This investigation is the first in a series of projects that will document and explore public housing on the South Side. If you have tips or suggestions about coverage, email editor@southsideweekly.com.

This story is accompanied by a narrative comic about the CHA’s redevelopment of Bronzeville’s public housing.

For a glossary of terms used in this story, click here.

How is it that in the center of one of the nation’s largest cities there are empty fields that stretch for miles, isolated houses surrounded by vacant lots that have gone untouched for a decade or more? Why would a government agency whose mission is to provide housing for vulnerable citizens retain all this vacant land when it has plenty of surplus funding with which to build homes? Moreover, why would it do so at a time when the demand for housing among the city’s poor people is so great?

The undeveloped tracts along the State Street Corridor in Bronzeville are the silent legacy of the twenty-first-century Chicago Housing Authority. In this investigation, the Weekly attempts to tell the story of public housing in Chicago through the six housing projects that made up this corridor, a nearly continuous stretch of public housing that at one time ran from 20th Street in the South Loop to 54th Street in Washington Park. The CHA’s effort to redevelop these projects has been characterized by extensive delays and minimal construction, ultimately yielding a combination of unfinished mixed-income communities and vast stretches of neglected land. This redevelopment effort has been only one part of the CHA’s activity over the past twenty years, but its execution is telling of the agency’s priorities. Over the past decade, the CHA has redefined its approach to providing housing; along the way, some of its promises have been left behind.

HOW WE GOT HERE

The Early Years

The story of the State Street Corridor is not merely one of bricks and mortar: the whole saga is wrapped up in the political history of an agency that has long been criticized for an alleged lack of commitment to providing housing for Chicagoans—that is, to fulfilling its own mission. So in order to understand the current landscape of public housing in Bronzeville, one must start before the towers came down, when the CHA owned thousands of massive, dilapidated properties in Bronzeville and across the city. These projects were originally built during the fifties and sixties, when housing segregation was still more or less legal, and created isolated neighborhoods of poor African-American residents.

In May 1995, after decades of neglect, mismanagement, and corruption in the CHA, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) took control of the city agency with the intention of setting it back on course. Just four years later, then-Mayor Richard M. Daley brokered a deal with HUD to return the CHA to city control in exchange for a vow that Chicago would radically change its approach to public housing. The resulting Plan for Transformation (signed while Rahm Emanuel was vice chair of the CHA’s board) called for the demolition of nearly 18,000 units of neglected public housing and the construction or renovation of 25,000 units, all over the course of the following five to seven years. Accordingly, HUD and the CHA entered into a ten-year “Moving to Work” agreement that gave the CHA freedom to spend federal funding however it wanted in order to reach the goals of the Plan.

In the 1990s, the city had already begun to demolish some of its high-rise public housing as part of a HUD initiative called HOPE VI. The Plan for Transformation promised to expand and ramp up this initiative in Chicago. The CHA would knock down its clustered high-rise developments, increase its distribution of housing choice vouchers (HCVs), and undertake the construction of “mixed-income communities”—developments encompassing public housing units, “affordable” units for residents on federal housing assistance, and market-rate units. At the time, mixed-income developments were touted as a cure-all for the longstanding challenges of segregation and extreme poverty that dogged public housing in American cities.

The CHA demolished Chicago’s largest and most notorious projects—Cabrini-Green on the North Side, Henry Horner on the West Side, and on the South Side an extensive ecosystem of public housing that included the Harold Ickes Homes, Stateway Gardens, the Ida B. Wells projects, and the Robert Taylor Homes—in order to replace them with new mixed-income developments. At the time of their demolition, housing projects in Bronzeville alone provided homes for at least 30,000 residents on government assistance.

