Residents of a South Shore apartment building were jolted awake late at night last week when nearly 300 federal agents, backed by helicopters and flashbang grenades, stormed their homes in a massive immigration raid.

A video posted to social media by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) portrayed the raid at 7500 S. South Shore as a military-style operation to capture young brown men. In reality, federal agents detained nearly every resident of the 130-unit building—including children and babies—placing them in zip ties and separating them by race into vans for more than two hours early Tuesday morning.

In video footage from NewsNation, whose camera crew was invited to join the raid, masked agents are shown surrounding the building wearing green uniforms, with vests and yellow lettering spelling out “U.S. Customs and Border Patrol”.

Some officers pointed handguns equipped with tactical lights at the building; others held long rifles and wore helmets equipped with cameras and lights. Helicopters hovered in the sky, and agents on the ground threw flashbang grenades. Hastily awakened residents were only given a few seconds to open before agents broke doors down and forced their way inside, according to recordings by residents witnessing the raid.

In the NewsNation footage, agents appear to cut and damage a fence on Chicago Public Schools (CPS) property before using it as an entryway to detain people and move them into the school lot, which became an impromptu parking and staging area for the immigration operation.

In an interview with NewsNation, U.S. Chief Patrol Agent Gregory Bovino said that U.S. citizens were also detained during the raid due to safety reasons, saying “we generally don’t determine alienage while in the building,” adding, “no rights have been violated today.”

Masked agents made people line up outside the building, where they asked each resident their name and country of origin before lifting their shirt to check for tattoos. They proceeded to ask people if they had documents that proved they resided in the U.S. legally. One by one, building residents, including Black U.S. citizens, were loaded into vans where they were questioned further.

According to a DHS statement, thirty-seven people were arrested, including four children. As of this reporting, neighbors have still not been able to locate all the people who were arrested.

Neighbors reported that the raid began around 12:30am and lasted until about 4:00am on Tuesday morning. Videos posted on the Citizen app show that Chicago Police Department (CPD) officers were nearby, which the department later confirmed in a statement to the Weekly. Residents who spoke to the Weekly said they saw CPD officers blocking traffic near the building hours before the raid began.

An Invisible Institute reporter arrived at the building around noon Tuesday, hours after the raid. Entering through the open front doors, she found no residents inside.

The building had the appearance of longstanding neglect. The rancid odor of mold blended with the stink of rotting garbage and urine. Water leaked almost everywhere, and extension cords snaked along the halls and into apartments where residents had been siphoning electricity. A three-person cleaning crew mopped up standing water in the first floor hallway.

The elevator was broken; the stairwell had a putrid smell. Upstairs, the stench got stronger. Every door was kicked down or ripped from its hinges, leaving freshly splintered wood in the doorjambs. Inside, mattresses were flipped over, clothing and toys were scattered, and lamps were knocked over.

Back outside, an NBC reporter spoke with a resident who said he’d been detained for two hours. Behind the building, two workers were tossing belongings in the trash. A giant teddy bear lay in the dumpster.

Veronica Castro, deputy director for the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights (ICIRR), described what her team saw when they arrived at about 1:00pm on Tuesday.

“The condition of the building was really, really difficult to see,” she said. “It wasn’t being serviced. There were water and electrical issues and doors that were kicked in, and to the point where you couldn’t tell whether that was from the enforcement incident that had happened earlier that day, or if that’s the way that it was. We saw cribs and decorations for birthdays that were just left there by the folks that were taken in the middle of the night.”

The building was purchased by Wisconsin-based investor Trinity Flood in January 2020, according to Cook County records. On October 1, the day after the raid, a judge reviewed an emergency motion from Wells Fargo seeking to appoint Matthew Tarshis of Frontline Real Estate Partners as the property’s receiver.

Flood purchased three multifamily properties in South Shore in 2020. The neighborhood, which had the highest number of eviction filings in Chicago from 2015-2019 according to the Law Center for Better Housing, has seen a rise in outside real estate investors since the 2017 announcement of the Obama Presidential Center’s construction in the neighboring Jackson Park.

Wells Fargo Bank foreclosed on the building in mid-2024, bringing a $27 million lawsuit against Flood for missed loan payments. In late 2024, the City began closing its largest migrant shelters and, through state funding assistance distributed via Catholic Charities and moving support from New Life Church, relocated many families to buildings such as this one.

The Real Deal, a real estate news outlet, reported that City inspectors visited the building two weeks before the raid. Ald. Greg Mitchell (7th Ward) did not return the Weekly’s request for comment.

Credit: Caeli Kean

President Donald Trump’s administration has intensified immigration enforcement in Democrat-led cities with sanctuary laws like Chicago, carrying out operations that have grown increasingly militarized in scope and execution.

