor. Chima Ikoro is the Weekly’s community organizing editor.

Amen ! Every well written word of TRUTH! I hope we are moving in the right direction this year!

As a south side CPS educator I have spoken about this for 40 years! We HAVE to do better! All our communities depend on it!