From the beginning, the demolitions were sold to residents as a necessary first step in the ongoing revitalization of their communities. Residents were promised that the overcrowded and crime-plagued high-rises would be replaced swiftly not just with new homes, but with vibrant communities. The creation of “community” has been at the center of CHA’s professed ambitions for its mixed-income developments; the reigning attitude toward housing at the turn of the century was that with a diversity of economic backgrounds in a community came a better quality of life and more upward mobility for lower-income families. As the CHA noted 2000, the Plan calls for “more than the renovation of public housing; it calls for broad community planning to revitalize entire neighborhoods.” Or as Mayor Daley put it in 2006, when the CHA had already missed its initial 2005 deadline for the plan’s completion: “We’re not just building homes. We’re building lives and building communities. And…we’re rebuilding souls.”

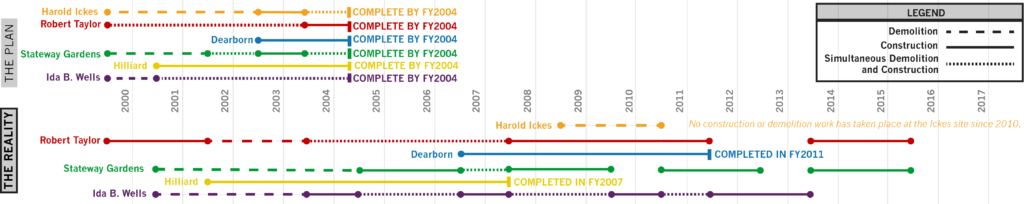

Demolition Without Redevelopment

At Henry Horner on the West Side, where redevelopment had begun in 1995 as part of the HOPE VI program, the CHA scheduled redevelopment construction to happen alongside demolition. This allowed residents to move out of their old homes and immediately into their new ones. No such timeline ever materialized for projects on the State Street Corridor, including Ida B. Wells, Robert Taylor, and Stateway Gardens. The CHA did not start redevelopment construction on the Corridor until most of the high-rises in each project had already been razed. Demolition proceeded on a delayed and less orderly schedule than had been set out in the original Plan: at Ida B. Wells, for instance, hundreds more units were closed and demolished in 2007 and 2008 than the agency had anticipated each year.

As the high-rises came down in the early 2000s, real estate prices in Bronzeville skyrocketed, based purely on speculation about what would happen once the high-rises were gone. Given the booming real estate market, the Daley administration would have expected that the fast-paced private development already happening in the South Loop would naturally extend into Bronzeville once the projects were gone. By replacing public housing high-rises with new, attractive market-rate housing, the CHA would help jump-start the process of gentrification. But the housing market crash dashed Daley’s (and developers’) hopes for large-scale revitalization—the recession stopped both the speculation and private investment in their tracks, and the CHA was left with the task of carrying out redevelopment in an area that was no longer up-and-coming.

After The Recession

To this day, the CHA uses the recession as a primary justification for the extensive delays in the construction timeline, even though the agency had fallen behind the original Plan’s timeline for redevelopment long before 2008. The CHAhas claimed that since its mixed-income developments are partially financed by banks and private equity firms, it became harder to fund them during a recession. But even this explanation, does not hold water: despite what the CHA says, private investment has provided little to none of the funding for existing mixed-income developments.

“The selling point that private financiers will help finance these mixed-income redevelopments is a flat-out lie,” says Leah Levinger, executive director of the Chicago Housing Initiative (CHI), a community organizing coalition that aims to empower public housing residents. “There are forty-three such redevelopments, and in no case is there significant investment of private resources.” Three-quarters of existing redevelopments received no private funds. In cases such as Savoy Square in the Robert Taylor redevelopment, private investment accounted for only two percent of the overall financing.

In the aftermath of the housing market crash, then, the agency still had the resources necessary to continue mixed-income redevelopment in Bronzeville. But even as the market has recovered, the CHA has continued to build far fewer units each year than it had before the recession. Critics like Levinger see in this trend not only evidence that the CHA is not committed to providing housing to Chicago’s vulnerable citizens, but also that the recession is not the cause of the agency’s slow construction rates. The Weekly sent the CHA a series of questions that included questions about the recession and the construction slowdown, but the statement it issued in response did not address these questions.