“The same administration that bussed them here is the same administration that is hunting them down to deport them,” said Castro, referring to Texas Gov. Greg Abbot, a Republican who sent thousands of migrants who were granted asylum by the federal government to Chicago in 2023. “There is a pretty large pocket of Venezuelans in the South Shore area. Many of them were applying for some kind of adjustment of status, whether it was asylum or other things …. They were trying to adjust through the guidelines set by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services [USCIS].”

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) said on October 1 that it had arrested more than 800 people since the launch of Operation Midway Blitz on September 8. It is not clear how many of those people had a criminal record or a signed judicial warrant, and how many were swept up in random detentions and car stops. According to Syracuse University’s data transparency project TRAC, which publishes federal enforcement statistics, 71.5 percent of the people currently in immigration detention have no criminal history.

In a motion filed in March, and a federal court notice filed in September, the National Immigrant Justice Center (NIJC) and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Illinois accused ICE and DHS of violating a consent decree on warrantless immigration stops when they detained and arrested dozens of people, including U.S. citizens, during recent immigration enforcement actions in Chicago.

“There has always been a fear that, because…the government had their information and because they were receiving support, that they could be targeted by this administration,” Castro said. “That fear was realized when [the federal agents] showed up looking for folks.”

Eboni Watson, a neighborhood resident who filmed the hours-long raid of the apartment building, told the Weekly she had just gone to bed and closed her eyes when she heard a loud ‘bang’, followed by the distinct buzzing of drones, a sound she had come to recognize after noticing them hovering near her home for the past three or four weeks.

A moment later, Watson’s phone lit up with a notification from the Citizen app that said there’d been a car accident outside. The buzzing grew louder. She grabbed the phone and got out of bed to look out the window.

Buses Rerouted for ICE Activity, Flashbang Mistaken for Shooting @CitizenApp

2658 E 75th St Sep 30 1:18:19 AM CDT

Agents were everywhere: some were running down the street while others jumped out of Budget rental vehicles. Above the building across the street, agents rappelled from helicopters. Watson counted the flashing lights of nearly ten hovering drones, and saw men on rooftops farther down the block. Also awoken by the commotion, some of Watson’s neighbors had gathered in their yard. They were soon approached by masked militarized police. At that point, Watson went outside, where she saw agents had flooded the entire block and surrounding area.

“You could see guys with FBI, ATF, DEA jackets and vests on,” she said. “You could see plainclothes officers. You could see Chicago [police] was out there blocking off traffic, redirecting traffic, helping them—and they are not even supposed to coordinate with them.” Chicago’s Welcoming City Ordinance prohibits CPD from assisting ICE with immigration arrests, but the department has maintained that it can direct traffic and police protesters near immigration activity for public safety reasons.

In a statement, a CPD spokesperson said they responded to the scene after federal authorities notified them they had detained one person on an active criminal warrant there. The police arrested the person, a forty-six-year-old man. “To be clear, the Chicago Police Department only responded to the scene for criminal enforcement related to the offender’s active criminal warrant,” the statement said. “We did not participate in or assist with any immigration enforcement.” It added that CPD acts “in accordance with…the Welcoming City Ordinance.”

As Watson questioned agents about warrants and the legality of their raid, neighbors pleaded with her to be quiet for her own safety. She refused to back down.

“You claim you have warrants, but do you have a warrant to seize the entire building?” she asked the agents. “Do you have warrants to detain the entire building?” According to Watson, two federal agents told her that they were taking all detainees’ photos to check them against databases for visas or warrants.

When Watson walked around the block to capture footage of the ongoing raid, she noticed federal agents were using the parking lots of Excel South Shore Academy—a CPS contractor school— to load residents into vans. In them, Watson saw Black U.S. citizens, women, and children. Grabbed from their beds, they hadn’t been allowed to dress themselves before they were zip-tied and brought down to the waiting vans.

