Faculty and staff at Chicago State University (CSU) have suspended their strike, pending an offer from the administration, after being on the picket line for ten days and orchestrating a sit-in at the university president’s office. On April 3, CSU staff went on strike for better pay, more manageable workloads, and other improvements to their working conditions, and on April 16 they announced a tentative deal, pending a vote by the union later this week.

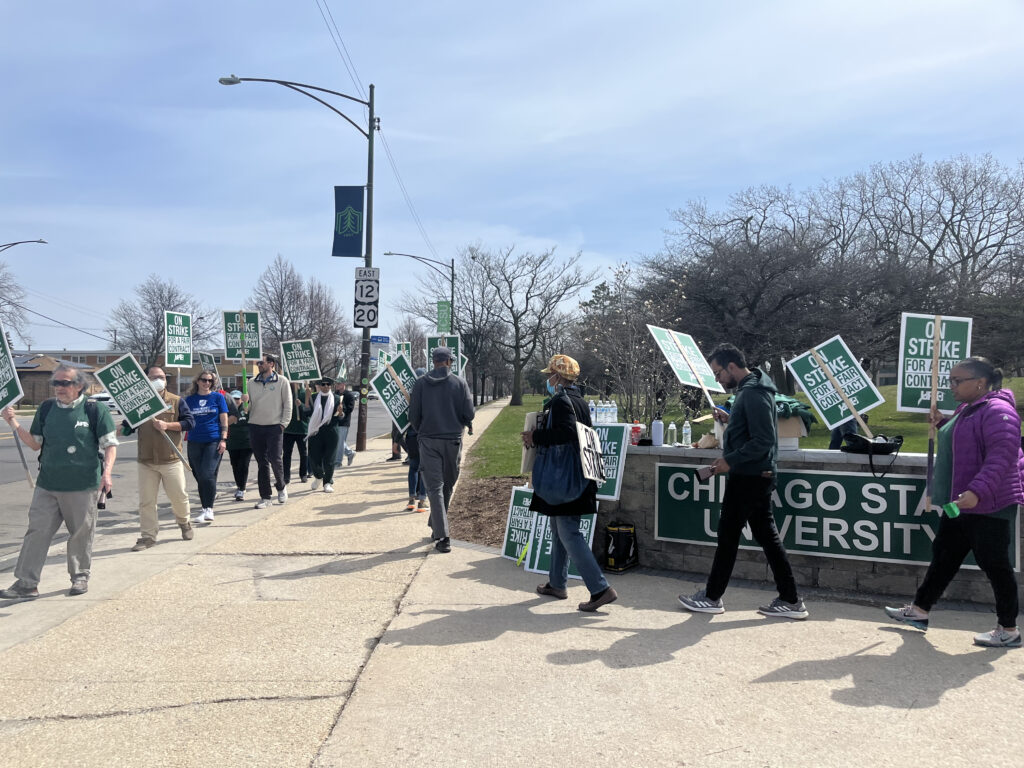

A week into the strike, on a bright Monday morning at the intersection of E. 95th St. and S. King Dr., people filed into the picket line ringing green cow bells and holding signs. About a hundred professors, staff, alumni, students, and supporters marched in a circle in front of a waist-high stone wall displaying a Chicago State University sign.

McFadden & Whitehead’s 1979 disco classic “Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now” could be heard over the speaker, echoing the sentiment that brought everyone to the picket line that day: “If you’ve ever been held down before, I know you refuse to be held down any more.”

The union had been bargaining with the administration over a new contract for ten months, but negotiations stalled over several key points. Many faculty saw the administration’s unwillingness to negotiate further as part of a pattern of disinvestment, as CSU workers have faced the brunt of state budget cuts at public universities. “It feels like every time you’re on the South Side, you have to beg for, you have to fight for, everything that others just can simply negotiate and get,” said Dr. Ernst Coupet, an economics professor on the bargaining team who has worked at CSU for twenty-two years. “I’m just tired of that.”