Housing By Other Means

Trends in the CHA’s activity in recent years seem to indicate that the agency is no longer as interested in pursuing new construction in the State Street Corridor—or anywhere else. In 2008, after the CHA was already a few years past its original deadline for completing the Plan for Transformation, HUD granted the agency an extension on its Moving to Work agreement. This extension promised to continue giving the agency broad spending freedom until 2018 so it could finish work on the Plan. But a key amendment made to this extended agreement in 2010 permitted the CHA to count project-based vouchers (PBVs) toward its overall goal of building or repairing 25,000 units of public housing. PBVs are vouchers that are restricted to one development—the CHA enters into contracts with private building owners and refers families from its wait list to fill vacancies in the building. PBVs are more restrictive than normal housing choice vouchers, because if a family leaves the specific PBV development they lose access to their housing voucher.

Since the amendment was added, these PBVs have accounted for more and more of CHA’s yearly unit delivery toward the Plan for Transformation, while actual construction on former public housing sites has accounted for less and less. Because of this qualification, the agency can now say that it has nearly reached its initial goal of 25,000 units (albeit almost a decade behind schedule) without even coming close to fully redeveloping the State Street Corridor.

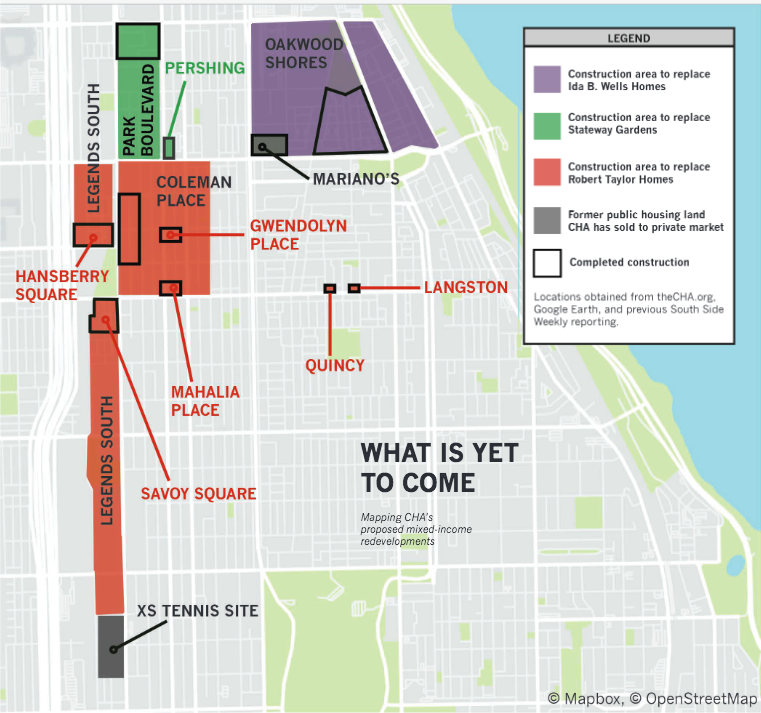

While the CHA’s yearly construction activity has decreased, it has also sold or swapped portions of former public housing land that were originally included in plans for mixed-income redevelopment. In three high-profile cases, the agency has let go of undeveloped tracts that were originally slated for redeveloped housing, each time arousing the anger of activists who say the agency is reneging on the promises of the Plan for Transformation. In 2014, before any formal plans had been released for the redevelopment of the Harold Ickes Homes, the CHA swapped almost one-quarter of the Ickes parcel with the City in exchange for the construction of a new athletic field for Jones College Prep, which is located in the Loop.

Also in that year, the CHA’s board approved the sale of a parcel of Ida B. Wells land along King Drive for the tax increment financing (TIF)-subsidized construction of a new Mariano’s grocery store; as part of the deal, the development reserved around one-third of jobs in the grocery store for former Ida B. Wells residents.

Also in 2014, the CHA sold the southernmost portion of the Robert Taylor Homes site to XS Tennis for the construction of a massive tennis facility and athletic center; the purchase was again subsidized by the city through $2.9 million in TIF funding. And no type of redevelopment construction has occurred at all on the Robert Taylor site south of 45th Street.

