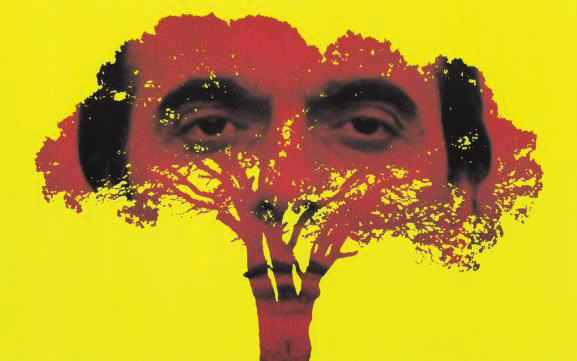

Is it ever okay to not feel sympathy for a suicidal person? This is one of the main questions explored by Abbas Kiarostami’s 1997 film, “Taste of Cherry.” Shown February 17 at the Logan Center for the Arts, the film was the finale of the “Death by Cinema” series, organized by UofC visual arts professor Karthik Pandian. “Taste of Cherry” follows what might have been the final days of a man named Mr. Badii (Homayoun Ershadi) as he drives around Tehran looking for someone to bury him. The grave is pre-dug—all he has to do is find this person and kill himself.

Beyond this, we know nothing about Mr. Badii; not his first name, nor why he wants to kill himself. Mr. Badii scares off all potential candidates for the job except for a taxidermist who fails to convince him not to go through with his plan. Mr. Badii ends up in his grave at the end of the movie, preparing to die.

At the screening, the audience barely filled the first three rows of the theater. This intimacy contrasted with the film’s long shots of the Tehrani landscape, which seem to be endless and empty in its half-built (or half-deconstructed) state. The faculty panel that followed touched upon the distance and the impersonality of Mr. Badii. Pandian revealed that the scenes in which Mr. Badii and his passengers converse in his car were shot one-half at a time, so Ershadi never filmed scenes with other actors; Kiarostami sat in the car with him and read the passengers’ lines. The disconnect created by this technique could be felt in the theater. “The viewer identifies with the passenger,” an audience member commented. “We feel their anxiety because we don’t understand Mr. Badii; there is nothing concrete shared between us.”

Maybe we would have felt more involved in Mr. Badii’s fate if he had been a character we could connect with. But even as he lay in his grave at the end of the film, nobody in the audience seemed invested. As he lay there, the night enveloped him. But this was not the end of the movie. A new scene unfolded: a glimpse behind-the-scenes, grainier and more pixelated than the rest of the film. Everything was green and alive, with actors and film crew interacting and joking around. And there stood Ershadi on set, speaking to others; by seeing “Mr. Badii” engaging with them, we could finally empathize with him. The audience members were awoken from the trance of the winding mountain roads. They looked around at others in the cinema, overcoming the jarring difference of this scene, finally eliminating the distance between the audience—the film’s passengers—and Mr. Badii; finally seeing something within him they could connect to.