Holding a megaphone and welcoming in each new supporter, statewide president of University Professionals of Illinois (UPI), John Miller, was among those leading chants like “Equity and justice!” which was fervently answered by the crowd with “for CSU!” The chants harmonized with clinking bells, music playing on speakers, and intermittent honks from trucks and cars showing their support. “What do we want?” the marshalls asked. “Contract!” replied the crowd. “When do we want it?” “Now!”

Following a few hours of marching on Monday and whispers of a special guest, Mayor-elect Brandon Johnson visited the picket line to express solidarity with the union. An educator and long-time organizer with the Chicago Teachers’ Union (CTU)—which also expressed their solidarity with CSU—Johnson was immediately comfortable, hugging and greeting people as he made his way through the crowd.

In his speech, he acknowledged how vital CSU is to the city: “This is an incredible institution that has a long history of pumping out some of the greatest minds to actually deliver services for the city of Chicago.”

Representing about 160 faculty, lecturers, academic support staff, and technical support specialists at the university, the CSU union chapter is part of the UPI Local 4100, affiliated with the American Federation of Teachers (AFT). The union began bargaining over a new contract with the administration in June of last year but negotiations eventually stalled. In March, the union overwhelmingly voted (ninety-eight percent) to move forward with a strike and filed their intent to strike with the Illinois Educational Labor Relations Board.

CSU faculty are among the lowest paid public university faculty in the state: CSU lecturers have the lowest average salary of any Illinois state university, and CSU professors make the second lowest average salary, according to data from the Illinois Board of Higher Education (IBHE). CSU staff have effectively been forced to take a pay cut in recent years, according to Coupet. While the average faculty salary in Illinois is $95,670, according to a report from the National Education Association (NEA), the average full-time teaching faculty salary for CSU in 2021 was about $84,640, with full-time lecturers making as low as about $37,000.

According to the union, average annual raises for faculty at CSU over the past five years were only between zero and 2.75 percent, but because of inflation, Coupet estimates that CSU staff have lost 1.45 percent annually in real wages. In real buying power, a CSU worker’s salary before the recent agreement was only worth eighty-five percent of what it was worth in 2016.

To bring salaries in line with other public university faculty, the union proposed annual raises from four to 6.5 percent over four years, totaling $523,000 or $131,000 annually. The administration countered with raises between 2.5 and three percent and a $1,000 lump sum payment, according to the salary proposal released by the union Friday prior to the agreement. Faculty pointed out that the administration could have paid for this part of their proposal with president Zaldwaynaka “Z” Scott’s new contract and bonuses totalling an estimated $500,000 or the $480,000 CSU spent on law firm Laner Muchin Ltd. to handle negotiations despite having general counsel on staff, according to the union.

Laner Muchin is also representing two other public schools, Eastern Illinois University and Governors State University, who went on strike after CSU.

The union also fought against CSU’s family leave policy and faculty workloads. Currently, if both parents or caregivers work at the university, CSU only allows one parent to have paid family leave. According to Coupet, the union was adamant that each person fostering or having a child should have the right to paid leave.

The union also pushed back against increased faculty workloads produced by a credit system that assigns more courses to teachers with smaller class sizes and a system that does not adequately factor in research as part of a professor’s workload yet requires research for retention.

CSU did not respond to a request for comment by publication time.

While increased pay and better teaching conditions are important, the crux of this fight was always much bigger for the faculty, staff, and students involved. “I think a lot of times people think the strike is about just what we get paid. And that’s important; a living wage is important to be able to do your job successfully,” said Dr. Kelly Ellis, an English professor who has worked at CSU for twenty-four years. “It’s also about the history and culture of diminishing certain schools, and not others.”

Over the years, CSU faculty have weathered budget impasses, administration turnovers, shortened school years, threats of layoffs, years without raises, and so much more. When adjusting for inflation, CSU’s budget has dropped by thirty-three percent since 2004.