“After a while you start to say, ‘This is just the reality, they’re not going to rebuild,’ or that if they do rebuild, it’s not going to be for us,” says Rod Wilson, executive director of the Lugenia Burns Hope Center, which, along with organizations including CHI, has agitated for the CHA to fulfill its redevelopment promises in the face of these land swaps and sales.

These changes in the CHA’s actions represent a shift away from the construction promised in the Plan for Transformation and toward a new understanding of what it means to provide “housing” to a city in need. The CHA now primarily provides housing vouchers to an overstuffed wait list and maintains its existing stock of senior housing and small family developments. At the same time, it has retained a large funding reserve and gradually divested itself of its larger properties, selling land it could have used to build new housing. In a phone interview with the Weekly, Molly Sullivan, director of communications for the CHA, expressed almost exactly these sentiments, stating that while the CHA remains committed to fulfilling the reconstruction promised in the original Plan, building housing is no longer the agency’s top priority.

“Housing is important, but just putting a new roof over people’s heads will not help public housing families become part of Chicago’s economic and social mainstream,” the agency said in a statement to the Weekly. “CHA’s commitment to building sustainable communities and ensuring residents have access to jobs, educations, training and other opportunities is at the forefront of our work as we move toward meeting the goals of the Plan for Transformation.”

WHERE WE STAND

The Real Need

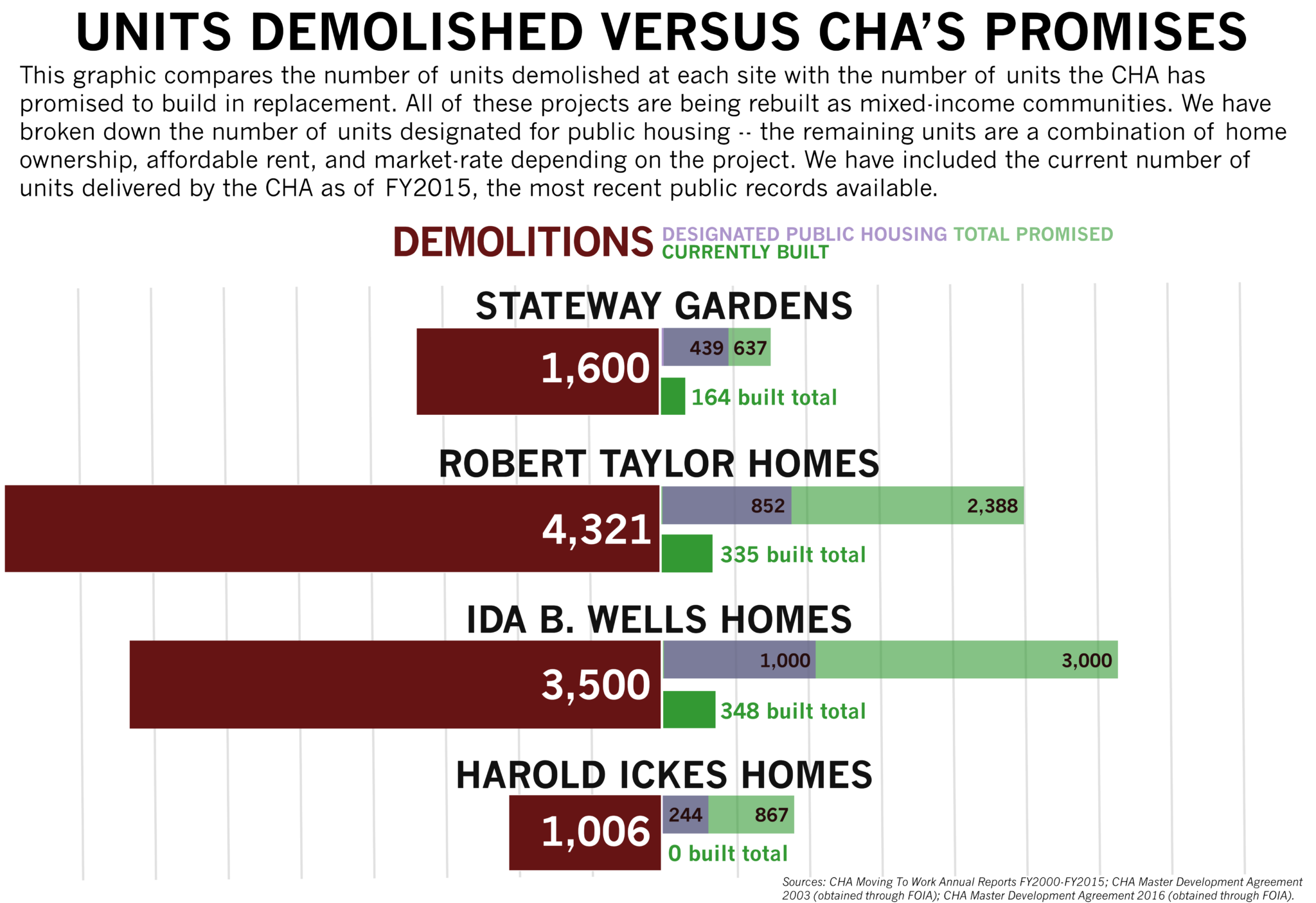

Our analysis of redevelopment on the State Street Corridor—which includes Harold Ickes, Robert Taylor, Stateway Gardens, Hilliard, and Dearborn—and at Ida B. Wells found that construction is behind schedule by more than a decade, and that many of the completed redevelopment phases have fallen below expectations and failed to meet promises made at the outset of the Plan for Transformation. Reading through the agency’s many annual plans and reports reveals that over time the CHA has gradually lowered expectations while routinely missing yearly deadlines and benchmarks set both internally and by HUD.

But the significance of these long delays is only fully clear when seen in the context of the agency’s overall failure to be proactive in providing housing. Our comparison of the proposed redevelopment timeline to the actual timeline and of proposed construction to actual construction shows how far the CHA has fallen short of meeting its own goals, but in order to see how far the agency has fallen short of providing sufficient housing to Chicagoans, it is necessary to look beyond the agency’s numbers.