It’s Up to Us to Protect One Another

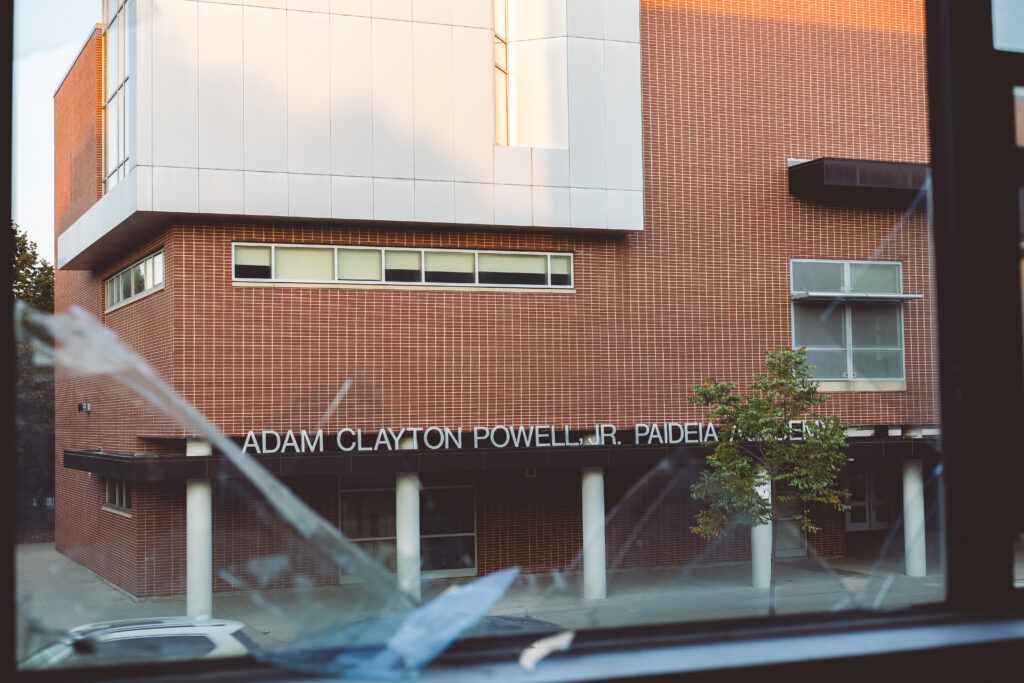

At Powell Elementary, located directly across the street from the raid, children share a similar fear. A source who requested anonymity because they work at Powell described the predominantly Black school as welcoming to new arrivals. While there are language barriers, he said the children support each other.

In the weeks leading up to the raid, the source and other employees saw what looked like federal agents parked in cars and trucks near the school. It made them worried about the students’ safety while walking home. Some kids have said they are “scared of walking home and getting grabbed on the way,” they said, adding that since the CPS Safe Passage program lost funding, the school only has one crossing guard on 75th Street.

They said that out of the seventy-five English language learner (ELL) students at the predominantly Black school, sixty were not in attendance the day after the raid. At least two students at the school lived in the building that was raided, and at the time of this reporting, the school has not been able to get in touch with them.

In a statement, a CPS spokesperson said the district does not share immigration status or cooperate with ICE. They did not, however, answer questions about attendance at Powell after the raid.

A letter the administration of Powell Elementary addressed to the community the day after the raid said, “as a reminder, our school and CPS WILL NOT coordinate with federal representatives, and we WILL NOT allow ICE agents or any other federal representatives access to our school unless they produce a criminal judicial warrant signed by a federal judge.”

Board of Education Member Yesenia Lopez (Dist. 7B) told the Weekly that while contracted option schools like Excel come up with their own policies outside of CPS, she would be following up to find out the status of charter and option schools’ policies regarding ICE.

Castro, of ICIRR, encourages families to make “preparedness packets” to leave behind if they’re detained, including instructions for guardianship and power of attorney if they have children, and a Department of Homeland Security privacy waiver (“ICE Form 60-001”) which allows someone to make a congressional inquiry to locate them within the detention system on their behalf.

Since the raid, Watson said she and her neighbors have only seen a few people return to the apartment building at 7500 South Shore. She said she thinks the Black people who didn’t have warrants were released, but she’s seen very few immigrants. Castro said she has heard that a couple of people were released on ankle monitors. “They went back to the building, but it was already boarded up.”

Block Club Chicago reported on Thursday that residents who were released were starting to return to the building and pick up the damage.

“The ones that are getting out are coming home to no home,” Watson said. According to her, after the raid occurred, building management stole or threw out residents belongings, including visas and important documents.

ICIRR is still trying to determine the identities of all the people detained in the raid. Castro said that the organization usually can do that by following up with family members or loved ones. “In this instance, there was nobody left to work with,” she said. The only detainee name they’re sure of is that of a person who passed their Venezuelan passport to a neighbor as they were being taken away.

By the end of last week, other high-profile incidents involving federal agents had knocked the raid at 7500 S. South Shore from headlines. Agents were seen choking a Black man on the West Side and conducted a raid outside a homeless shelter in Bronzeville on Wednesday. They shot and wounded a woman on Friday, hospitalized at least two people over the weekend, handcuffed a Chicago alderperson, and dispersed tear gas and pepper balls in confrontations with Chicagoans across the city all week.

“It’s not only affecting the immigrant community,” said Castro. “We are all at risk. [These federal agents are] making Chicago a more dangerous place.”

Everyone is scared, Watson said. “That [raid] gave so many people PTSD.”

She added that federal agents are no longer targeting only immigrants.

“No,” she said. “They are snatching up anybody.”

Maira Khwaja is a reporter and director of public strategy at the Invisible Institute. José Abonce is the senior program manager for the Chicago Neighborhood Policing Initiative and a freelance reporter who focuses on immigration, public safety, politics, and race.