When Illinois’s public universities suffered cuts in their allocations, CSU was hit with the largest funding cut of any other school with allocations, dropping by about sixty-five percent from 2015 to 2016. Despite CSU relying on state funding more, it experienced a substantially bigger drop (by about seventeen percent) than any other public university in the state. As a result, CSU laid off about 400 non-faculty members and later about ten faculty members.

CSU is the only public university on the South Side of Chicago and the first university in Chicago to accept Black students. For years, CSU has primarily catered to Black, Brown, and working class students. In fall 2022, about seventy percent of the 2,300 undergrad and grad students were Black, more than any other public school in the state. And sixty-four percent of undergrads and sixty-seven percent of grad students receive some Pell Grant funding. That’s about double the national average.

“When it starts to become a habit that we are some of the lowest funded…then it’s time to step up,” said Ellis, who has gone to nearly every picket.

At Monday’s picket, Johnson pointed out that professors and staff are not just educating—they are providing vital support systems for their students. “Every single day you’re not just educating, you’re loving and supporting, and you’re building families…that’s what this movement is about,” Johnson said.

The students know this as well. Both Ellis and Coupet saw their current and former students on the picket line every single day, and they said students even assembled their own pickets. “Some of the students have been out as long as any faculty members have been out there. That’s how connected we are to our students,” said Coupet.

Over the past year, the union members said they often felt like the administration hindered negotiations by changing up or creating their own rules. According to Coupet, the administration would flat out deny requests the union brought to the table without providing reasoning for the denial.

Instead of working with the union representatives to guide them toward something mutually agreeable, he said the administration created a sort of guessing game. “They [would] treat us as if we’re supposed to guess how much money they have in their pocket, and they’ll let us know when it’s there….this is not really bargaining in good faith,” he said.

In response to the strike, the administration denied faculty accrual of vacation, sick leave, and other earned benefits and, on April 14, denied them their first paycheck. The administration was also poised to stop paying its larger portion of health insurance premiums had the strike lasted through the end of the month, leaving workers to pay to retain their coverage.

Last Friday, the day after President Scott briefly attended a bargaining session for the first time and refused to answer questions from faculty, union members held a sit-in at the president’s office. It ended in her office calling the campus police on the sitting protestors—her own staff and faculty.

Following at least eight long bargaining meetings over the course of the ten-day strike, the union and administration finally reached a tentative agreement. On Sunday, following the sit-in, the CSU administration responded to the newest proposal from the union. The bargaining team spent the whole day responding to the administration’s counter offer and finally agreed to a tentative contract after another four-hour meeting. In a statement released Sunday evening, the CSU union president, Valerie Goss, said they secured an agreement that increased staff and faculty pay while “recognizing the university’s financial constraints.”

Even though the strike has been suspended, it took an immense emotional and physical toll which, according to Ellis, also affected their students. “Not only am I concerned about their work, but I miss them. I like them. And most of my colleagues that I know feel the same way,” she said. “To get to this point is very difficult for us… But we’re doing this not only for ourselves but for the school and for future faculty.”

CSU faculty returned to class on Monday, April 17, following the tentative agreement. In her statement, Goss said that the staff and faculty have prioritized students’ needs since day one, so a return-to-work agreement was essential to reaching a final contract. To account for missed class time, the agreement includes extended office hours, tutoring sessions, registration meetings, exam sessions, and other services.

The exact details of the four-year agreement will be released once union members vote to finalize the contract later this week.

But for Ellis, the strike was successful in more ways than one: It built power and community among CSU staff, faculty, students, and other community members. “It’s been stressful. At times, it’s been frustrating. It has also been empowering, coming together with my colleagues and being united in what we’re asking for,” she said.

“So that has made me feel very powerful and made us feel very powerful.”

Savannah is a fact-checker and writer with the Weekly.