Before Jamie Kalven founded the Invisible Institute, a journalism nonprofit advocating for police transparency, he reported on life in Stateway Gardens for decades. He believes the numbers the CHA used at the outset of the Plan for Transformation are “essentially false,” little more than a “shell game”—they vastly underestimate the need created by the Plan for Transformation demolitions. When the agency estimates the number of families who were displaced from the torn-down projects, they work from occupancy numbers as of October 1999. By this point, Kalven says, the agency had already driven down occupancy for years by vacating derelict units without rehabilitating them and moving in new residents.

The original 25,000-unit goal of the Plan for Transformation only includes the construction of about 8,000 new units of public housing (the rest of the work is on senior housing and renovation of existing projects). The CHA’s estimate of the number of families who were displaced from high-rises is similar, at around 8,300. But according to CHA reports, nearly 18,000 hard units of public housing were demolished as part of the Plan for Transformation. In that 10,000-unit discrepancy between demolition and reconstruction, says Kalven, is an invisible population that has never been on the CHA’s books. The agency had forced down occupancy of the high-rises and Wells for years by vacating dilapidated units without rehabilitating them and moving people back in. When they took stock of the displacement caused by the demolitions, they did not account for the considerable number of transient individuals and families who used vacant units as last-resort housing.

The CHA told the Weekly in a statement that as of the end of 2016, only 2.9 percent of displaced residents who have a right of return to the CHA’s system have not yet satisfied that right. But the other ninety-seven percent contains a few key populations: it includes not only those who have chosen not to return to the CHA (meaning either to live in a public housing unit or receive a voucher), but also deceased and evicted residents and the nineteen percent of residents who have lost their right of return by not responding to the CHA’s attempts to reach them. The agency’s own 2011 update on relocation found that thirteen percent of families who lived in family housing in 1999, some 2,200 families, “had not responded to outreach”—in other words, their whereabouts could not be confirmed.

It is wrong, then, to accept the CHA’s Plan for Transformation promises as reflective of the need created by the high-rise demolitions, or to believe that completion of these goals will address some meaningful portion of the overall demand for housing in the city. This need, to the extent that it is measurable based on the CHA’s numbers, seems to be higher than ever, and is far from being met by the CHA’s current services. When the agency opened 40,000 new spots on its voucher waiting list in 2008, for the first time in several years, more than 232,000 families applied for a spot. The list opened again in 2014 and over 282,000 families, or more than a quarter of Chicago households, applied for a spot; it now stands at more than 119,000 families. And while the wait list expanded, the CHA bulked up its liquid reserves to almost $400 million and paid off its pension fund using federal money that was supposed to be spent on housing vouchers for people on that very list.

Mixed-Income Communities So Far

Even if the CHA defends widespread voucher usage as a better and more humane way to provide housing, it promised displaced residents of the demolished high-rises not just a home somewhere in the city, but a community. In some places, like Horner, that community was at least partially preserved, but the mixed-income redevelopments of Oakwood Shores (formerly Ida B. Wells) and Legends South (formerly Robert Taylor Homes) are far from complete “communities.” Kalven called them “prospective ghost towns”: the units may be new, but residents who live in them are surrounded by still-undeveloped fields, and private developers have invested little in retail or social services around the CHA’s new residential construction, perhaps in part because Bronzeville’s housing market has been slow to recover since the recession. This contrast might be most visible at the Park Boulevard development (formerly Stateway Gardens), where across from a mixed-income apartment block at the corner of Pershing Road and State Street sits the boarded-up back of Crispus Attucks Elementary, closed in 2008.

Wilson, of the Lugenia Burns Hope Center, notes that after the housing market crash, many market-rate residents in the CHA’s new mixed-income developments were angry that the value of their homes had plummeted, essentially freezing them in place in a neighborhood where private investment had halted.

“I think if they really wanted to develop these communities, they’d put more resources into the schools and reduce the crime,” says Wilson. “[Those are] the biggest dictators of where people want to live, by far. If you fixed those, you would see a more organic version of ‘mixed-income.’ ”

The failure of these developments to become the gardens of Eden envisioned at the outset of the Plan has been well documented, including in a recent book from the University of Chicago Press, Integrating the Inner City, whose authors Robert Chaskin and Robert Kuster called mixed-income housing a “relatively narrow policy intervention” and noted that “the enthusiasm for it ought to be tempered by the experience we’re having” with finished developments in practice—which is less than to promising, to say the least.

“Chicago has a warped sense that development is about replacing populations, taking out the low-income and replacing it with more affluent people. And then you put up all these shops and say, ‘Look what we’ve done,’” says Wilson. “Well, you didn’t improve the quality of life of the people that were there, you just kicked them out.”

The recession may have prevented continued private investment in areas around the State Street redevelopments, but the long delays on the completion of these developments themselves have all but destroyed the tight-knit communities that once occupied these areas, even if some residents have had or may someday have the chance to return. By now, says Wilson, many former residents of these projects have given up hope of ever moving back, or of being able to convince the CHA to be more proactive about construction.

CONCLUSION

In a statement to the Weekly, the CHA said it remains committed to redeveloping what remains of the vacant land:

“CHA’s commitment to the communities along the State Street corridor remains the same today as it did in 2000: To create strong, vibrant mixed-income neighborhoods where residents are connected to the larger communities around them and have access to amenities, jobs and education that they need and deserve.”

But skeptics may only have the agency’s word to go on in evaluating this claim After the publication of a report by the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability (CTBA) exposing the agency’s failure to spend federal voucher money, the CHA upped its voucher usage to meet the ninety percent usage rate suggested by HUD. Without explaining the significant reserve buildup also charted in the CTBA report (the agency’s liquid reserves peaked at $471 million in 2011), the CHA said in a statement to the Weekly that it had spent down its reserves to $154 million by the start of 2016.

But Daniel Hertz, Senior Policy Analyst at CTBA, said that number represents only a portion of the CHA’s working capital. He explained that in the quarterly report from early 2016 where the CHA claims to have $154 million in reserves, the agency acknowledges that the number does not include “a HUD‐allowed operating reserve of $117M that the agency intends to use for future capital expenditures.” But the agency’s most recent audited financial disclosure document, from the end of 2015, lists the agency’s working capital reserves at $379 million, a full $100 million more than it claims to have in the quarterly report. Hertz said neither he nor other analysts of the CHA’s finances understand how the agency arrives at that number.

“We’ve been unable to reconcile the numbers in CHA’s audited financial documents with the numbers in their quarterly reports, which don’t have to be audited by outside financial experts,” he said.

To make matters worse, the agency will soon have even less oversight on its spending than it has ever had before. A federal law signed in 2015 required HUD to extend the “Moving to Work” agreement again to 2028 without actually incorporating requirements about how much federal money the CHA must spend. In an updated report released earlier this year, CTBA cited this fact as cause for concern that the CHA will not continue to spend federal money as proactively as it has in the past two years. Moreover, HUD under the Trump administration will likely govern with far less regulatory rigor than the Obama administration did, meaning there will be far less federal scrutiny on the CHA’s spending.

It seems doubtful, given the CHA’s present priorities, that the trickle of mixed-income construction along the State Street Corridor will ever result in fully redeveloped communities. The agency’s plans for this year do indicate that it will pursue more mixed-income construction soon—there are provisions for development at Harold Ickes, Stateway, and Legends South There is no telling, however, when exactly these plans will result in the construction of new homes. Until they do, the fields along the State Street Corridor are not only testaments to the displacement and erasure caused by the Plan for Transformation, but also reminders of its promise—a promise that is still, after almost twenty years, somewhere between unfulfilled and broken.

POSTSCRIPT: THE RENOVATED PROJECTS

Renovating the Hilliard Homes

The Hilliard Homes, designed by the renowned architect Bertrand Goldberg (most famous for the “corncob” Marina City towers in the Loop), are one of two State Street Corridor developments that were not razed as part of the Plan for Transformation. Originally built as public housing in 1966, the high-rise development contains two towers for seniors and two towers for families. By the 1990s, it had fallen victim to the same problems as the rest of the city’s public housing, but its status as an architectural landmark saved it from demolition. Instead, the building was placed on the National Register of Historic Places and became eligible for funding from a variety of public and private sources. The redevelopment effort, initiated in 1999 by real estate developer Peter Holsten (called an “anti-gentrifier” by Crain’s for his commitment to building affordable housing), cost $98 million and finished in 2006.

In a story published in the Chicago Reader last October, Maya Dukmasova undertook an in-depth exploration of the history of Hilliard and its redevelopment. The new mixed-income Hilliard, she concludes, has largely been a success, thanks in no small part to Holsten’s belief that attentive, charitable management—something missing from the old CHA—is key to a housing community’s success. But the article also questions whether Hilliard’s strict set of resident guidelines—9pm curfews in the park, required cash deposits for using the community room—is necessary for the maintenance of a mixed-income development.

Renovating the Dearborn Homes

The Dearborn Homes are the only State Street Corridor project that was neither razed nor remade as a mixed-income development as part of the Plan for Transformation. It is still operated solely by the CHA and consists entirely of public housing residents; according to a Chicago Reporter investigation, the project’s census tract had the highest concentration of “deep poverty” in the city, at nearly fifty percent. The project avoided demolition because it passed a test mandated by a 1996 HUD funding bill: according to the bill, CHA was required to demolish all public housing units that could not be renovated for less than the cost of a typical housing voucher. More than forty percent of the agency’s housing stock failed this test, but the low-rise Dearborn Homes did not.

CHA renovated the project in five phases from 2007 to 2011, performing a gut rehab on each of its sixteen towers and installing new water, heating, and electrical systems. The exterior of the towers also got a makeover, with classical decorations added to the once-bare walls and roofs. Vacant units and storage rooms were combined with existing apartments to bring the project’s original 800 units down to 660. The five construction phases of the renovation effort cost a total of $136,627,018, according to contracts from a Freedom of Information Act request.

Two longtime Dearborn Homes residents who spoke with the Weekly about the renovation said it had been, in large part, a success, and that the water and heating had become functional again—before the renovation, they said, there had been routine flooding in some of the buildings on the western side of the project. But one of these residents, Etta Davis, noted that quality of life in the projects had been most improved by the added presence of closed-circuit cameras and security guards who now monitor the building’s entrance.

Of the four building contractors employed by the CHA for the job, at least two have previously come under fire for their work with public housing. The CEO of Burling Builders, Elzie Higginbottom, was exposed by the Sun-Times for essentially giving his own construction company a contract while he sat on the board of the Housing Authority of Cook County. Walsh Construction, responsible for two of the five Dearborn renovation phases, was sued for discriminatory hiring practices by residents of the Altgeld Gardens housing project during the company’s renovation of that project.

GLOSSARY OF PUBLIC HOUSING TERMS

Housing Choice Vouchers (HCVs)

Program that allows low-income families to rent a house or apartment in the private market in Chicago; the CHA uses federal funding from HUD to pay landlords the cost of a family’s rent. Families are selected for this program via a lottery that picks from the CHA’s voucher waiting list at random; the waiting list is currently closed to new applicants and has been since 2008.

Project-Based Vouchers (PBVs)

Housing vouchers that are tied to a specific building or development; the CHA enters an agreement (these can last anywhere from five to thirty years) with a development owner and refers interested families from its HCV waitlist to that specific development. If the families leave the development, they lose their housing assistance. Notably, PBV units do not cover as much rent as the CHA’s typical public housing units do.

Mixed-income development

A development that contains some market-rate units, some affordable housing units (units for lower-income families, subsidized for developers by the national Low Income Housing Tax Credit program), and some public housing units (units for low-income families whose rent is subsidized by the CHA).

Public housing

Housing assistance provided by the CHA to families who make under thirty percent of the median annual income in Chicago.

Affordable housing

Housing assistance provided through federal government programs to families who make anywhere between thirty and eighty percent of the median annual income in Chicago.

Market-rate

Housing with rent that is dictated by the real estate market; people who live in these units do not necessarily receive government assistance to pay their rent.

“Moving to Work”

An agreement made between the CHA and HUD that gave the CHA upward of a billion dollars in block grants to spend on completing the goals of the Plan for Transformation. This agreement has been extended twice, first to 2018 and then to 2028.

HOPE VI

A national program established by HUD in the 1990s that awarded housing agencies grants to demolish high-rises and replace them with mixed-income housing.

High-rise housing

Many of CHA’s largest properties were high-rise towers that housed hundreds of large families in close quarters. These properties were widely considered the most impoverished and dangerous of the city’s public housing projects.

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.

THIS IS A GREAT STORY! WE NEED TO SEE MORE LIKE THIS!

Wow! This report is exhausting, the result of excellent and thorough investigating! CHA should be the entity giving the public regular updates on their ‘Plans For Transformation’! Thank You!

This is the same situation happening in Denver Colorado. Crooked politics is destroying the traditional quiet and safe ways Coloradoans live. The rich are moving in and the poor are kicked out. We need professional researchers and journalists to expose what is happening here in Denver Colorado.

I lived in Dearborn homes after the rehab 2008 it was very nice and for the first time in memory a decent place to live with my kids.

After 2015 the place went back into decline and crime and gangs moved in took over the hall ways and parking lot , swing sets and park.

The Chicago Housing authority CEO Eugene Jones and Chairmen John Hooker should be replaced Because they seem to be corrupt and into giving their friends CHA contracts at the expense of CHA residents.

Great article.

One point that really stood out to me was the Dearborn Homes renovation cost—$136M for 660 units is over $200K per unit! As a Chicago real estate investor with renovation experience, that sounds astronomical to me.

I would love to see a breakdown of that budget. Seems fishy, especially given the less-than-stellar reputations of some of the contractors involved.